The Italian Boy (33 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

Rebecca Baylis was a new witness; she also lived opposite the Birdcage, at 1 Virginia Row, which approached the pub from the southwest. “On Thursday 3rd November, about a quarter before twelve o’clock, I saw an Italian boy. He was very near my own window, standing sideways. I could see the side of his face and one end of the box, which he had in front of him. I think it was slung round his neck. He had a brown fur or seal-skin cap on, a small one, rather shabby. I could see the peak was lined with green and cut off very sharp. [Here, she looked down at the cap in her hands.] It was this color … but the front appeared to me to come more pointed. It was a cap much like this. I cannot swear whether this is it. He had on a dark blue or a dirty green jacket and grey trousers, apparently a dark mixture, but very shabby. About a quarter of an hour after, I had occasion to go to The Virginia Planter [a pub in Virginia Row] to see if it was time to put on my husband’s potatoes. I went a little way down Nova Scotia Gardens to look for my little boy. I saw the Italian boy standing within two doors of Number 3. There are three houses together and he stood by Number 1. I do not think the jacket produced is the one he had on.… I thought it was darker. These have the appearance of the trousers he had on.” Curwood pressed her about the jacket. “No,” said Baylis, “it appeared darker at the distance I was, which was about six yards. I will not say it is the same.”

Another new witness, John Randall, laborer, told the court: “On Thursday morning 3rd November, between nine and ten o’clock, I saw an Italian boy standing under the window of the Birdcage public house, near Nova Scotia Gardens. He had a box or cage with two white mice—the cage part of the box went round. I turned round to the boy. I saw he looked very cold and I gave him a halfpenny and told him he had better go on. He had on a blue coarse jacket or coat, apparently very coarse, and a brown cap with a bit of leather in front. I did not notice whether it was fur or not. It was similar to this in color, and the jacket was this color. I did not notice his trousers.”

Sarah Trueby once again described the topography of Nova Scotia Gardens. Her husband, she said, owned Nos. 1, 2, and 3 and rented them out. The well in the Bishops’ garden was easily accessible: gates in the palings between Nos. 1 and 2 and Nos. 2 and 3 showed that this well was meant to be used by all three sets of residents. Many others could easily reach it too, though.

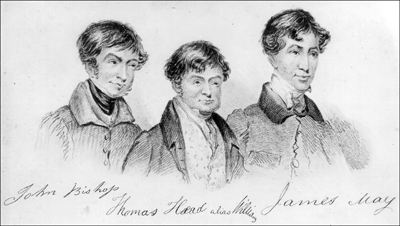

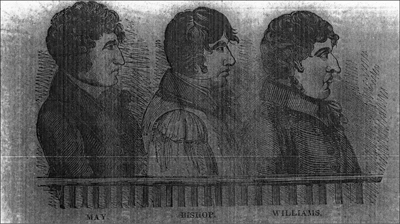

Two unconvincing Old Bailey courtroom sketches of Bishop, Williams, and May

All the Woodcocks, of 2 Nova Scotia Gardens, took the stand—twelve-year-old William to repeat his belief that Williams was living with the Bishops and that he had from time to time seen Rhoda doing her washing at No. 3; his mother, Hannah, to say the same; and William Woodcock senior to repeat his evidence about the noises that had awoken him in the early hours of Friday, 4 November, after what he guessed had been four or four and a half hours of sleep. He claimed that, without any doubt, one of the three voices he had heard during the scuffle belonged to Williams. Woodcock had chatted with him for around two hours on the afternoon of Sunday, 23 October, when Williams came up to the palings while Woodcock was gardening and dissuaded him from digging the soil at the bottom of the garden of No. 2, suggesting instead the area close to the cottage where, Williams said, some lily bulbs could be found.

Abraham Keymer kept the Feathers public house in Castle Street (the southwestern continuation of Virginia Row). He said that “about a quarter before twelve o’clock on Thursday night, 3rd November, Bishop came to my house with another person, who I think was Williams, but I am not quite certain of him. My house is one or two hundred yards from Bishop’s. I think they had a quartern of rum and half a gallon of beer—they took the beer away with them in a half-gallon can. This is the can.” Superintendent Thomas had seized it at No. 3 and proffered it as evidence. Keymer added that he could not be positive that Williams had come that night “as I had never seen him before.” This statement contradicted eyewitness evidence that Bishop and Williams had made the Feathers their last port of call when they made Fanny Pigburn drunk on the night of 8 October.

PC Joseph Higgins told of the digging up of Bishop’s garden and detailed the state of the clothing he had found one foot down, below a spot that had been scattered with cinders and ashes “which would prevent my noticing its having been turned up.” He told of the implements found in Bishop’s house and at May’s lodgings. The blood had been fresh on the brad awl and on the breeches found at May’s. The dug-up clothing was passed around the jury. The prosecution asked Higgins whether such clothes would have been “useful” to Bishop’s own children. “The coat would be very useful and has not got a rent in it. It would be very useful for a working boy.” So why would a family bury clothing that still had plenty of life in it? was the unvoiced question. Superintendent Thomas told the court that he had been requested by May to point out that the blood on the breeches had been so fresh that it must have been shed after his arrest; Thomas felt it only right to make that point clear on behalf of the prisoner.

Edward Ward of Nova Scotia Gardens came into the witness box. He told the court that he knew that it was a very bad thing to tell a lie, that it was a great sin. He said he knew that people who lied went to hell and were burned in brimstone and sulfur. Then he took the oath. He was six and a half years old. “I remember Guy Fawkes day—my mother gave me a half-holiday before Guy Fawkes day. I do not recollect what day of the week it was. I went to Bishop’s house on the day I had the half-holiday. He lives in Nova Scotia Gardens at a corner house. I have seen three of his children—he has one big boy, another about my age, and a little girl. I saw them that day in a room, next to the little room, and the little room is next to the garden. I played with the children there. I had often seen them before.”

“Did the children show you anything that day?” the prosecution asked their witness.

“Yes. Two white mice—one little one and one big one. They were in a cage, which moved round and round. I never saw them with white mice before, nor with a cage. I often played with them before. I saw my brother John when I got home and told him what I had seen.” Brother John confirmed that Edward had told him about the mice and the cage, and said that the half holiday from school had been on Friday, 4 November.

10

PC John Kirkman of F Division stepped up and reported that he had been watching over the prisoners in the Covent Garden station house late in the afternoon of Saturday the fifth. Repeating what he had told the coroner’s court, he testified that Bishop stood and read a printed bill on the wall about the King’s College corpse. “It was the blood that sold us,” Bishop had muttered to May, over the head of Williams.

This was the case for the prosecution. Curwood announced that he felt it was his duty to ask that the murder charge against Thomas Williams be dropped; his client was clearly not a principal in the crime, though Curwood conceded that he may have acted as an accessory after the fact. It was true that very little of what had been presented in court connected Williams even to the bartering of the body; by Bishop’s own admission, his stepson-in-law/half-brother-in-law was very new to the trade; and none of the resurrection community had appeared even to recognize Williams. But Lord Chief Justice Tindal was having none of it. He told Curwood that it would be up to the jury to decide the guilt or innocence of Williams, as charged.

* * *

Now the defens

e did what the defense was restricted to doing: putting forward the written statements of the accused and bringing forth the defense witnesses. An officer of the court read the statements out. Bishop admitted that he had been a body snatcher for twelve years, though, probably on the advice of his attorney, he described his work as “procuring bodies for surgical and anatomical purposes.” Then he stated:

I declare that I never sold any body but what had died a natural death. I have had bodies from the various workhouses, together with the clothes which were on the bodies. I occupied the house in Nova Scotia Gardens fifteen months. It consisted of three rooms and a wash-house, a garden, about twenty yards long, by about eight yards broad, three gardens adjoin, and are separated by a dwarf railing. I could have communication to either cottage, or the occupiers of them to mine. The well in my garden was for the joint use of all the tenants. There was also a privy to each house. The fact is, there are twenty cottages and gardens which are only separated by the paling already described, and I could get easy access to any of them. I declare I know nothing at all about the various articles of wearing apparel that have been found in the garden, but as regards the cap that was found in the house and supposed to have belonged to the deceased Italian boy, I can prove that it was bought by my wife of a Mrs Dodswell, of Hoxton Old Town, clothes dealer, for my own son, Frederick. The front I sewed on myself after it was purchased. The front was bought with the cap but not sewed to it. They were sold to my wife along with other articles. Mr Dodswell is a pastry cook, and has nothing to do with the business of the clothes shop—the calling of Mrs Dodswell, therefore, as evidence to prove the truth of my statement, will put it beyond a doubt that the cap never did belong to the deceased boy, and Mrs Dodswell should also prove how long she had the cap in her possession, and how she came by it. As much stress has been laid upon the finding of several articles of wearing apparel, and also the peculiar manner in which they appear to have been taken off the persons of those supposed to have come in an improper way into my hands, I most solemnly declare I know nothing whatever of them. The length of the examinations and the repetition of them have been so diligently promulgated and impressed on the public mind, that it cannot but be supposed that a portion of the circumstances connected with this unfortunate case (if not all) have reached and attracted the attention of the jury. But I entreat them, as they value the solemn obligation of the oath they have this day taken, that they will at once divest themselves of all prejudice and give me the whole benefit of a cool, dispassionate and impartial hearing of the case, and record such a verdict as they, on their conscience, their honour, and their oath, can return. May and Williams know nothing as to how I became possessed of the body.

Toward the end of Bishop’s statement, lawyer language is clearly detectable; Williams’s brief statement bore the mark of a legal hand to a far greater extent: “I am a bricklayer by trade, and latterly worked at the glass-blowing business. I never was engaged in any instance as a procurer of dead bodies or Subjects. Into the present melancholy business I was invited by Bishop. I know nothing whatever about the manner in which he became possessed of the dead body. Bishop asked me to join him on the Friday. I made no inquiry about the nature of the business. I shall, therefore, leave my case entirely to the intelligence and discrimination of the jury and the learned and merciful judge, but I trust I may be allowed once more to state that I am entirely innocent of any offence against the laws of my country.”

May’s statement said that he had had a “moderate” education and

first became engaged in the traffic of anatomical Subjects six years since, and from that period up to the time of my apprehension have continued so, with occasionally looking after horses. I accidentally met Bishop at the Fortune of War, a house that persons of our calling generally frequent and are known there as such. Bishop wanted to speak to me, called me outside the door, and asked me where the best price could be procured for Things. I told him where I had sold two for ten guineas each, at Mr Davis’s, and I had no doubt I could get rid of that Thing for him at the same price. He said if I did, I should keep all I got above nine guineas to myself. There was no questions asked as to the manner in which the body had been procured, and I knew nothing about it. As to what has been said in the public papers, or the prejudice that exists against me, and the other prisoners, it is of no moment. I here declare that during all the years that I have been in this business, I never came into possession of a living person, nor used any means for converting them into Subjects for the purposes of dissection. I admit that I have traded largely in dead bodies but I solemnly declare that I never took undue advantage of any person alive, whether man, woman, or child, however poor or unprotected. I have not been accustomed to make application for bodies at the different workhouses and I now solemnly declare that I know nothing at all of the circumstances connected with the procuring of the body, which is suspected to be that of the one named in the indictment, nor did I ever hear, nor understand, how Bishop became possessed thereof. I shall, therefore, leave my fate entirely to the intelligence and discernment of the jury and the learned judge.