The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex (32 page)

Read The Ins and Outs of Gay Sex Online

Authors: Stephen E. Goldstone

PSA, an enzyme manufactured only by prostate cells, liquefies those nice little clumps of semen after you ejaculate.

Some of it spills naturally into your blood (don’t worry, it won’t hurt you), and a blood test can measure the level.

Cancer cells generally produce much more PSA than normal cells, so blood levels rise in men with prostate cancer.

Your PSA level also increases from BPH, prostatitis, or after prostate biopsy or injury.

(Use your imagination.

) Normal PSA levels are less than 4 nanograms per milliliter.

The higher your PSA goes, the greater the likelihood that you have cancer.

Neither a rectal examination nor a PSA measurement is foolproof.

Each test misses cancers in some men and wrongly predicts them in others.

But together, they are our best tools for early diagnosis of prostate malignancies.

Currently the American Cancer Society recommends a yearly PSA and rectal examination in all men over age fifty.

For blacks and men with a close family history of prostate cancer (fathers, brothers, or grandfathers with the disease), the age for yearly screening is pushed back to forty.

Because the disease spreads so slowly, screening past the age of seventy is not recommended.

(In other words, if you’re over seventy and develop prostate cancer, you’ll probably die from some other cause.

)

If a doctor suspects a prostate tumor, you’ll need a transrectal ultrasound and needle biopsy.

A small lubricated probe inserted (painlessly) into your rectum bounces sound

waves into your prostate, making even the tiniest nodules visible.

The ultrasound picture guides the doctor’s insertion of a very skinny needle through your rectum into your prostate to obtain a cell sample.

These cells are then studied under a microscope to determine if indeed you have prostate cancer.

Ultrasound guided biopsy does not require hospitalization or anesthesia and often can be performed right in the doctor’s office.

If the initial attempt failed to diagnose a cancer, a still-suspicious doctor might advise an additional biopsy, because 15 percent of the time the first biopsy is negative while the second one finds cancer.

Early detection means the difference between a cure and certain death, so please don’t refuse a biopsy if your doctor advises.

Prostate cancer does not mean the end of the world.

When it is caught early, before it has spread, it is a curable disease.

Even when prostate cancer has spread, excellent treatment options can guarantee you a long life.

Doctors usually propose one of three different treatments for men with prostate cancer:

surgery, radiation therapy, or doing nothing at all.

I’m sure your eyebrows rose at the prospect of doing nothing:

How can a doctor just leave you with a cancer?

The answer is simple.

If your probable survival even without prostate cancer is limited (less than 10 years), no treatment may be the best treatment of all.

Radical surgery and radiation therapy are the best ways to cure prostate cancer.

A radical prostatectomy removes the entire gland and surrounding lymph nodes.

Nerves that control your erection run nearby.

In the past they were routinely cut out along with the tumor, leaving many men impotent.

Now surgeons try to save at least some of these nerves, so the chance of impotence for men under sixty is less than 50 percent.

Impotence after prostate surgery can be cured with medications or a penile prosthesis.

(See

Chapter 7

.

) Other frequent, troubling side effects of the surgery include no ejaculation (you still have an orgasm,

but nothing shoots out) and urinary incontinence (failure to control your urine).

Many men note mild stress incontinence (they dribble urine if they sneeze, cough, or bear down on abdominal muscles), but sanitary pads usually handle this problem.

Complete incontinence is a significant problem for less than 5 percent of men after radical prostatectomy.

Some may need surgery to correct it, while others wear a bag to catch leaking urine.

Many years after any type of prostate surgery men may develop a bladder stricture from scarring, which blocks urine flow.

Often a surgeon will dilate the stricture, which relieves the problem.

Occasionally, further surgery is necessary.

All in all, the prognosis for fifteen-year survival after radical prostatectomy for a localized cancer (one that didn’t spread) approaches 90 percent.

Radiation is another excellent treatment alternative for prostate cancer that has not spread, and its fifteen-year survival rates reach 85 percent.

Radiation therapy, spaced over seven weeks, kills cancer cells and can damage other structures in the beam’s path.

Accordingly, even though the treatment itself is painless, nerves controlling erections can be destroyed, leaving 50 percent of men impotent.

Because intestines, bladder, and rectum are often in the path of the radiation beam, patients undergoing radiation treatment can expect some indigestion with crampy pain, bowel irregularity, rectal bleeding, and painful, frequent bloody urination.

Sounds horrible, I know, but often these symptoms are mild, easily managed with medication, and they usually resolve or lessen once your treatment ends.

Less than 5 percent of men experience urinary incontinence after radiation therapy.

Which is better, radiation or surgery?

Radiation therapy has the significant advantage of not requiring surgery with all its attendant risks (bleeding, prolonged hospitalization, etc.

), but it does require a significant time commitment.

Although survival rates are fairly similar for early prostate cancer whether it’s treated surgically or with radiation, most doctors believe that in a relatively healthy man with a life expectancy of greater than ten years, a radical prostatectomy is preferred.

Surgical survival rates surpass radiation therapy as a man lives longer than ten years after treatment.

If faced with the frightening prospect of metastatic prostate cancer (cancer that has spread to other parts of your body), try to remember that all is not lost.

Although prostate cancer is relatively resistant to most common chemotherapy drugs, it is very sensitive to hormone therapy.

Prostate cells depend on testosterone to grow normally, and so do prostate cancer cells.

Even if cancer has spread, anything that decreases testosterone levels impedes its growth.

Castration is the obvious best method for lowering testosterone levels, and it is a safe and risk-free operation.

Fake testicles inserted into the scrotum feel like normal balls.

(If this is important to you, ask your doctor before the surgery.

) For most men, a surgical castration is too disturbing.

Instead they opt for medical castration, which is accomplished with various drugs.

The most common form of pharmacological castration is a class of drugs called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists (LHRH), a fancy name for something that basically tells your testicles not to make testosterone.

Leuprolide acetate (Lupron) or goserelin acetate (Zoladex) are administered via injection once a month.

Side effects are similar to castration—loss of libido and impotence.

Some men develop hot flashes and other menopause-type symptoms.

Initially, these medications can cause

increased

testosterone levels with worsening of the cancer.

To combat this, a doctor may add another antitestosterone medication (flutamide [Eulexin], nilutamide [Nilandron], or bicalutamide [Casodex]) for the first week or two of therapy.

After medical or surgical castration, most men go into

remission with either a regression of their cancer and/or a slowing of its progression.

Many times they can look forward to several years of good life.

Doctors are also testing cancer cells, looking for factors that predict whether the tumor will grow quickly or not.

More aggressive treatment might be indicated for men with fast-growing tumors, whereas doctors would be more inclined to just watch slow tumors.

If men develop urinary obstruction from prostate cancer, many doctors combine hormone therapy with a TURP (scraping) to open the urethra.

Radiation therapy is also beneficial when cancer has spread to bones and other organs.

Now for the second most favorite part of most men’s anatomy.

You may think of your scrotum as just a sac of wrinkled, thin skin, but it performs the complex function of regulating testicular temperature.

Just as women are taught to examine their breasts, men must learn the importance of regular scrotal checks—especially young men, who are at greatest risk for testicular cancers.

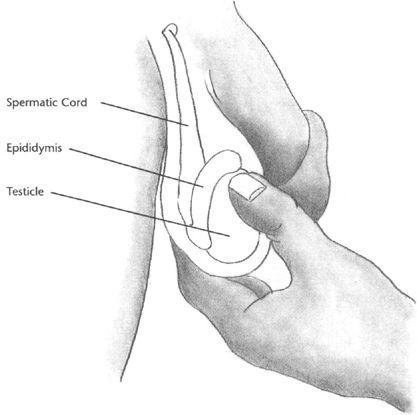

And your testicles aren’t the only structures your scrotum holds.

It also contains your spermatic cord with its many vessels that bring blood to and from your testicles.

Your epididymis, which is draped over the back of each testicle, is another important part of your scrotum.

(See

Chapter 6

.

)

Because your scrotum rises and falls to keep your testicles at exactly the right temperature, examine it when it is fully extended so you can feel its entire contents.

When pulled up tight, your epididymis and spermatic cord may be out of reach.

You may find it easier to examine your partner and for him to examine you—just don’t incorporate the exam into foreplay, because sexual stimulation draws the scrotum up, limiting your ability to feel individual structures.

Some doctors recommend examining your scrotum in a shower or bath, because hot water makes it as floppy as possible.

While that is certainly an option, it is difficult to see skin properly under water, and a visual inspection is an integral part of any examination.

Begin your examination with a visual inspection in a well-lighted setting.

Carefully spread your pubic hair so that you can see all areas.

Some men find shaving the hair from their scrotum a pleasurable experience as the razor glides over sensitive skin.

Just beware of nicks, which can become infected, or ingrown hair follicles.

Any swelling or redness after shaving needs warm compresses, frequent cleansing with antibacterial soap, and possibly even antibiotics.

As with any infection, don’t wait too long to see a physician.

When examining your scrotum, look for any

new

lumps, bumps, or blemishes.

Any skin disease you have elsewhere (psoriasis, fungal infections, moles, etc.

) can spread to your scrotum.

Because your scrotum is not normally smooth, it is important that you examine any skin abnormality for change.

A mole that you have had for years is not a problem unless it starts growing or darkens.

Beware of any STD—particularly warts and herpes, which can infect your scrotum and are easily overlooked.

Warts are often mistaken for skin tags, especially if you don’t have them anywhere else.

If in doubt, have your doctor check you out!

If you’re wondering about a little bump that grew after shaving and probably results from irritation, stop shaving for a month or two and see if it shrinks or disappears.

You may get your answer without a trip to your doctor.

Once your visual inspection is complete, move on to a manual examination.

Gently hold your testicle (first one, then the other) between thumb and forefinger and work your fingers methodically over the surface from top to bottom, then front to back.

(See

Figure 8.

1

.

) Your testicle should have a uniform consistency.

Any hard lumps or irregularities, no matter the size, need to be shown to a doctor.

Don’t be afraid of pushing one testicle across to the other side.

The two halves of your scrotum are separated by a membrane.

Some men worry that they will push their testicle up and out of their scrotum, where it will get stuck in their inguinal canal.

Impossible.

Your testicle rises and falls with your spermatic cord, and as long as your testicle descended properly, it will never leave your scrotum.