The Incredible Human Journey (10 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

Good. That all seems to stack up quite nicely. Things get a bit tough in Africa about 80,000 years ago, with unpredictable weather patterns setting in. And then, from about 75,000 years ago, we see humans rising to the challenge, engaging their anatomically modern brains to invent new ways of life, better ways of hunting, and discovering their artistic talents.

Then, in the late nineties, someone came up with the idea of building a golf course at Pinnacle Point, close to Mossel Bay on the west coast of South Africa. The setting was stunning: a dramatic rocky coastline with native fynbos covering the tops of the cliffs. Fynbos is South African coastal heathland: a hugely diverse mix of proteas, heathers and reeds. But as well as its natural beauty, Pinnacle Point held archaeological treasures. For a long time, archaeologists had known that the caves there were used during the Stone Age, but it was not until a detailed survey of the caves was carried out, in preparation for the golf course development, that the wealth of material preserved in the caves was fully recognised.

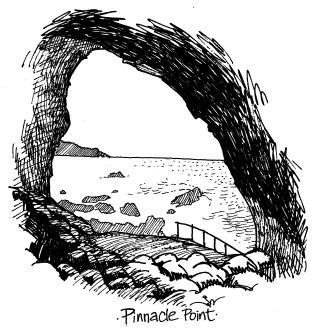

I drove up the garden route from Cape Town to Mossel Bay to meet archaeologist Kyle Brown, who had worked – and was still working – in the caves along this spectacular coastline. We met at the golf course clubhouse and headed for the cliff edge, descending a steep set of wooden steps to the rocky foot of the cliffs. Golfers practising their swings watched us with an air of curiosity as we disappeared over the edge. At the bottom of the steps, part of the wooden walkway had been smashed up in recent storms, and we had to jump down and scramble over the rocks. Kyle explained that there were twenty-nine archaeological sites along this short stretch of coast, at least eighteen of which were caves. Climbing up more steep steps, we eventually arrived at a large, teardrop-shaped cave entrance. ‘This is Cave 13B,’ said Kyle. ‘The very first place we excavated.’

I stood in the cave and looked out at a beautiful view, rolling waves crashing on to yellow-brown rocks. It was September and two whales were swimming very close to the coast. I could see their flippers raised in the air as they rolled over, and the jets from their blowholes. The cave seemed welcoming and homely; I could imagine camping out there. Kyle said it was a great location for protection from the elements on this stormy coast. He had worked here in all weathers and found that it provided excellent shelter from rain and prevailing winds.

Once the potential of this coast had been recognised, archaeologists started a long-term project, aimed at investigating the MSA archaeological record in the caves and tying this in with palaeoclimate data. The project was directed by Curtis Marean, of Arizona State University, and Peter Nilssen, of Iziko South African Museums.

7

The caves had originally formed about a million years ago, in quartzite cliffs. But there were also layers of limestone higher up in the cliffs, which dissolved and then percolated down through other layers, cementing them and forming breccia. ‘At different times in the past, some of these caves were open, whereas others were sealed off by huge sand dunes blown up the cliffs,’ Kyle explained. Breccia would form inside the sealed caves, and Kyle told me that the climate record contained in these layers amounted to an almost unbroken sequence for the last 400,000 years (apart from what he called a ‘short’ 5000-year gap). But at any one time,

some

caves would be open and available for human occupation. The limestone-impregnated breccia layers in the caves were important not only for dating and climate reconstruction, but also because they sealed in earlier archaeological remains and stopped them being washed away. This meant that Pinnacle Point provided a unique, long view: a record of both climatic and archaeological evidence, in one place.

The floor of the cave was covered in sandbags, to protect the archaeology. On one side, Kyle removed some sandbags to show me a small, excavated area. I touched the section: it looked like silt but it was rock-hard breccia. ‘This stuff is part of the reason we have the archaeology so well preserved,’ said Kyle. ‘It’s been cemented by flowstone that has come down the cave wall.’

‘Presumably you can’t dig this with a trowel?’ I asked.

‘No – it’s all dental picks and hand drills; it’s very, very difficult stuff to dig. This small pit took about four excavation seasons to dig. But it was well worth the effort.’

The lowest layer was the least cemented, and still quite sandy. It contained streaks of burnt material, possibly ancient hearths, as well as lithics and animal bones. Optically stimulated luminescence (or OSL) dating of this layer placed it at around 164,000 years ago. At that time, during OIS 6, the sea level was somewhat lower than today: the cliffs would not have been on the coast, but set back some 5 to 10km from it. Above those very ancient sediments was a layer containing hearths, but with fewer artefacts, dating to about 132,000 years ago. Sitting on top of that was a heavily cemented layer containing another layer of shells dating to about 120,000 years, and topped off with cemented dune sand and flowstone that had sealed the cave, and kept all that archaeology intact, building up from between 90,000 and 40,000 years ago. ‘These are some of the oldest archaeological deposits associated with early modern humans,’ said Kyle, quite proudly.

Kyle brought out a selection of stone tools that had been discovered in the excavations. ‘These are very typical of the stone tools we find in this cave: blades and points made of quartzite, locally available on the beach down here. And alongside those larger tools, we find these very small bladelets.’ They were indeed tiny, less than 1cm in width and perhaps 2cm long.

The stone tools from Pinnacle Point are a mixed bag of MSA and bladelets – like Howiesons Poort. In fact, more than half of the stone tools from Pinnacle Point are bladelets.

7

It looked like these people were using composite tools. ‘It’s hard to see how these tiny blades would have been used without hafting them, setting them in a handle. So these suggest advanced tool-making techniques,’ said Kyle.

The shells found in the upper cemented layer are also interesting. They include all sorts of edible shellfish, types that still thrive along this rocky shore, including many brown mussels (

Perna perna

), limpets (

Patella spp.

) and giant periwinkles (

Turbo sarmaticus

). There was also a fragment of whale barnacle, which may have been scavenged from the skin of a beached whale.

Kyle told me that the giant periwinkles provided extra information about past climate. While the shells themselves were often quite smashed up, the operculum, or trap door of the periwinkles was usually very well preserved. He showed me some: they were like small, white, slightly domed buttons, with a spiral on the flat side, and easily visible growth layers. Sampling oxygen isotopes from these opercula gave the archaeologists an idea of the ocean temperature and more general climate at the time the sea snail had been alive. Before they started on the ancient shells, the archaeologists wanted to check their calculations comparing modern shells against recent climate records. For two years, they had collected giant periwinkles from the shore to study their opercula. And Kyle said that they were delicious.

It might seem unremarkable that these hunting and gathering ancestors of ours were eating shellfish. But this is the first example of

any

human species exploiting marine resources. For millions of years, australopithecines and earlier

Homo

species had been restricted to eating land plants and animals. But it seemed that

Homo sapiens

developed a taste for fish and shellfish: exploitation of coastal resources is seen as another type of definitively

modern human

behaviour. From the evidence from other South African sites, it had been thought that this adaptation to coastal living came along perhaps 70,000 years ago. Archaeologists had argued that this development set the stage for the coastal expansion of modern humans out of Africa and into Asia. But once again, Pinnacle Point pushed the dates back – this time to about 120,000 years ago. Marean and his team suggested, based on the Pinnacle Point evidence, that shellfish may have become an important food source during OIS 6. During this glacial period, between 190,000 and 130,000 years ago, the environment became terribly dry, and humans would have struggled to find food. Turning to the resources on the coast may have been crucial to the survival of those early hunter-gatherers.

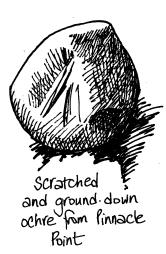

But the evidence for modern behaviour at Pinnacle Point didn’t stop there. In the lowest layer of the excavation, the archaeologists also found lots of pieces of red ochre: fifty-seven in total. And these weren’t just natural pebbles. They had been scratched and scraped. Kyle handed me one of the pieces of ochre that had been found in the cave. It was clearly faceted where it had been ground down, and scratched on one side. I had seen photographs of the ochre pieces, but it was so much more convincing when I held one and looked at it. There was no way that the marks and shaping of this lump of pigment could have happened naturally. So there it was, sitting in my hand, the earliest evidence for pigment use in the world: 164,000 years ago, the people of Pinnacle Point had been painting

something

.

‘We really have very little to go on,’ said Kyle. ‘But this ochre is our best evidence that these people were practising some kind of symbolic communication.’ The red ochre from Pinnacle Point is certainly

suitable

for body painting, but we’ll never know for sure what it was – the cave walls, or some object, or themselves – that they were covering in this colour, or what it meant to them. But I couldn’t help thinking of the Kibish women with their braided hair, faces, necklaces and breasts painted in deep, rich, red ochre.

Mellars

6

cautions against assuming that South Africa was where modern human behaviour appeared, because the preponderance of sites may simply reflect the fact that extensive investigation has been carried out there. And in fact there are similar sites in Tanzania and Kenya, although the dating of these has proved problematic. As we have seen, it is difficult to know exactly when our ancestors became, anatomically, modern human – but we know they had pretty much ‘got there’ by the time of the Omo fossils, 195,000 years ago. The genetic evidence also suggests an origin of our species around 200,000 years ago.

The evidence emerging from Pinnacle Point pushes back the date for the emergence of modern behaviour much closer to the earliest dates we have for the emergence of modern human anatomy.

7

Like the anatomical features, it is likely that behavioural traits we consider as modern appeared one by one, gradually coming together to form a mosaic, a ‘package’ of modern features. But what Pinnacle Point shows is that by 160,000 to 120,000 years ago the people living there had a fairly comprehensive portfolio of dietary (shellfish), technological (bladelets) and cultural (pigment use) behaviours that all shout out ‘modern!’.

The First Exodus: Skhul, Israel

It is difficult to trace population expansions within Africa: there has been a great deal of time for populations to move around, over several glacial cycles. Both archaeological and genetic investigation have been biased towards more developed and politically stable countries, meaning that there is very little evidence about early modern humans across great swathes of Africa. Nevertheless, genetic studies provide clues about the geographic origins of modern human populations in Africa. The most ancient mitochondrial lineage, L1, is found in the Bushmen of South Africa and the Biaka pygmies from the Central African Republic. The most ancient Y chromosome haplogroup is found in East Africa, among Sudanese and Ethiopians, as well as among the Bushmen and other Khoisan populations. Genetic lineages appear to have expanded from East Africa to the south and north, as well as out of Africa. African genes also record a much later expansion, of Bantu speakers, from a homeland in West Africa, towards the east and the south, some 3000 years ago.

1