The Incredible Human Journey (9 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

I sat down at the base of the slope and consulted the GPS. Following winding paths through the bush, the guides had brought me to almost exactly the place described by the coordinates I had been given. This was the place where Richard Leakey’s research expedition had turned up the earliest fossil remains of our species.

3

According to my GPS I was sitting very close to the findspot of the more complete Omo II skull. The other skull, Omo I, had been discovered in the same layer of sediment, but on the east side of the river.

The revisit to the site by Ian McDougall’s team was extremely important in producing the new, and very ancient, dates for the Omo fossils, but also in confirming that the two skulls came from the same layer. This was interesting, because the skulls are quite different shapes. Omo I is anatomically modern, through and through, if a little more robust than many modern skulls.

4

The braincase is globular, with the broadest point high up on the parietal bones, rather than low down, around the ears, as on earlier, archaic human skulls. It has a prominent browridge, but this thins out at the sides. The shape and size of the teeth and the prominence of the chin also mark it as modern.

5

But Omo II, was a bit odd-looking.

Sitting on that silty ridge near the Omo River, I pulled a cast of the Omo II cranium out of my bag. The face was missing, but most of the braincase was there. The sutures (joints between the plates of the skull) were practically closed, which suggested that its owner was adult, and getting on a bit. It was modern in some ways: in its round head, slight browridge and steep forehead. The volume of the braincase has been estimated as a very respectable 1435ml. But it also had an angled occiput (back of head) with a very marked horizontal ridge, or ‘occipital torus’, for the attachment of neck muscles, and a very slight ridge along the midline, called ‘sagittal keeling’.

4

These were archaic features: they are things that

Homo erectus

and

heidelbergensis

had as a matter of course, but they are features that have disappeared from modern populations today. Michael Day, the physical anthropologist who wrote the first report on the Omo skulls in 1969, noted that Omo II was more ‘archaic’ but classified both skulls as modern human,

Homo

sapiens

.

4

When Michael Day and Chris Stringer reassessed the skulls in 1991, they again drew attention to the more archaic-looking features of Omo II.

6

It’s a skull that may be best described as ‘on its way’ to being modern human.

That the earliest fossils of modern humans we have show some archaic features is not really surprising. It would be more remarkable if there was a sudden, global change in skull shape with the arrival of modern humans. Evolution proceeds gradually, step by step, and species change slowly over time (although, of course, each change relates to a mutation in a gene, which may have quite widespread effects on body shape and size). Looking at living species today, there are usually very clear morphological species distinctions. But when you are looking at species over time, it’s quite difficult to pin down when speciation ‘happens’, in other words when enough changes have occurred for the descendant population to be called a new species. Pinning a specific date on the emergence of a new species may be futile, because those gradual changes accumulate over time.

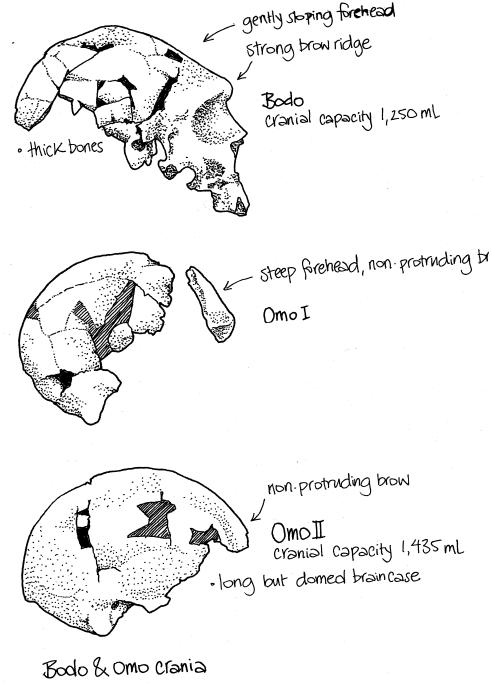

Between 600,000 and 300,000 years ago there was an earlier human species,

Homo heidelbergensis

, in Africa, represented by fossils such as the Bodo cranium from Ethiopia, and Kabwe (Broken Hill) from Zambia. This species seemed to combine some archaic features (similar to those seen in the even earlier species,

Homo erectus

) with some more anatomically modern features.

By 195,000 years ago we had the anatomically modern Omo skulls, the first of many:

Homo sapiens

was firmly on the map, and

Homo

heidelbergensis

was no more. It is wrong to see this as an extinction, though. The descendants of

Homo heidelbergensis

were still alive: they were modern humans (and Neanderthals in Europe – but more of that in a later chapter). So, somewhere between Kabwe at 300,000 years ago and Omo at 195,000, there was speciation. But presumably it was gradual, for otherwise we have to imagine a pair of

Homo heidelbergensis

parents producing a baby that looked most unlike them: a little anatomically modern human. So it is to be expected that the earliest anatomical modern humans would retain some archaic features; some anthropologists have called them ‘archaic

Homo sapiens

’ to distinguish them from the later, more gracile, more ‘modern’ forms. They were certainly more chunky than most of us today.

Of course, being anatomically modern is one thing. Those early Omo people may have looked like us (albeit with a slightly angular occiput, or back of the head) but did they think and behave like us as well? The only way we can even begin to tackle this question is by looking for clues as to how these people lived, what they made and, from that, try to deduce behaviour and patterns of thought. But the Omo site contains nothing of these sorts of clues: it is purely palaeontological, rather than archaeological. The fossilised bones of our ancestors were preserved there, which is wonderful, but it leaves us wondering what they were

like

.

I stayed for a few days around Omo, and spent some time in the village of Kolcho, near Murele camp. This was a Karo village, and body-painting was a strong tradition for this tribe. The first day I visited I met a young man called Muda whose torso was completely covered in white, finger-painted spirals. He spoke some English, and I asked if the painting symbolised anything. He was doubtful about any messages in the design itself, but said that men and boys had their bodies painted, while women and girls had their faces painted.

In the village a group of women sitting under a low, loosely thatched shelter invited me to sit with them. A couple of children were too, watching the women sewing. One girl was painting another’s face, and, when she was done, she started on mine. She had a small tin pot with white clay in it, and she used the round, blunt end of a nail to apply white spots on my face. Each one was like a little spot of coolness on my hot face. I found out that the little girl was called Buna. She introduced me to the other women and the growing crowd of children who were gathering to see the white-faced woman getting Karo spots painted on her face.

Buna was applying the spots in a careful pattern, leaving a wide circle around my eyes clear. Another little girl came to help, and Buna directed her. Eventually, Buna put the nail and the pot down and looked at my face, very seriously, then pronounced me done.

Muda reappeared and took me off to meet one of his friends. He stooped down at the doorway of a low, thatched hut, and I could see a woman inside. She invited us in, and we crouched down and entered her house. She was kneeling on the floor, roasting coffee, and Muda and I sat down opposite her. ‘My friend: Chowli,’ said Muda, in slow and careful English. Chowli was dressed the same way as all the other women in the village, in an apron-like soft leather skirt, which hung down low to the knees in front and behind, tied at the sides. She wore masses of bead necklaces, and her forearms were stacked with brass bangles. Buna followed us in and sat by me: I discovered that Chowli was her mother. Through Muda’s little bit of English, we managed to have a weird kind of conversation; I don’t think any of us really knew what it was about. But Chowli did indicate that she was impressed by Buna’s work on my face.

The smell of the roasting coffee was fragrant in the air; Chowli lifted the pan off the fire and emptied the coffee into a half-gourd and poured in hot water. Then she handed it to me to taste. I lifted it to my lips with great reservation: I had been

so

careful about what I ate and drank in Omo, and now it was all about to go to pot. I knew, as I took a sip, that I was risking vomiting and diarrhoea later that evening. (Thankfully, I escaped unscathed. And it was good coffee.) Before I left, I gave them some cereal bars, and Chowli passed over one of her brass bracelets, which Muda opened into a wide ‘C’ and then closed around my wrist. ‘Friends,’ he said, gesturing between us. Not to be left out, Buna gave me a yellow and blue bead bracelet.

As well as visiting the Omo fossil site, and feeling utterly in awe at just being in a place that we can truly call the birthplace of humanity, I would also treasure experiences like meeting Muda, Buna and Chowli. And writing about it makes me think again about how those ancient Omo people might have been. If I was able to travel back in time, would the original tribespeople invite me in for coffee? Would they understand friendship? These are philosophically interesting, but ultimately unanswerable questions (although I suspect coffee drinking may be a somewhat later cultural development). But there are other aspects of humanity that archaeologists

can

expect to find traces of, and one of them is the urge to decorate: to paint and adorn ourselves and our environment. There was an explosion of art – including cave art, figurines and beads – from around 30,000 to 35,000 years ago in Europe, but there are traces of art and adornment going back much, much further than that. And I think that art, like music and language, implies a level and quality of consciousness that we can call ‘modern human’.

Modern Human Behaviour: Pinnacle Point, South Africa

I left Omo and headed south. There are a number of quite famous Middle Palaeolithic sites in South Africa, where evidence of what looks like modern human behaviour has been found, including Blombos Cave, Klasies River Mouth, Boomplaas and Diepkloof.

Although these sites are broadly classified as Middle Stone Age, there are particular technological and cultural features that make them stand out from older MSA sites. In other words, the archaeologists argue that while the sites may be MSA, they are MSA with signs of

modern human

behaviour. (This is an important distinction to make because earlier species like

Homo heidelbergensis

also made MSA tools, and in the last decade of the twentieth century many archaeologists still believed that humans didn’t become ‘fully modern’ until 45,000 years ago.)

1

The ‘modern’ features from these South African sites, dating to between 55,000 and 75,000 years ago (well before the colonisation of Europe and the Upper Palaeolithic), include a new way of flaking bone, using a soft hammer (perhaps bone or antler), specialised end-scraper tools that archaeologists believe were used for cleaning hides, and pointy burins – presumably for making holes in leather or wood. The assemblages also included the first bone tools, including things that may be spear points and awls. There are also tiny stone flakes, which may have been used as inserts in spears to make them harpoon-like, or perhaps even as arrowheads (though there is no definite evidence of bow and arrow technology until much, much later – about 11,000 years ago). Small pieces of stone may not sound impressive or important, but they suggest that people were making composite weapons: similar to the type of technology that is seen, much later, in the Upper Palaeolithic of Europe and Asia. And even if the tiny blades aren’t evidence of archery, they do at least seem to suggest that new, more effective hunting tools were being developed. From the original source of the stone material used, it seems that there was some fairly long-distance trading going on, perhaps indicating widening and increasing complexity of social networks. The presence of tiny bladelets within an African MSA assemblage was first noticed in a site in South Africa called Howiesons Poort.

2

Similar toolkits have also been found in East Africa, at the site of Mumba in Tanzania, and at Norikiushin and Enkapune ya Muto in Kenya.

3

But as well as these technological advances, sites in South Africa have also produced tantalising suggestions of early art and ornamentation. In Blombos Cave, archaeologists found pierced sea snail shells; careful inspection of the holes in them showed that these perforations were not natural, and experiments on shell with a sharp bone point produced similar results. The edges of the holes and the lip of the shells were slightly worn down, showing they had been strung and worn.

4

Numerous pieces of ochre had been transported into the cave at Blombos, including some lumps with geometric patterns scratched on to them, dating to around 75,000 years ago. These engraved ochre pieces have been held up as the earliest examples of ‘abstract art’.

5

,

6

Archaeologists have linked these technological and cultural developments to environmental changes happening between 80,000 and 70,000 years ago. This was the time of the transition between the warm interglacial known as OIS 5 to the chilly glacial OIS 4, and that change was marked by dramatic swings between wetter and drier conditions. The eruption of the Toba super-volcano 74,000 years ago may have destabilised the global climate as well. So perhaps it was these environmental challenges that drove the invention of new technologies, the expansion of social networks and somehow produced a need to mark identity, and even communicate, through the use of art and ornamentation.

6