The Italian Boy (35 page)

Authors: Sarah Wise

They left the dock and were escorted back down the winding stone tunnels that led between the Sessions House and the prison, and up and across the Press Yard to Newgate’s condemned cells. Walking with them was the Reverend Dr. Theodore Williams, vicar of Hendon, magistrate, and prison visitor, who had called on Bishop every day while he was on remand; Bishop had been the recipient—willing or unwilling, it is not known—of the vicar’s visits during previous incarcerations. Now as they walked, Bishop told Dr. Williams that he wanted to confess to him at once; but the vicar said no, wait awhile, and urged him to speak when he was feeling calmer; the reverend would be happy to hear Bishop’s tale first thing the next morning.

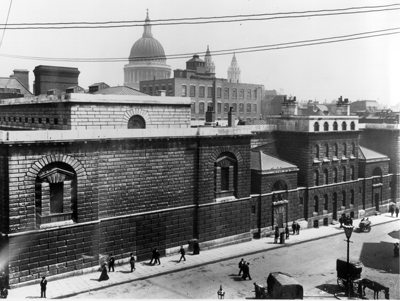

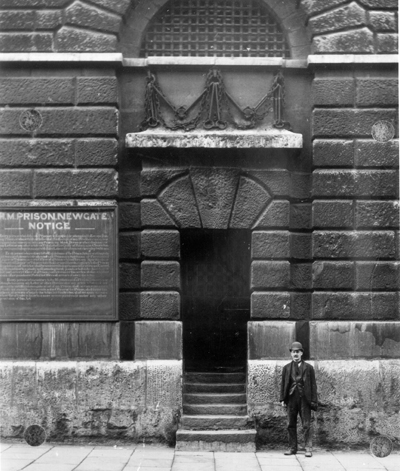

Newgate Prison and Debtors Door, photographed shortly before the building’s demolition in 1902

Sir Nicholas Conyngham Tindal, his fellow judges, the lord mayor, and the duke of Sussex had repaired to the private apartments above the Sessions House. Here, over dinner, the duke told the lord mayor that trials such as these made him proud of England, which had “the most perfect, intelligent and humane system.”

1

Evidently overheard by someone who was transcribing his words, the duke continued: “The judges of our land, the learned in our law, nobility, magistrates, merchants, medical professors and individuals of every rank in society, anxiously devoting themselves and co-operating in the one common object of redressing an injury inflicted upon a pauper child, wandering friendless and unknown in a foreign land. Seeing this, I am indeed proud of being an Englishman, and prouder still to be a prince in such a country and of such a people.”

In the condemned block, the three were searched to ensure they had no means of cheating the hangman and were then locked into their separate cells, each with two guards. The fifteen condemned cells (built in 1728 and retained when the prison was reconstructed, along with the Sessions House, in the 1770s) stood at the northern end of the Newgate/Old Bailey complex, three stories of five rooms, each nine feet by six, and nine feet high. A dark staircase leading between the floors, Charles Dickens would later note, was luridly lit by a charcoal stove.

2

The condemned block was built of stone that was three feet thick, and each cell was paneled with planks of wood. In summer, these were chilly rooms; in winter, bitterly cold. The cell door was four inches thick with a small, grated hole; the cell window was five feet from the ground and a foot high, double-grated and barred. At best, the cells were in semidarkness, and after sundown each was lit by a single candle. On the floor was a hemp mat, which acted as a mattress and was tarred to keep out damp and vermin, and a couple of horse rugs, which served as blankets.

3

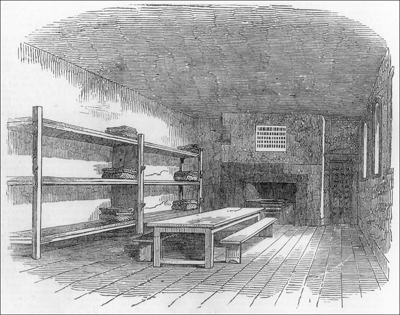

Separating the condemned cells from the rest of Newgate was the Press Yard, at the southern end of which were two “press rooms”—wards containing tables, benches, and a fire where the condemned were allowed to spend their daytime. In the Press Yard, remand prisoners used to be pressed to death by iron weights placed on a board if they refused to enter a plea of guilty or not guilty, an act that was viewed as treasonable; this

peine forte et dure

had squashed its last victim in 1726, but the memory of the ancient cruelty was retained in the name of the yard. It was just ten feet wide but seventy feet long, running down from the Newgate Street wall to the garden of the Royal College of Physicians (the college once backed onto the prison/Sessions House complex) and to another icon of the medical profession, Surgeons Hall, where, between 1752 and 1796, members of the Company of Surgeons had taken apart the bodies of the executed. (This had been the site of Sir Astley Cooper’s earliest triumphs, by his own admission: “The lectures were received with great

éclat,

and I became very popular as a lecturer. The theatre was constantly crowded, and the applause excessive.”)

4

Dare it be said, Newgate was not so bad. Not so bad as it had been. John Wontner had been in charge since 1822 and his governorship was regarded by many at the time as something of a golden age, though overcrowding continued to be a problem.

5

George Dance the Younger’s building was supposed to hold 350 prisoners, but in 1826 the population had reached 643, down from over 900 in 1815. (If two men were kept in the same cell, the warders had noted that “crimes have been committed of a nature not to be more particularly described.”)

6

Newgate housed both men and women (the ratio was four to one), though they were segregated, while children between the ages of eight and fourteen were kept in the “school” area. One of the most serious criticisms was that those awaiting trial mixed with the already convicted, the innocent and the novice being “contaminated” by the older felon, with the result that the same old faces would come back into the jail time and time again. No strenuous efforts were made here to “redeem” the criminal, unlike at Millbank Penitentiary. Compared with that at many other London jails, however, Newgate’s death rate was low, at three a year; and suicide was uncommon.

A sketch of the Newgate press room, where the condemned passed their remaining daytimes

There were no limitations on the number of visitors, and family and friends could bring in food and drink to augment the prison ration, which was in itself not ungenerous. Every day, breakfast consisted of half a pint of gruel; each prisoner had a pound of bread a day; and dinner alternated between half a pound of beef on one night and soup on the next, with vegetables and barley. The Newgate diet was a source of criticism, since it was said by many to be more plentiful and of better quality than the food eaten by the nonoffending poor outside the prison walls. There was no restriction on the amount of porter that could be drunk (it was safer than the water), and visitors noticed high levels of drunkenness among the inmates. The tradition of “garnish,” or “chummage,” had each new arrival buy a round of drinks for those who shared his cell or ward—under threat of humiliation, such as removal of his trousers. It is impossible to gauge the extent to which psychological bullying went on, though an idea of the mores of Newgate thieves in the late 1820s is suggested by the tale of one prisoner who found himself being shunned when it became known that during the robbery at the London Docks for which he was imprisoned, he had knocked unconscious his victim, an aged sea captain.

7

Physical violence among inmates was said to be rare, and rioting even rarer, with the only dissent tending to occur after lockup on the nights when the “transports” were announced—those who the next day would be taken, in “drafts” of twenty-five, to the hulks, either to finish their jail term there or to set sail for the other end of the earth. These announcements seemed to trigger anger and despair across the jail.

* * *

John Bishop slept

soundly in his cell and woke at around six on Saturday morning. The Reverend Dr. Theodore Williams, true to his word, turned up at ten. The vicar took Bishop into the room of Brown, the turnkey of the condemned block, and here, as the two men sat on either side of Brown’s table, Bishop began to reveal a number of most interesting matters—one of which was that James May had had no knowledge of how the boy’s body had been obtained, that he was entirely innocent and must have his death sentence overturned. Bishop continued, and the vicar’s pen flew over his notebook as he tried to capture the killer’s account. Suddenly there erupted into the room a party of furious men: Dr. Horace Cotton, the chaplain (or “ordinary”) of Newgate; prison governor John Wontner; and Alderman Wood, City sheriff. “Come, come, Mr. Williams,” said Dr. Cotton, “what is all this about? I suppose you want to extract confessions with a view to publishing them.” Dr. Cotton demanded that the confession stop immediately, and Bishop was ordered from the room and told to walk awhile with Brown in the Press Yard. Dr. Cotton told Dr. Williams that he had no right even to be in the prison, since these were condemned men and therefore came under the jurisdiction of the ordinary of Newgate. The extraction and publication—for money, via the newspapers—of condemned men’s confessions within twenty-four hours of an execution was among the perks of the ordinary’s job; it was one of Newgate’s many interesting old traditions, a practice sanctioned by the lord mayor of London and his court of aldermen. Alderman Wood told Dr. Williams that any written account of Bishop’s story would not be allowed out of the prison—it would have to be surrendered at the sheriff’s office. If Bishop were to go giving his account of events, it was highly likely that he would implicate others—hadn’t Dr. Williams remembered that Rhoda Head was still in custody on suspicion of being an accessory after the fact of murder?

The vicar of Hendon was astonished but not daunted, and when the party had swept out of Brown’s room and Bishop was brought back in, he asked the killer to pick up the tale—Bishop had just reached the most extraordinary part of it when the interruption had occurred. But Bishop would not go on. He had become dejected again, and said, “It is now of no use to implicate others.”

8

He was returned to his cell by Brown, and the vicar of Hendon went off to see if Thomas Williams had anything to say for himself. He did.

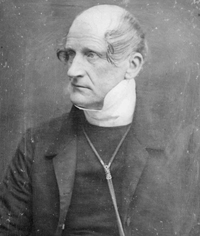

Theodore Williams, the controversial vicar of Hendon, photographed in old age

* * *

At around noon,

solicitor James Harmer was informed by Dr. Cotton that Bishop and Williams were in the process of making confessions and that anything they might say could compromise Rhoda. So on Saturday afternoon, Harmer went along to Bow Street and asked Minshull to set Rhoda free, on the legal grounds that she could not be held accountable for any crimes that her husband may have compelled her to commit. Besides, with Rhoda out of danger, the men would feel able to tell everything. Minshull saw the wisdom of this stratagem, and so it was that late on Saturday afternoon, Rhoda found herself in a coach with James Harmer traveling to Newgate. There, in one of the press rooms, “a most affecting scene” (according to the

Morning Advertiser

) took place, as Rhoda was reunited with Bishop and Williams. All three wept, and she told them that they must feel free to make the fullest confession possible and not worry about her and Sarah.