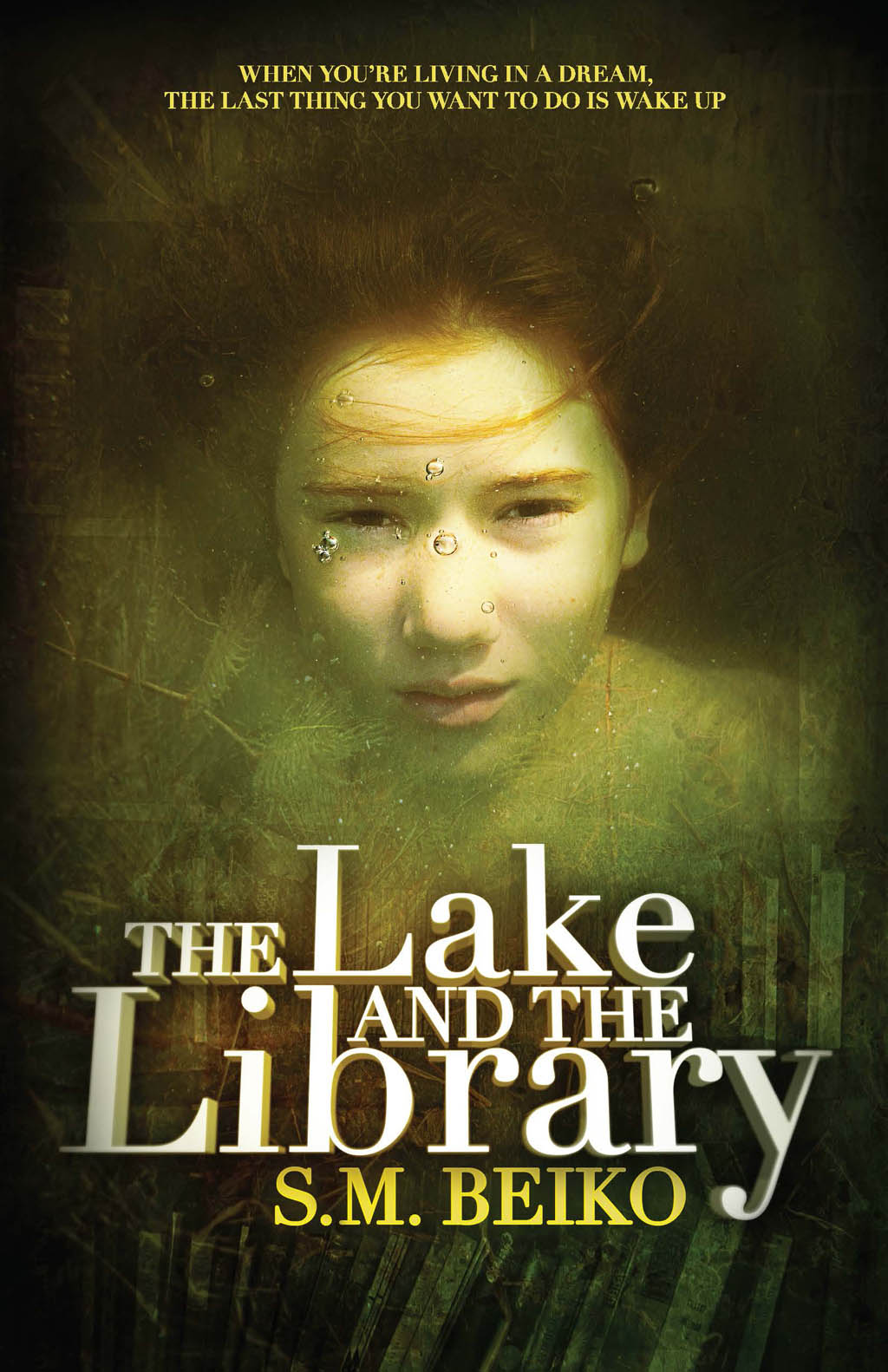

The Lake and the Library

Read The Lake and the Library Online

Authors: S. M. Beiko

For my mother â the original dreamer

She walks barefoot through the town. Her senses are lit up in a way she no longer thought was possible. The crisp smell of earth beneath her fine-boned feet. The wind tugging desperately at her robe, her brittle hair, hair that shone gold only a year ago, now hanging limp and white. Her legs had forgotten just what kind of effort it took to get to the lake, especially the climb up the rocky hill to get a good look above it. She's had to stop to rest a number of times already. The wind is still clawing at her, trying to get her to turn around. But she can't. Not now.

She hasn't been here in a long time. When she considers the way things have turned out in the last year, she realizes she hasn't really been anywhere in a while, that her wallpaper and pillow have been her only bits of engaging scenery. Surrounded by doctors and household staff â that is when she felt most alone. But here, on a cliff above the lake, watching the surface of the water bristle and break as the breeze churns the surface, she feels like she's in good company at last. She raises a hand in front of her, reaching, making it level above the water, pretending for a moment that she's floating. And what she's dreamt of for months from her sickbed in a tangle of despair and guilt, it's there, right there. And so is he. It's all she'll ever need.

She takes a step. Then another. And another. She is still reaching.

C

anvas. Brush stroke. Palette. The light caught the colour and made a clever shade, and I painted on. My work was trying too hard to be a masterpiece, and I was too impatient to let it become one.

“Do you know where you're going yet?”

I looked up from my canvas. Tabitha blinked once, waiting, expecting an answer.

I blew a strand of hair out of my eyes, ignoring the glassiness of hers, and I shrugged. “Northeast. Winnipeg, to start. Maybe Halifax, someday. Basically as far away from the prairies as we can get.”

I glanced at Tabitha's shoulder, which was quaking from strain. She'd been bravely holding the same pose for half an hour. Clad in a set of old drapes, striped socks, a puffed crinoline, and a promise, she swallowed back what I didn't realize then were tears, a bodily fluid forbidden by her personal code of casual humour. Though she stood with dubious integrity, with

conviction

, she blinked hard.

I was leaving, and this time, Tabitha couldn't follow me.

“You just want to get away,” she sighed through half a laugh. “From

me

.”

I was already on my feet, twisting the easel into the dimming sunlight, letting the summer air dry the colours

,

as Tabitha slumped down to the edge of my bed, her long would-be model's legs vanishing into the folds of endless gauze. My arms were instantly around her shoulders. I chewed the inside of my cheek, but I had no sage words or scraps of poetry to convince her she was wrong.

“There's still the summer,” I reminded her. “Loads of time! And it's not like I won't come back to visit. Like I could forget you guys!”

“Then why did you always want to leave so badly?”

I nudged her shoulder with my forehead, biting the inside of my cheek even harder. What kind of answer could I have given her?

I need to get out and go, find somewhere just for me. Treade isn't it. I need a field of sunflowers, a hill to roll off, a sea to be swept away by instead of docked at.

Sixteen is the age when you don't know what you want.

“Just for a change, that's all,” I said. “For something . . .

else

.”

We sighed and contented ourselves with the gold foil rays escaping out the window. On the canvas, there danced a princess in the stars. Her eyes were shut indignantly, gladiolas and lilies and birds in her hair. I don't think she knew which way to turn when the next dance step came, even if it meant falling out of the frame.

“There's still the summer,” we agreed at last.

“We're leaving.”

That was how my mother had told me. Needless to say, I barely made a tremor on the sofa as she stood in the doorway, cigarette smoke dancing around her head in a halo. The statement formed a weight at my mother's mouth, and lifted one from my chest.

“Leaving. Really? Like . . . really, really.”

“Really, really,” she smiled, the gap in her front teeth making a shy appearance as she butted out in her bronze ashtray. “I've already applied for a transfer from Treade General.”

We are leaving

. My mind exploded in a supernova of

yes.

I did not need the withheld explanation for

why.

My already overtaxed imagination did not require a

where.

My face worked and worked, but I couldn't shave off the grin.

“When?”

“At the end of summer, just in time for school.” Forever trying to be practical. But she was grinning, too. I knew she wanted to get out of Treade just as much as I did. We crowed and plotted, and as the realization that we were finally going to make our escape bloomed under my rib cage, it was a Goldilocks moment: it felt

just

right

.

Ten years we'd wasted in this sullen landscape, and my feet had been itching to run wild from it the entire time. There was no magic in Treade that I saw â there probably never was, even though my desperate eyes turned over every rock to find it. I only saw the town's bitter, broken spirit deriding me constantly through the billowing fog above the Maczik family's ethanol plant. I saw rusted echoes of ghosts in garden gates, ghosts long gone and pleased by it. Their only legacies were inherited sneers, flaking buildings, and deep shades of grey stained into the prairie false fronts. Treade felt like a mannequin, a stand-in for something alive. I saw no chic, rocking jive or sweating drummers, no sidewalk jewel shops, surfing princes, or ancient tales that could shape me into something otherworldly. Treade was so far from the adventure I longed for when we moved here. A vacuum for dreamers.

Abandoned farm buildings were all that was left to house fifty-year-old good intentions. The original town hall stood empty, boarded up and ignored by those who walked by it. The short and often impassable Main Street started with nowhere and ended with a single, dangling stoplight. Treade hadn't recovered since the Depression, and it was clear that everyone should have abandoned the place when they had the chance.

On the western edge of town, just past the spillway, the sprawling ethanol plant was the destination towards which every high school student had pointed his or her compass. That was their end. But not mine. I could see further than that dingy factory, deeper into the world beyond the white fumes above it. Ahead and away was the only place I could look, because there was nothing to see in Treade. The town had forgotten its history, its own

spirit

somehow, and what fragments it still recalled went unspoken like the punctured memories of an Alzheimer's patient. With its rain, its dusty bracken, darkened doors, and feverish youth, a town could never have been more wrong for me. For

us

.

And we were leaving it behind â

at last

. At long, deserved, light-on-the-horizon, holy-Lord-run-for-the-hills, my-life-is-finally-going-to-begin last. Treade would be just a memory filed away, and everything would be different.

It was different, too, when Treade was just a dream and I could shape it as I wished. When I was six years old, my mother had come to me â the then cosmic kindergartner â with her broken heart, jittery nerves, and wanderlust. “We've just got to go,” she had said. “There's a whole other world out there, sweetie, made of flickering stardust, and we have to capture it for ourselves.” And before my flitting, still newborn perception could adjust, I was cruising in our getaway car, my Care Bear backpack stuffed to the gills with crayon drawings of Alice falling down the rabbit hole into Xanadu (because all of these varied worlds, to me, were connected in their own way). Although I didn't get it, didn't know what was ahead, she held me tight, nose to nose, and that was another Goldilocks moment. Just right.

And I didn't ask the

why

then, either. But I should have.

Adventure, escape.

There has to be something out there just for me

, little Ash thought.

It's hard to be disillusioned when you're six and your entire world is saturated with Disney movies and dreams being wishes my heart made. I saw the world as changing, the kaleidoscope shifting to show bright possibility. It was going to be magical.

But Treade was not the Wonderland I was promised. When I asked Mum later what

really

brought us here, maybe a bit too late, she just laughed, her grey eyes gleaming, cigarette in one hand, smile full of mischief and maybe regret.

Adventure

,

her eyes said.

Escape

.

But those things weren't to be found in Treade. Not by a long shot.

“It's by the sea,” Mum had said. I believed that, too. Beyond the Firebird's windows, as the grainy desert shifted into a grassy one, I waited patiently for ever-stretching tides whispering mythic gossip to the shore.

By the sea.

She always said we would go there. She used to say that the wide and rolling waters were the world's last freedom, cradling the continents and singing lullabies to the stars. The sea outlived us all, she said, and like us, it couldn't be owned. Our own oceanic blood sang in harmony with these myths. We were nomads; we left and were left, and we preened in the wisdom of moving on.

The way my mother spoke, the smile in her eyes â oh, she could make me believe anything. Make me believe there was magic in Treade, that it was by the sea we craved. Instead, we found ourselves transplanted into a small Manitoba town that was dotted with a craggy lake and a single trafficlight that barely blinked. At the time, I smiled my two-front-toothless grin, and though my mother had lied, I believed Lake Jovan

could

be the sea. I believed we had made it to the promised waters of our dreams.

And deeply, readily, Mum even believed her own words. She needed to â needed

me

to â and with a blood bond no outsider could make sense of, we understood each other without question. We were not born to stay still for long. Wherever we belonged, it was never where we were.

But we had stood still long enough. Finally.

Finally

.

“We're leaving,” she had said.

Two words. And I believed her.