The Incredible Human Journey (4 page)

Read The Incredible Human Journey Online

Authors: Alice Roberts

If the effect of a mutated gene is deleterious, it may be that the individual carrying it won’t be able to survive at all,

or, perhaps, won’t live long enough to pass their genes on. So the mutant gene will disappear from the mix of genes in the

population, or ‘gene pool’. If the product of a mutant gene proves advantageous, it could be that the individual with it gains

a better chance of survival, and is therefore very likely to pass the new version of that gene on to their offspring. So,

gradually, over many generations, a really advantageous gene can spread through a population.

If the mutation is neutral, then it is pure chance whether it sticks around or disappears from the gene pool.

But there are also long stretches of our DNA that mean nothing to the cell; they are the bits between genes which are never

‘read’ to produce proteins. Sometimes they contain parts of old, disused genes, or historical bits of genetic material inserted

into the chromosomes by viruses. These unused sections are not subject to natural selection like the working genes. Alterations

appearing by random mutations in these regions will not be weeded out in the same way. This means that they are quite useful

for tracing genetic lineages.

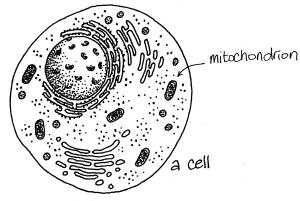

Most of our DNA is coiled up in chromosomes inside the nuclei of our cells; there is also a little bit of DNA in tiny capsules

inside the cell. These are mitochondria, the tiny ‘power stations’ of the cell, taking fuel – sugar – and burning it to produce energy. The

genes in the mitochondrial DNA have a very specific but incredibly important job, controlling energy transformation inside

the cell. To a large extent, because they’re so hidden away, they too are protected from pruning by the grim reaper of natural

selection. Mutations accumulate more rapidly in mtDNA than in the nuclear DNA.

17

So this means that mtDNA is particularly useful for reconstructing genetic family trees. Geneticists can assume that there

is a standard rate of mutation within the mitochondrial DNA, and that, unless they really hamper the work of the mitochondria,

those mutations will persist.

The other important thing about mitochondrial DNA is that it does not get mixed up at each generation like the nuclear genes. Gametes (eggs and sperm) contain only half the number of chromosomes contained in every other cell

in your body. But when the sperm and the egg are first made, it’s not simply a question of dividing the pairs of chromosomes

up – before that happens, each pair of chromosomes swaps DNA with its partner, in a process called recombination. That means that the

twenty-three chromosomes left in the gamete contain new mixes of DNA that weren’t there in the father or mother.

Sexual reproduction – with this shuffling of genes at each generation – means that genetically ‘new’ and different individuals

keep being created. This in turn creates variability within the gene pool. This variation is incredibly important: it means

that, if circumstances change, if the environment changes around us, there will be some individuals who may be able to survive

better than others. Biology cannot predict what changes may be needed at some far-off point in the future, but species that

have developed this way of ‘future-proofing’ themselves, through sexual reproduction, have been successful in the past –

and so we still do it today. But for geneticists trying to trace genes back through generations, it is a nightmare, because

the genes keep jumping about.

Mitochondrial DNA, on the other hand, does not get involved in recombination, and stays, chaste and untouched, inside the

mitochondria – which we all inherit from our mothers. The sperm from our father contributes just its nucleus with twenty-three

chromosomes at fertilisation. The egg also contains twenty-three chromosomes, as well as all the other cellular machinery – including mitochondria. This

means that all your mitochondria, and the DNA they contain, are inherited from your mother. And she got hers from her mother, and so on. Geneticists can therefore trace back maternal lineages using mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA). Of the nuclear DNA in our chromosomes, there is actually one bit that doesn’t recombine, and that is part of the

Y chromosome (which only men have). So this can be used to trace back paternal lineages.

In fact, other genes, in the nuclear DNA,

can

be traced back, although the history of these genes is more convoluted and much harder to track back through time than the

non-recombining bit of the Y chromosome or mtDNA. Techniques for analysing DNA, for reading the sequence of nucleotide building

blocks, are getting better and faster, almost by the day. Many labs are not looking at just individual genes from mtDNA or

nuclear DNA but are now attempting to read

all

the DNA – mapping entire mitochondrial and even nuclear genomes. It’s an exciting time.

In terms of investigating our ancestry, it’s those tiny differences in our DNA, nuclear or mitochondrial, that are important.

The traditional approach to studying genetic variation was ‘population genetics’, where frequencies of different gene types

are compared between different populations. The problem with this approach is that it is particularly subject to distortions,

as people migrate and populations mix. The approach of building ‘family trees’ of genes, from mtDNA, the Y chromosome and

other nuclear DNA, makes for a much clearer picture of our inter-relatedness and our ancestry. The branch points of the trees

correspond with the appearance of specific mutations.

18

There are obviously ethical issues involved in the collecting of DNA: it should be done only with the consent of the individual concerned, it should be used only for the purposes initially laid

out, and should not be passed on to any third parties. Some people have worried that genetic analyses of human variation might

be used for a racist agenda, but these fears can be allayed as this science actually contains a strong anti-racist message.

As eminent geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza has put it: ‘Studies of human population genetics and evolution have generated

the strongest proof that there is no scientific basis for racism, with the demonstration that human genetic diversity between

populations is small, and perhaps entirely the result of climatic adaptation and random [genetic] drift’.

18

The Illusion of the Journey and the Folly of Hero-Worship

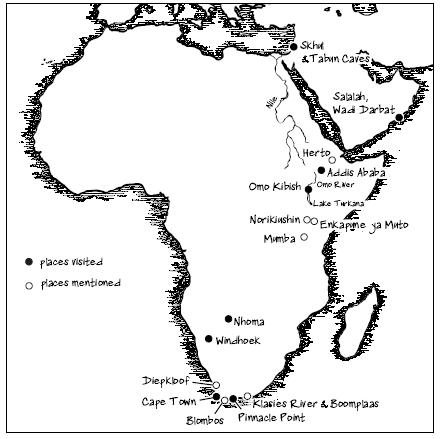

This book is about several different sorts of journey. There are the physical journeys made by our ancestors as they spread

around the world. Then there is a more abstract, philosophical journey, with the gradual transformation of body and mind to something we can

recognise as fully modern human. And then, there is my own physical and mental journey. I spent six months travelling around the world, meeting all sorts of experts and indigenous people, and experiencing the huge

range of environments that humans manage to survive in today, from the frozen taiga of Siberia to the blazing aridity of the

Kalahari.

When we cast our minds back and imagine our ancestors, sometimes surviving against the odds, and managing to make their way

into and survive in the most extreme environments, it may inspire us with humility, awe and great admiration. And it certainly

is

an awe-inspiring story: from the origin of our species in Africa, to the colonisation of the globe.

But it’s all too easy to start thinking of this journey as a heroic struggle against adversity, and to imagine our ancestors

setting out with the explicit intention of colonising the world. In fact, this ‘human journey’ is a metaphor – as it wasn’t

really a journey at all – and they had no such goal in mind. I think that words like ‘journey’ and ‘migration’ are useful

metaphors for describing how populations have moved across the face of the earth over vast stretches of time, but it’s very

important to realise that our ancestors were

not

on some kind of quest to get on and colonise the world. Certainly, they were nomadic and they would have moved around the

landscape as the seasons changed, but most of the time they would not have been purposefully moving on from one place to another.

It’s just that, as populations (of humans or other animals) expand, they spread out. But I think it’s acceptable to use words

like journey and migration to mean something more abstract, a diaspora happening over thousands of years. So there was no

quest, and no heroes. We may feel humbled by the survival of our species, though set about by vicissitudes, and we may marvel

at our ancestors’ ingenuity and adaptability – but we must remember, through it all, that they were just

people

– like you and me.

Meeting Modern-Day Hunter-Gatherers: Nhoma, Namibia

I was sitting at a wooden table, under a thatched roof, somewhere out in the bush, in Namibia. A small but noisy flock of

grey louries was flying about in the trees around the camp, calling ‘go-away!’ loudly. Beyond, the landscape of scrub and grassland stretched off, unbroken, into the distance. I was excited about being in Africa: it was the starting point of my journey and where the story of the human colonisation of the world begins.

I had flown into Windhoek and from there taken a small plane to fly out into the Kalahari Desert. We approached our destination, somewhere on the northern edge of the Nyae Nyae conservancy area, and circled, looking for the landing strip: a bare patch of dusty ground in the middle of the bush.

We landed, kicking up great clouds of dust and sending the crowd of inquisitive children that had gathered at the end of the airstrip running, screaming away. They returned to watch as we taxied, came to a halt, leapt out and started to unload. A few of the boys were holding long, straight sticks, and they were trimming off side twigs and whittling them down with knives.

It was extremely hot and very dry. Small trees and bushes were dotted about, with swathes of pale golden grass between. It was a short drive to Nhoma, a Bushman village situated on a ridge looking out across this landscape. There was nothing else for miles around.

I got out at a lodge near the village, and met Arno Oostuysen, who introduced me to field guides Bertus (himself a Bushman) and Theo (a young South African spending a year at Nhoma). We walked through the bush on sandy paths into the village. There were shelters, about twenty of them, around the edges of a clearing. The shelters were simply built, with branches anchored in the sandy ground and bent in to form a dome shape, covered with sheafs of grass.

Theo said there were 110 people living in the village, and that they were mostly members of just two extended families. This was a ‘matrilocal’ society: men married out and went to live with other Bushman bands in neighbouring villages, while women stayed in the village of their birth. He took me to meet one of the older men of the village. The Bushmen do not have leaders as such, but this man had the hunting rights over the land around, and it was courteous to thank him for letting me visit.

These people looked completely different from the black Namibians I had seen in Windhoek. The Bushmen were short and very lightly built, and relatively pale-skinned. They had the tightest curls of black hair on their heads, and open, wide faces, with high cheekbones. I looked at some of their profiles, and, from the side, their faces were quite flat below the nose: they did not have the jutting jaws of other sub-Saharan Africans. They had very narrow shoulders and a very pronounced curve in the lumbar spine which placed the hips far back.

Some people were sitting in groups, gathered in the shade under the trees. One woman was making ostrich-shell beads. Having carefully chipped pieces of shell into tiny discs, she was now drilling holes into them. She had a plank of wood about half a metre long on the ground in front of her. She placed the shell discs into small holes worn into the wood by previous beads, then drilled them by twirling a long, pointed stick between her hands. She drilled into one side, then turned them over and drilled the other. The beads would then be polished before they were ready to be threaded into a necklace or bracelet.

I walked over to where three other women were sitting on colourful cloths spread out on the ground, piles of small glass beads between their legs. They were threading beads to form colourful bands which would make bracelets, necklaces and headdresses. Some of the women had rows of traditional small, black, linear scars on their thighs and faces. Children of various ages were sitting with them, watching the women at their beadwork. I sat down and watched. After a while I indicated that I’d like to try making something, and one of the women started me off, with two rows of yellow beads on a new length of thread, which she then handed over to me to continue. I was given my own small pile of beads and I got to work. It was very calm, almost meditative. Patterns started to emerge in the beadwork. More children came over to see what I was doing and to inspect my slowly growing band of beads. All the time, there were soft conversations going on, and every now and then the children would start up a song that would spread throughout the group. The words sounded very strange to me. There were sounds like vowels and consonants I was used to, but there were also clicks. Some words seemed to be almost entirely made up of clicks.

The language was one of the things that brought me here, to this isolated village in the Kalahari. Click languages are unique to populations in southern Africa and Tanzania – including the Bushmen (San) of Namibia and Botswana, and the Khoi Khoi (Khwe) of South Africa (sometimes these people are collectively referred to as Khoisan). Historically, these populations have had different lifestyles: the Bushmen being traditional foragers (i.e. hunter-gatherers) and the Khoi Khoi traditional herders.

1

Although their languages differ, they are bound together by these common sounds: characteristic clicks made by snapping the tongue away from the teeth or the hard palate. For many years anthropologists and linguists have suspected that the languages shared by these now widely separated tribes might indicate a very ancient, common ancestry.

2

After a while, one of the little girls spoke to me in English.

‘What is your name?’ she asked, carefully pronouncing the words. I told her, and asked what hers was. ‘Matay,’ she said.

I asked Matay the name of the woman who was teaching me beadwork. She was called ‘Tci!ko’ – pronounced ‘Jeeko’, with a click on the second consonant.

I took some of the coloured beads and laid them out on the cloth between us. ‘This is red … yellow … and green,’ I said. ‘What do you call them?’

Matay understood and tried to teach me the words for the three colours but I found it really difficult. There were clicks in the middle of words, sort of on top of other consonants as well. And not only that, but the clicks were not all the same!

An elderly woman – she must have been at least seventy – came over to see what I was doing. Her face was deeply lined and she had only a few teeth left. The other women and children treated her with great deference. She held out her hand and I gave her the fragment of beadwork I had made. She turned it over and inspected the threading carefully, then handed it back to, beaming with approval. The other women nodded and smiled as well. Although I felt quite isolated by my lack of understanding of the language, this was a form of communication that did not need words.

Later in the day I had a click-speaking lesson from Bertus. We sat on low wooden stools in the doorway of one of the shelters. Inside the hut, bags and clothes hung from wire hooks, and there were a few reeds with guinea-fowl feathers attached. (This was a traditional game called

djani

– or the ‘helicopter game’ – a winged toy, with a short thong-and-resin weight at the bottom. Thrown into the air, the reed would spiral down like a sycamore key, and the player would try to catch it with a long stick. One of the hunters later gave me a demonstration.)

Bertus explained that there were four clicks in Ju/’hoansi (pronounced something like ‘Voo–nwasee’, with a click in the middle). The Ju/’hoansi are a group of Bushmen living around the border between northern Namibia and Botswana.

3

They are the same group that anthropologists used to call ‘!Kung’. (Although the indigenous people of the Kalahari know themselves by their individual, tribal names (such as Ju/’hoansi), they are happy to be known collectively, and refer to themselves in English, as Bushmen. Fifty years ago, this was a term that many anthropologists avoided, as it was one given to those communities by the first European settlers and it was considered to be derogatory. Anthropologists therefore sought another, more acceptable term, and they settled for a word used by other southern Africans to describe the Bushmen: ‘San’. This word has become common but itself has derogatory overtones as it apparently means ‘cattle thief’.)

Bertus went through the four clicks, accentuating the shape of his mouth and repeating each of them so that I could see where he was placing his tongue in relation to his teeth and soft palate. So here they are:

1. / The dental click: made by placing the tip of the tongue against the front teeth then snapping it away. It’s like a tutting noise.

2. ≠‚ The alveolar click (I found this difficult because it sounded so similar to the first one, but the tongue is placed in a slightly different place: just behind, rather than against, the front teeth).

3. ! The alveolar-palatal click: the tongue is placed against the hard palate just where it starts to dome up – behind the ‘alveolar’ ridge. (For those who are interested,

alveolus

means ‘cup’, and so the word ‘alveolar’ applied to the upper and lower jaws refers to the part of the jaws that bears the cup-like sockets for the teeth.) When the tongue is pulled down quickly, it makes a loud ‘nop!’

4. // The lateral click: the tongue is positioned as for the second click, but only the side is released. ‘Like if you call a dog,’ said Bertus. To me, it sounded like a noise you might make to gee up a horse.

Genetic studies of people speaking click languages, looking at both mitochondrial DNA and the Y chromosome, have shown that the Ju/’hoansi have remained quite isolated from populations around them, while other Bushman groups and the Khwe people have mixed extensively with Bantu populations. The Ju/’hoansi have unique, deep-rooted genetic lineages. A recent study found that the branches leading to different groups of click-speaking people appeared very early in the family tree of modern humans. It’s impossible to prove, but geneticists suggest that click languages may have been around for tens of thousands of years, originating before any movement of people out of Africa.

1

For years anthropologists have debated whether or not the Ju/’hoansi have roots going back into the Later Stone Age, or perhaps even earlier, in the area that they still inhabit.

3

In the 1950s, anthropologist Lorna Marshall found that the Bushmen believed their ancestors to have lived in the region forever. The genetic lineages of the Bushmen suggest that they are indeed descendants of very ancient inhabitants of the area.

The children thought my attempts to speak Ju/’hoansi hilarious. There were plenty of children in the village, of all ages. And the older kids of nine or ten were looking after the toddlers; some were carrying tiny ones round in shawls tied to their backs. A few small boys were pushing round model cars, made of coat hanger wire, with such great attention to detail that some even had wire ‘treads’ on the wheels to make authentic tyre tracks, and grills on the front. One was unmistakably – in skeletal form – a Toyota Hilux. Theo said that each time a new vehicle arrived at the village it was only a couple of days before an accurate wire model of it appeared on the scene.

A few of the boys were playing a game on the edge of the village, with the thin sticks I had seen them whittling earlier, at the airstrip. They were throwing the sticks, hard, at a small grass-covered mound: the sticks ricocheted off and sped away like arrows. There didn’t seem to be any particular aim to the game, and no one was scoring, winning or losing. Theo said this was a way of doing things that permeated Bushman society: they were not competitive. Anthropologists visiting Bushmen communities remarked on the lack of inter-group violence as well.

2

Two men were sitting beside one shelter, attending to their hunting equipment. One had a small bowl of water with sinews soaking in it, and he was wrapping these shiny, silver ligaments around the ends of his bow, to help keep the string (also sinew) in place. The other hunter was inspecting his arrows, holding each one up and looking down the shaft to check that it was straight. They were composite arrows, with a shaft made of a thick grass stalk, and a detachable end or foreshaft. Theo explained that this was designed to break off from the rest of the shaft once the arrow had found its quarry; the remaining, shortened arrow would be less likely to get knocked out as the animal ran on. About 10cm of the shaft just behind the gleaming, beaten, steel wire arrowhead was covered in a black substance. Theo cautioned me not to touch it: it was poison. The hunters used the larvae of

Diamphidia

beetles to anoint their arrows with a deadly mixture. Hunting would involve tracking an animal until the hunters were close enough to fire poisoned arrows into it, then they would carry on, tracking it at leisure, until the quarry weakened from the poison and exhaustion and the hunters could approach it and deliver the

coup de grâce

. Theo introduced me to the hunters. They were brothers-in-law, !Kun and //ao, and they were going to take me out – right out – into the bush the following day.