The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself (39 page)

Read The Invention of News: How the World Came to Know About Itself Online

Authors: Andrew Pettegree

War and Rebellion

I

N

1618 the edgy, brooding truce that had kept the peace in central Europe for over seventy years stood on the brink of collapse. A resurgent Catholic activism had caused Protestants to fear that the liberties guaranteed by the Peace of Augsburg in 1555 would not be long maintained. The prospect that the Emperor Matthias would be succeeded by his much more militant cousin Ferdinand stirred anxiety in the Habsburg lands, particularly in Bohemia where Protestants were a long-standing majority. The crisis came to a head in Prague on 23 May 1618, when Protestant deputies from the Czech Estates confronted loyal imperial regents. After angry exchanges two prominent imperial officials were hustled to a high window of the castle and hurled through it. Their unfortunate secretary was tossed after them.

Miraculously, all three survived the sixty-foot drop. The victims landed on a pile of refuse and were able to stagger away, largely uninjured. For the Protestants of Bohemia this unexpected denouement was an ominous portent of ill-fortune. For the Emperor's supporters, on the other hand, the survival of the defenestrated officials offered a remarkable propaganda coup. News of their escape circulated swiftly around Europe, though presumably not everyone believed the excited accounts of reported bystanders who claimed that they had seen the Virgin Mary intervene to cushion the fall.

1

The victims themselves were grateful enough for the providential dung-heap.

The defenestration of Prague would usher in thirty years of warfare that in due course drew in almost all of Europe's major powers. It was immensely destructive for Germany, and led to permanent shifts in the European power structure. It was also the first European conflict to be fought in the full glare of the new news media. The Thirty Years War erupted only a few years after the introduction of the new postal routes linking northern Europe to the imperial system, and the establishment of the first newspapers. It would be a remarkable

test for the capacity of the new communications network to provide news and analysis to Europe's anxious and suffering peoples. These developments, of course, were not confined to Germany. By the time Protestant and Catholic powers were finally brought to the negotiating table, new conflicts, the Fronde in France and the British Civil Wars, were testing the capacities of the new media to incubate opposition and marshal opinion. This was an age in which news media sought a wider public, and where a wider public was desperate for news. The impact would be profound and long-lasting.

From Prague

In the years after 1618 those waiting anxiously in Europe's capital cities for news of events in Germany would have many occasions to praise the industry of Johann von den Birghden, the imperial postmaster of the newly established station at Frankfurt. For it was von den Birghden who had personally ridden to Prague to see to the placement of the postal stations that connected the imperial capital to the German postal network and thus linked up the rest of Europe, through Frankfurt, to the tumultuous events in Bohemia.

2

With the defenestration of Prague the Bohemian Revolt had passed the point of no return. By throwing off Habsburg allegiance and electing the Protestant Frederick of the Palatinate as King of Bohemia in place of the deceased Matthias (August 1619), the Protestant Estates ensured that only military conflict would settle the issue. These extraordinary events provoked the customary rash of celebratory or disapproving pamphlets: many offered a remarkably serious and measured response to the constitutional crisis in the Empire, which had now entered uncharted waters.

3

The war was also the first test of the new weekly newspapers. Since 1605 the printed news-sheets had been set up in at least half a dozen towns, and this would double in the first years of the struggle.

One of the first reports of the defenestration of Prague appeared in the

Frankfurter Postzeitung

. Citing a despatch from Prague dated 29 May (six days after the event), the paper accurately reported that all three victims had survived, but was mistaken as to their names.

4

The next issue of this paper does not survive, so we cannot tell whether it published a correction. Although mistaken in some of the particulars, the sober tone of the reporting is utterly characteristic. Correspondents wrote as they would for their fellow diplomats and officials. They made no concessions to the fact that these reports might, through the newspapers, reach a wider public: they felt no duty to explain, to sketch the background, or introduce the persons named. The journalistic instinct to popularise and enliven reports of current events

that we have witnessed in the sixteenth-century pamphlet literature is entirely absent.

The German newspapers of these years also carried reports from both sides of the developing conflict, with little attempt to differentiate or slant them towards the likely allegiances of their readers. In the circumstances of an increasingly bitter and bloody conflict such an unpartisan spirit could not endure. In 1620 readers in Hamburg, Frankfurt or Berlin could read reports from Prague and Vienna that would, in the case of the Bohemian despatches, speak of ‘our King Frederick’ or ‘the enemy’, whereas the Viennese despatches in the same issue offered a loyally imperial perspective.

5

An even more clearly differentiated market emerged with the establishment in 1622 and 1623 of newspapers in the confessional citadels of Vienna and Zurich. The first generation of German newspapers had all been established in the cities of north and central Germany. Thanks to the efficiency of the new postal routes, news entrepreneurs in these cities had access to a full range of reports from all the main stations of European politics. In contrast Matthias Formica, the founder of the first newspaper in Vienna, had no correspondents in Protestant areas: he would hardly have been able to print in the Habsburg capital their eager accounts of the usurpation of the Bohemian Crown in any case.

6

The Zurich newspaper also developed into a highly partisan organ on the Protestant side. But even that paper could do little to disguise the scale of the calamity that was unfolding. Disappointed in his hopes of support from other major Protestant powers, the newly elected King of Bohemia, Frederick of the Palatinate, was swiftly deposed by one Catholic army, while another laid waste to his Rhineland territories.

Faced by this rampant Catholic power, publications elsewhere in Germany also began to choose their words more carefully. This was not, it should be said, the result of any aggressive action by their own local rulers. In 1628 the city council of Berlin examined the printer of its own local paper after some grumbling from Vienna about the nature of its reporting. The printer protested that he simply published incoming reports as he received them, without altering a single word. This statement of general practice was accepted as reasonable, and no further action was taken.

7

Merely to keep abreast of the extraordinary events of these years was a sufficient challenge for the first printed news-sheets, which seldom, even with the most dramatic news from the battle-front, deviated from the established format of four or eight closely written pages of sequential reports from the leading news centres. As the Catholic forces moved to consolidate their battlefield victories, with the deposition of Frederick and the investiture of Maximilian of Bavaria with his former Electoral title, even the pamphlet

literature struggled to find an adequate response. Anxious commentary on the constitutional implications of the erosion of liberties guaranteed by the Confession of Augsburg did little to deter the Emperor from pressing home his advantage. For a true expression of the passion and confessional fury of these years we need to turn to another news medium: the resurgent trade in illustrated broadsheets.

8

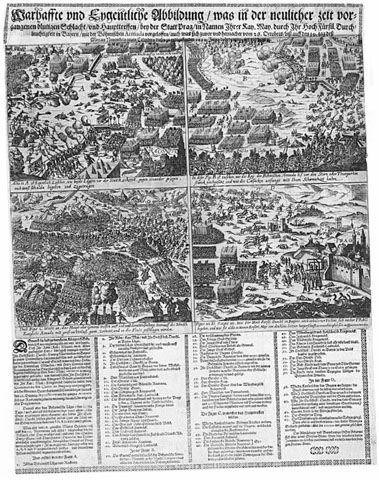

10.1 The Bohemian war, here described in sequential illustrations.

Lampooning the Winter King

In the sixteenth century broadsheets had tended to avoid political subjects: their major function was as a vehicle for the spreading of sensational news: lurid crimes, misbirths, miraculous apparitions and the like.

9

The sole exception was their role as a polemical tool in the Reformation conflicts. As this might imply, in the sixteenth century the polemical broadsheet had largely been a Protestant medium.

10

The major centres of woodcut production were in cities, like Nuremberg and Augsburg, where the evangelical movement had made an early impact, and Martin Luther's followers soon employed the skills of these artists to build support for the new movement and heap ridicule on the Pope. Just before the outbreak of the Thirty Years War the first centenary of the Reformation had prompted a new wave of pious images of Luther and other fathers of the Reformation.

11

Now, in the early seventeenth century, stimulated by the potent political events in Germany, the broadsheet would demonstrate its full potential as an instrument of political propaganda. This was the golden age of the illustrated broadsheet: in place of the woodcuts of the sixteenth century, publishers made increasing use of copperplate engraving, which allowed for greater fineness of detail.

12

Later in the century, as the market declined somewhat, the woodcut would return as more sophisticated customers abandoned the broadsheet. But in the period of the Thirty Years War political broadsheets found an eager audience among precisely the same sophisticated urban clientele who were fuelling the growth of the newspaper.

In the first years of the Bohemian conflict printers in the Protestant cities cheered their customers by teasing and goading the Jesuits, newly expelled from Bohemian lands.

13

The Jesuits were widely blamed on the Protestant side for the new militancy among the Catholic leaders, and they remained a target for Protestant antipathy throughout the war. The woodcut artists also developed a neat allegory with Frederick, the new Protestant hero, tending and healing the Bohemian lion, wounded as it fought its way clear of the Habsburg thicket: a rather charming re-imagining of the well-known tale of St Jerome with the lion, presented here in an evocative strip cartoon.

14

All this changed in the most dramatic fashion with the Protestant defeat at the battle of the White Mountain (8 November 1620). The humiliation of the Protestant armies, followed by the ignominious flight from Bohemia of Frederick, now contemptuously dubbed the ‘Winter King’, represented a complete reversal of fortune, and Catholic writers were quick to drive the message home. Celebrations of the Catholic heroes were accompanied by an outpouring of scorn for the Protestant leaders. A particularly popular cartoon

shows a post boy riding through Europe seeking the missing Winter King; the woodcut, accompanied as ever by mocking verses, shows the perambulation as a sort of primitive snakes and ladders board.

15

The motif of the Bohemian lion is now reversed: caught in the act of assaulting the imperial eagle, it is mauled by the Bavarian bear, a reference to the leading role of Maximilian of Bavaria as Catholic champion.

16

This was a true cartoon, in that it scarcely needed the accompanying verses to make its point: indeed, a number of editions were published with no text at all. Another delightful cartoon showed the Protestant leaders gathered round a table in pointless inactivity while the Marquis of Spinola systematically reduced the Rhineland strongholds in Frederick's former Palatinate.

17

Like many cartoons this was not an unfair statement of political reality. Concerned at their own individual vulnerability and divided by confessional and dynastic rivalries, the Protestant princes did little to contest the inexorable Catholic advance. Their own presses could offer little to raise the spirits, beyond a few sour and superior remarks about the quantities of useless print in circulation.

18

In 1621 the city of Nuremberg stripped the previously favoured engraver Peter Isselberg of his citizenship when he was unwise enough to publish in this Protestant citadel a polemical broadsheet against the Winter King, but such vindictiveness could do little to stem the tide.

19

The desire to blame the messenger is evident also in the first of a long series of lampoons against news-writers, accused of satisfying a gullible, news-hungry public with false reports. True or false, the news for the Protestant cause was unremittingly bad. A decade of military disaster came to a calamitous climax when in 1631 the armies of the imperial general Count Tilly stormed the city of Magdeburg and put it to the sword. A staggering 85 per cent of the population of this iconic Protestant citadel (the heartland of resistance to the Emperor a century before) lost their lives in the sack and ensuing fire.