The Last Supper (8 page)

Authors: Rachel Cusk

The fresco cycle of the Capella Maggiore took Piero ten years to complete. It seems that he worked with extraordinary slowness, though the technique itself is immediate and quick-setting. I think of his sympathetic image of Hercules and wonder whether painting was in truth a terrible labour for Piero, an agonising process of atonement, of putting right. He would apply wet cloths to the plaster at night so that he could work two days on a single section. His preparatory drawings and calculations took even longer than the painting itself, for he was always the mathematician. He would seem to want to persuade you that these two callings are one, to show you only what is eternal. Not what is explanatory or circumstantial or even real, but what is always and forever true.

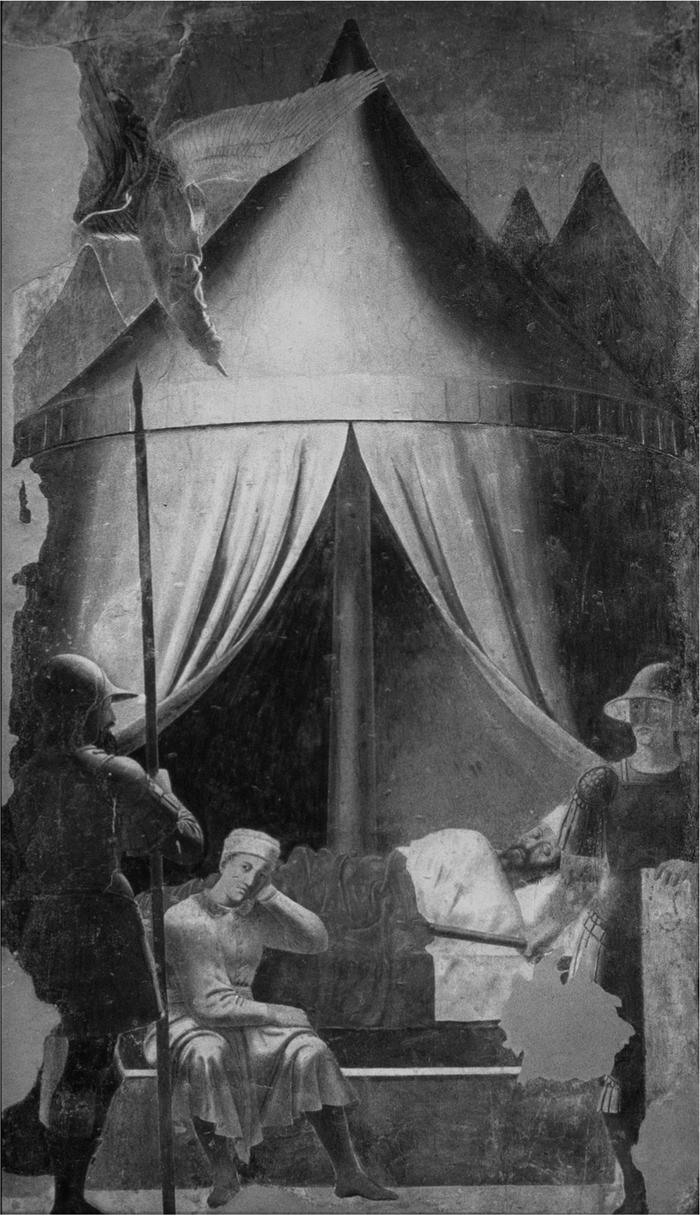

The Dream of Constantine

, from The Legend of the True Cross cycle, completed 1464 (fresco) by Piero della Francesca

He did not, I think, trouble himself over their subject matter, which is the Legend of the True Cross. This saga, which purports to tell of how the tree that grew from Adam’s body became the cross upon which Christ was crucified, is without doubt the religious story that makes its way most tortuously through human affairs. It features everyone from Cain and Abel to the Queen of Sheba. It features crusades and visions, evangelism and politics and unsavoury forms of Christian heroism. Yet entering the rectangular bay of the Capella for the first time is like passing from darkness into light; like looking out from a wintry room to a garden in summer, to blue sky and sunlight and trees. It is like emerging from imprisonment or blindness, and remembering what the world is really like.

*

I dream that my husband returns from town with armfuls of clothes that he has bought, fitted clothes in beautiful colours like the clothes Piero’s women wear, with intricate sleeves and pearl buttons. I presume they are for me and I see his surprise: clearly they are meant for our daughters, though he doesn’t say it and allows me to try them. One after another I try to put them on. They are all too small. The little pearl buttons won’t do up. My arms strain and tear the delicate sleeves.

In the Capella Maggiore there is a painting of the Emperor Constantine dreaming. How can such a thing be painted? Piero shows Constantine asleep, in a tent. The folds are parted to reveal him there, his eyes closed. The tent is so clear and firm, so tall and shapely and richly coloured, with the dim figure of Constantine inside. Though it is night, there is a strong light falling on its folds. The tent is the dream, more substantial than the dreamer. I wonder whether it is when we sleep that we are truly awake. As a child I entertained this fear: how beloved the concrete world seemed then, how horrible the lawlessness of dreams. There is an angel above Constantine’s tent: it is telling him that he must fight his enemy Maxentius in the name of the cross if he wishes to defeat him. This battle is waged across the adjacent wall, on horseback amidst a

bristling forest of lances. Above is the limpid, duck-egg-blue Sansepulcro sky, and in the background a little river meanders eternally through the green Tuscan fields like a ribbon of light, three tiny white birds afloat on its glassy surface.

The Death of Adam

, from the Legend of the True Cross cycle, completed 1464 (fresco) by Piero della Francesca

It is only by craning my neck that I notice the image in the Capella that afterwards I think of most. It is in the top right-hand lunette, a portrait of Eve as an old woman, attending Adam at his death. It is another mathematical truth, but of a different kind. She stoops in a dreary grey dress. Her wrinkled breasts sag. Her face wears that look so characteristic of the elderly, an expression of preoccupation with inalterable things. Her hand rests on her husband’s shoulder.

*

In the garden of the house the green geckos speed along cracks in the walls; the ants fulminate in their patches, carrying shreds of leaf like little sails that tilt and curve, winding through the

dirt and grass. The days are warm now. Around the wisteria the bees steadily drone and sketch their vague sweeping lines through the air. Caterpillars inch their way across vast expanses of paving stone, workmanlike, determined, and once I see a gecko dart out from a rock and, at the end of its long journey, snatch the furry body in its jaws and carry it away.

Madonna of Senigallia with Child and Two Angels

,

c

.1470 (tempera on panel) by Piero della Francesca

One day we go to Urbino, the last stop on the Piero della Francesca Trail. There are no queues in Urbino: the road is too winding, the location too remote. In the empty Galleria Nazionale we find Piero’s

Madonna di Senigallia

, austere, grey,

full of a cold northern light. It is a painting whose subject is purity, but it also seems to me to be some kind of statement. It is as if the artist is notifying us that he is withdrawing from the things of this world. In the background the light slants forever through the slatted window. The Madonna and her companions are silent, abstracted. The baby holds a white flower. The plain, pewter-coloured room contains them in its unadorned eternity. Yet they seem, somehow, to be taking their leave.

There is a meeting in the village in protest at the government’s plans to build a motorway east through the valley. The intricate, ancient vista, Piero’s vista, will be destroyed. An English lady is tearful at the prospect. Jim consoles her. Ach, it’ll take them years, he says. By the time they do it we’ll all be old and grey. It won’t make any difference to us.

I have understood, I think, Piero’s message, though its tidings are not of joy. It is at once more rational than joy and more beautiful. It is that you must seek a truth that lies beyond human concerns. I keep this with me as the days pass. The white birds on the water; the light slanting through the window. The man rising from his tomb, full of a terrible knowledge.

The children look at the castle across the valley. In the mornings we sit with them on the terrace doing schoolwork. We do maths, long pages of sums which they complete in their spidery handwriting. We do painting. We read aloud. The castle stands there, mystical and golden, its crenellations etched in shadow, and every so often they glance up at it. By now its romance is more real to them than their maths. They spring up from the table and run off to climb the cherry tree in the garden.

The castle is tall and thick and square: it is how I imagine Fabrizio’s tower to have been in Stendhal’s

Charterhouse of

Parma

. During his escape Fabrizio encountered certain problems caused by natural characteristics the building had acquired over time. Forests of gorse grew from its sides; it bulged and fell away unpredictably, had patches that were slippery as ice and others that were rough and so jagged they would cut the skin. Originally the production of man, the tower was reverting to nature, or acquiring a nature of its own. And indeed the village

castello

has something not human about it, despite its driveway and flowerbeds and swimming pool. A narrow road runs all the way around its perimeter, abutting the walls. From our house across the valley the walls look beautiful and soft, but close up they are as sheer and merciless as cliffs.

Jim, of course, is on terms of the utmost familiarity with the

castello

’s inhabitants. He comes and goes beneath those precipitous walls as blithely as he might cross the threshold of an overheated bungalow in suburban Dundee. He is keen

for us to have a look inside. He’s got us down as the sight-seeing type. He mentions a room in the

castello

where there are frescoes, and then looks at us out of the corner of his eye, as though half-expecting us to land on him in a body and tear him limb from limb in our excitement. For several days this visit is uppermost in Jim’s mind. Every time he sees us he mentions it, with increasing testiness, for having decided we ought to be given a tour of the

castello

it is not apparent to him why this should not occur immediately. The family agreed a time, he says, and then phoned to cancel it. He suggested another time and they haven’t yet got back to him. He doesn’t know what the problem is. He refers to personal difficulties for which it is clear his reserves of patience have run dry. Such human entanglements contravene the laws of Jim’s obliging universe, where the smoothing of paths and the offer of a helping hand are as inviolate as the sun and moon, or ought to be. I have noticed that Jim has quite a grand manner in the prosecution of this system. Its values are entirely social: their notions of right and wrong have no moral basis at all. His codes of conduct all grow from a single root, which is the protection of interests. For reasons which are unclear to me, the stand-off at the

castello

is running directly counter to the interests of all concerned, not least those of the owners themselves.

In Italy, gossiping, even of a scandalous kind, is a morally neutral activity; emotions, except as they force the hand of politics, are a public spectacle, like the opera. And like the opera they can engage our pity, our humour, our love of beauty and truth: they are greatly respected, but theirs is not the deciding vote in the judgement of human activities. Interests, and what advances or impairs them, are all. Jim is always willing to make an example of Tiziana, and he does so now. Tiziana’s interests and his own are fundamentally opposed. Three years ago she returned to the village after a period away. She had married, but the marriage quickly failed; she had lived in Spain for a while, worked as a teacher, moved here and there, but

nothing had come of it. So she came back, and moved in with her mother, who lived alone. Tiziana has built a wooden hut in the garden and that is where she resides. Nothing could better symbolise how temporary she intends her solitary state to be than this frail wooden hut; and nothing could better express the pent-up force of frustration that rages in her breast than the two giant, lavishly furred black dogs she keeps there, smothering them with a strange, suggestive care and kissing their snapping, sharp-toothed muzzles.

Jim, on the other hand, married very young and had a child. His wife was Italian, from Rome. Jim is half-Italian himself, which accounts both for his looks and for his sense of social intrigue. His grandparents came to Dundee as immigrants from a village in Liguria, and built an ice-cream factory which his father and now his brother continue to manage. Jim does not say much about the success or otherwise of this enterprise, but one day, in his apartment, he bashfully shows us a photograph of the family seat in Scotland, a vast aristocratic dwelling of considerable beauty and grandeur in whose vicinity for one reason and another Jim does not choose to live. Jim’s young wife moved to London with him; their son was born; Jim, by his own account, did not treat her well. She was homesick and lonely, and he was restless and disloyal. Eventually she left him and brought up the child alone. She has earned his respect over the years. He regrets the way he treated her. It was a great mistake. His son has been well educated and is now grown up. He is a good lad, good-looking and intelligent, and devoted to his mother. Jim, when he sees him, is reminded of some incapacity in his own nature that has been the chief source of pain in his experience of life. He doesn’t know what it is, only that it is there. And that his bachelor existence is both the expiation of it and the unique form of its relief. His top-floor flat is his sanctuary; and his retirement from the battlefield of married life, injured but not fatally so, is the piece of good luck on which he intends to last out his days.

It might be said that Jim is harming Tiziana’s interests by allowing her to cherish her hopes of him. He should let her go, and God knows he’s tried to get rid of her. They have often separated, but they always seem to drift back together again.

As for the denizens of the

castello

, well, they are the last in a line that extends unbroken across two centuries, though this epoch is now well advanced into twilight. The old man, Gianni, is on his last legs: his two daughters, both in their late forties, are childless. They are both married, but they continue to live in the

castello

with their father. The elder daughter lives a life of solitary, aristocratic dignity, doing good works in the village, riding her horses and advancing her studies of literature. She has the upright, un-self-pitying demeanour of a nun. I often see her striding about in jodhpurs and long leather riding boots and once or twice she has accosted me, wanting to talk about poetry, or an English novel she is trying to translate into Italian.

Her sister’s husband is Alfredo, a close associate of Jim’s. Their friendship is the perfect expression of Jim’s theories of social practice. Alfredo is a corpulent, slow-moving individual with a large, rough-skinned, pitted face of quite exceptional malevolence and dissipation. His small eyes look out of it with an expression of mingled torpor and amusement, like that of a boa constrictor who has just swallowed something large, and whose pleasant recollections of the event give way now and then to the sleepiness of a full stomach. He is often to be seen behind the tinted windows of a new silver Audi, slowly cruising the lanes and byways of the village, before disappearing back to Pistoia, where, according to Jim, he has a house. His visits to the village are territorial, like those of a shark cruising its habitual waterways. Once, we are walking along the unfrequented road back to Fontemaggio when the silver Audi glides quietly past and then draws to a halt just ahead with the engine running. The electric window slides down: there is Alfredo, leering at us from inside. He salutes us vaguely with his fat hand, on which he wears several heavy rings.

Va bene?

he says.

Tutto bene?

He looks us up and down. He grins. So, he says,

you are coming to see my house.

Casa mia

. We realise he is referring to the

castello

. We say that we don’t know, that Jim mentioned something, that everyone is very busy. He shrugs and grins again lazily and the darkened glass slides up in front of his face. Jim lives in fear of a summons to spend the evening with Alfredo: these are frequent, and put him out of action for a week afterwards.

Our invitation to the

castello

comes. The

signorina

meets us on the driveway, in severe riding habit and boots. She shows us her pet tortoises, who stumble around a fenced enclosure on the front lawn. Their wrinkled grey necks and blindly searching heads seem so vulnerable, protruding from their indestructible shells. She has other pets too, donkeys and goats and sheep she has rescued over the years. She keeps them in the stables, where the carriages used to be.

Other people arrive: Suzanne, the rotund American, and a couple from Milan. A car careers at breakneck speed into the driveway and Tiziana springs forth from its front seat, teeth bared and mane flying. The old man, Gianni, comes slowly towards us along a gravel path. His shoulders are bent; his head is fragile-looking, the skin a thin tissue threaded with veins, the eyes watery and depthless like a new baby’s. Yet his bones are large: they stand like the posts and beams of a ruined house amidst its decaying walls and roof. We are led inside, into a great hall as cold and bare as a monastery. The

signorina

talks: we follow her up a grand stone staircase, through empty rooms where the light slants undisturbed across the flagstones. In one room there is a pigeon. The

sig

norina

explains that it lives there. It is one of her protégés: it had a broken wing. Shortly afterwards we come to the frescoes: they decorate another empty room, to whose old varnished boards they impart a haunted atmosphere, for they remain bright and florid in the desolation, their scenes and figures unfaded. The

signorina

tells us they have been restored, lavishly so. No expense was spared. They have, themselves, no great distinction: the distinction lies in what

they are, for in Italy art is no longer permitted to die a natural death. People would say it was a shame, if the

castello

did not take care of its frescoes.

On the next floor, things change: this is the domain of Alfredo. We enter an elegant room with a great window and a lordly marble fireplace. The window has a view of the mountains behind the village. We went up there one day, and found a whole ghost settlement at the top, a place that no road leads to any longer. We walked in the overgrown cemetery and along the hollowed-out main street. The gardener at Fontemaggio tells us that his grandmother used to go every week to the market there. She lived in Arezzo, and would

walk all night across the mountains with her cows and her produce to buy and sell. The distance was twenty kilometres. She left in the early evening and arrived at dawn.

In front of the window stands Alfredo’s desk. This is his study. He is an architect: there is a framed certificate hanging on the wall. This room was created for him, in the hope that it might inspire him to work. The desk is made of polished engraved wood. It is a whole hand thick, and as big as a bed. Its surface is beautifully laid out, with fountain pens and compasses and drawing materials, all new. There is a block of unmarked paper and an empty leather chair, with its back facing the window. We pass into a sort of modern apartment, a vast room that extends the whole width of the castle, with leather sofas and low glass tables, sculptures in metal and wood, canvases and expensive lamps and books, and a whole glass wall that overlooks the valley. Jim regards this spectacle with a jaded air: this is where his evenings with Alfredo usually commence. There is an opulent bathroom next door, lined with marble from floor to ceiling like a tomb, and a bedroom with a black leather bed. Alfredo is apparently willing to rent this apartment to tourists. Suzanne says he has asked her to recruit victims from among her American acquaintances, but the rent is so high that nobody she knows can afford it.

Alfredo’s kingdom comes to an end: we go up, up a steep staircase and then up an even steeper one, and then up another, narrow and made of wood. Gianni follows all the way, arthritic but resolute. Tiziana holds the children’s hands, clutching at them with her long painted fingernails, shrieking concerned injunctions against falling, and flashing triumphant looks at Jim’s impervious back when she succeeds in getting them to the top unharmed. Finally, we come to a tiny door that lets us out on to the castle parapets. There is a narrow walkway all the way round. On one side is the castle roof; on the other is empty air. We file out. There below are the wave-like undulating hills, the village on its mound, the pale road that lies on the valley floor like a length of ribbon. There,

opposite, is Fontemaggio, and around it one or two other houses that on the ground are far away, separate and distinct in their own folds of hillside. The view from the top of the

castello

is not larger or more sweeping than the view from the village itself. It is the sudden effect of height that is unexpected. From above, the dimension of experience is lost, the feeling of involvement shrugged away. The earth goes about its own eternal business, rising and falling, growing or decaying; the late sun slants across it, the trees and houses correspond with their own little shadows. It is difficult from here to imagine time passing in minutes, in hours, to discern the intricacy of life, to distinguish one house from another, one day from another, one existence from any other. From here, only epochs are visible. We look down on it, as children believe people do from heaven. I do not like this feeling, of being separated from the earth. The soles of my feet prickle: I press myself back against the slant of the roof. I imagine the building tipping and throwing me out over the side into nothingness.