The I Ching or Book of Changes (61 page)

2. Therefore the eight trigrams succeed one another by turns, as the firm and the yielding displace each other.

Here cyclic change is explained. It is a rotation of phenomena, each succeeding the other until the starting point is reached again. Examples are furnished by the course of the day and year, and by the phenomena that occur in the organic world during these cycles. Cyclic change, then, is recurrent change in the organic world, whereas sequent change means the progressive [nonrecurrent] change of phenomena produced by causality.

The firm and the yielding displace each other within the eight trigrams. Thus the firm is transformed, melts as it were, and becomes the yielding; the yielding changes, coalesces,

as it were, and becomes the firm. In this way the eight trigrams change from one into another in turn, and the regular alternation of phenomena within the year takes its course. But this is the case in all cycles, the life cycle included. What we know as day and night, summer and winter—this, in the life cycle, is life and death.

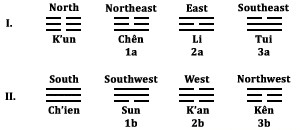

To make more intelligible the nature of cyclic change and the alternations of the trigrams produced by it, their sequence in the Primal Arrangement is shown once again [

fig. 3

]. There are two directions of movement, the one rightward, ascending, the other backward, descending. The former starts from the low point, K’un, the Receptive, earth; the latter starts from the high point, Ch’ien, the Creative, heaven.

Figure 3

3. Things are aroused by thunder and lightning; they are fertilized by wind and rain. Sun and moon follow their courses and it is now hot, now cold.

Here we have the sequence of the trigrams in the changing seasons of the year, and in such a way that each is the cause of the one next following. Deep in the womb of earth there stirs the creative force, Chên, the Arousing, symbolized by thunder. As this electrical force appears there are formed centers of activation that are then discharged in lightning. Lightning is Li, the Clinging, flame. Hence thunder is put before lightning. Thunder is, so to speak, the agent evoking the lightning; it is not merely the sounding thunder. Now the movement shifts; thunder’s opposite, Sun, the wind, sets in. The wind brings rain, K’an. Then there is a new shift. The trigrams Li and

K’an, formerly acting in their secondary forms as lightning and rain, now appear in their primary forms as sun and moon. In their cyclic movement they cause cold and heat. When the sun reaches the zenith, heat sets in, symbolized by the trigram of the southeast, Tui, the Joyous, the lake. When the moon is at its zenith in the sky, cold sets in, symbolized by the trigram of the northwest, Kên, the mountain, Keeping Still. Hence the sequence is (cf.

fig. 3

):

1a — 2a 1b — 2b

2a — 3a 2b — 3b

Thus 2

a

(Li) and 2

b

(K’an) are named twice, once in their secondary forms (lightning and rain), once in their primary forms (sun and moon).

4. The way of the Creative brings about the male.

The way of the Receptive brings about the female.

Here the beginning of sequent change appears, manifested in the succession of the generations, an onward-moving process that never returns to its starting point. This shows the extent to which the Book of Changes confines itself to life. For according to Western ideas, sequent change would be the realm in which causality operates mechanically; but the Book of Changes takes sequent change to be the succession of the generations, that is, still something organic.

The Creative, in so far as it enters as a principle into the phenomenon of life, is embodied in the male sex; the Receptive is embodied in the female sex. Thus the Creative in the lowest line of each of the sons (Chên, Li, Tui, in the Primal Arrangement), and the Receptive in the lowest line of each of the daughters (Sun, K’an, Kên, in the Primal Arrangement), is the sex determinant of the given trigram.

5. The Creative knows the great beginnings.

The Receptive completes the finished things.

Here the principles of the Creative and the Receptive are traced further. The Creative produces the invisible seeds of all development. At first these seeds are purely abstract, therefore with respect to them there can be no action nor acting upon; here it is knowledge that acts creatively. While

the Creative acts in the world of the invisible, with spirit and time for its field, the Receptive acts upon matter in space and brings material things to completion. Here the processes of generation and birth are traced back to their ultimate meta-physical meanings.

3

6. The Creative knows through the easy.

The Receptive can do things through the simple.

The nature of the Creative is movement. Through movement it unites with ease what is divided. In this way the Creative remains effortless, because it guides infinitesimal movements when things are smallest. Since the direction of movement is determined in the germinal stage of being, everything else develops quite effortlessly of itself, according to the law of its nature.

The nature of the Receptive is repose. Through repose the absolutely simple becomes possible in the spatial world. This simplicity, which arises out of pure receptivity, becomes the germ of all spatial diversity.

7. What is easy, is easy to know; what is simple, is easy to follow. He who is easy to know attains fealty. He who is easy to follow attains works. He who possesses attachment can endure for long; he who possesses works can become great. To endure is the disposition of the sage; greatness is the field of action of the sage.

This passage points out how the easy and the simple take effect in human life. What is easy is readily understood, and from this comes its power of suggestion. He whose ideas are clear and easily understood wins men’s adherence because he embodies love. In this way he becomes free of confusing conflicts and disharmonies. Since the inner movement is in harmony with the environment, it can take effect undisturbed and have long duration. This consistency and duration characterize the disposition of the sage.

It is exactly the same in the realm of action. Whatever is simple can easily be imitated. Consequently, others are ready to exert their energy in the same direction; everyone does gladly what is easy for him, because it is simple. The result is that energy is accumulated, and the simple develops quite naturally into the manifold. Thus it grows, and the sage’s mission to lead the multitude to the performance of great works is fulfilled.

8. By means of the easy and the simple we grasp the laws of the whole world. When the laws of the whole world are grasped, therein lies perfection.

Here we are shown how the fundamental principles demonstrated above are applied in the Book of Changes. The easy and the simple are symbolized by very slight changes in the individual lines. The divided lines become undivided lines as the result of an easy movement that joins their separated ends; undivided lines become divided ones by means of a simple division in the middle. Thus the laws of all processes of growth under heaven are depicted in these easy and simple changes, and thereby perfection is attained.

Hereby the nature of change is defined as change of the smallest parts. This is the fourth meaning of the Chinese word

I

—a connotation that has, it is true, only a loose connection with the meaning “change.”

CHAPTER II. On the Composition and the Use of the Book of Changes

1. The holy sages instituted the hexagrams, so that phenomena might be perceived therein. They appended the judgments, in order to indicate good fortune and misfortune.

The hexagrams of the Book of Changes are representations of earthly phenomena. In their interrelation they show the interrelation of events in the world. Thus the hexagrams were

representations of ideas. But these images or phenomena revealed only the actual; there still remained the problem of extracting counsel from them, in order to determine whether a line of action derived from the image was favorable or harmful, whether it should be adopted or avoided. To this extent the foundation of the Book of Changes was already in existence in the time of King Wên. The hexagrams were, so to speak, oracle pictures showing what event might be expected to occur under certain circumstances. King Wên and his son then added the interpretations; from these it could be ascertained whether the course of action indicated by the images augured good or ill. This marked the entrance of freedom of choice. From that time on one could see, in the representation of events, not only what might be expected to happen but also where it might lead. With the complex of events immediately before one in image form, one could follow the courses that promised good fortune and avoid those that promised misfortune, before the train of events had actually begun.

2. As the firm and the yielding lines displace one another, change and transformation arise.

This brings out specifically the degree to which events in the world are represented in the Book of Changes. The hexagrams are made up of firm and yielding lines. Under certain conditions the firm and the yielding lines change: the firm lines are transformed and softened, the yielding lines change and become firm. Thus we have a reproduction of the alternation in world phenomena.

3. Therefore good fortune and misfortune are the images of gain and loss; remorse and humiliation are the images of sorrow and forethought.

When the trend of an action is in harmony with the laws of the universe, it leads to attainment of the desired goal; this is expressed in the appended phrase “Good fortune.” If the trend is in opposition to the laws of the universe, it necessarily leads to loss; this is indicated by the judgment “Misfortune.” There are also trends that do not lead directly to a goal but are rather what might be called deviations in direction. However, if a

trend has been wrong, and we feel sorrow in time, we can avoid misfortune; if we turn back, we can still achieve good fortune. This situation is indicated by the judgment “Remorse.” This judgment, then, contains an exhortation to feel sorrow and turn back. On the other hand, a given trend may have been right at the start, but one may become indifferent and arrogant, and heedlessly slip from good fortune into misfortune. This is indicated by the judgment “Humiliation.” This judgment, then, contains an admonition to exercise forethought, to check oneself when on the wrong path and turn back to good fortune.

4. Change and transformation are images of progress and retrogression. The firm and the yielding are images of day and night. The movements of the six lines contain the ways of the three primal powers.

Change is the conversion of a yielding line into a firm one. This means progress. Transformation is the conversion of a firm line into a yielding one. This means retrogression. The firm lines are representations of light; the yielding lines, of darkness.

1

The six lines of each hexagram are divided among the three primal powers, heaven, earth, and man. The two lower places are those of the earth, the two middle places belong to man, and the two upper ones to heaven. This section shows the extent to which the content of the Book of Changes reproduces the conditions of the world.

5. Therefore it is the order of the Changes that the superior man devotes himself to and that he attains tranquility by. It is the judgments on the individual lines that the superior man takes pleasure in and that he ponders on.

From this point on we are shown the correct use of the Book of Changes. For the very reason that the Book of Changes is a reproduction of all existing conditions—with its appended

judgments indicating the right course of action—it becomes our task to shape our lives according to these ideas, so that life in its turn becomes a reproduction of this law of change. This is not the kind of idealism that artificially imposes an inflexible abstract pattern on a life of quite different mold. On the contrary, the Book of Changes embraces the essential meaning of the various situations of life: thus we are in position to shape our lives meaningfully, by acting in accordance with order and sequence, and doing in each case what the situation requires. In this way we are equal to every situation, because we accept its meaning without resistance, and so we attain peace of soul. Thus our actions are set in order, and the mind also is satisfied, for when we meditate upon the judgments on the individual lines, we intuitively perceive the interrelationships in the world.

6. Therefore the superior man contemplates these images in times of rest and meditates on the judgments. When he undertakes something, he contemplates the changes and ponders on the oracles. Therefore he is blessed by heaven. “Good fortune. Nothing that does not further.”

Here times of rest and of action are mentioned. During times of rest, experience and wisdom are obtained by meditation on the images and judgments of the book. During times of action we consult the oracle through the medium of the changes arising in the hexagrams as a result of manipulation of the yarrow stalks, and follow according to indication the counsels for action thus supplied.