The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (22 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Potatoes prevent scurvy, provide quick and cheap meals for farm laborers

and their families, and require but the simplest of implements to plant and

harvest. Combined with milk or other dairy products, they made up a diet

that was far more complete nutritionally than the bread- and cereal-based

diets of sixteenth-century Europe. You would think that Europeans would

have embraced such a crop with immediate enthusiasm, but they did not.

Conquistadors regarded potatoes and the Andean Indians who grew

them with contempt. The potato was poor people's food, vastly inferior

to bread. Inevitably, strong social prejudice accompanied the few tubers

that came to Europe. After beginning their European career feeding patients in a Seville hospital for the poor in 1573, potatoes soon became a

botanical curiosity, even a luxury food, not a food for the indigent.

The new plant spread from garden to garden in the hands of ardent

botanists and their wealthy patrons. Potatoes appeared in the pages of

herbals, where readers learned that the Italians ate them "in a similar

fashion to truffles."15 In 1620, the English physician Tobias Venner

praised them in his Via Recta ad Vitam Longam ("The Right Road to a

Long Life") as "though somewhat windie, verie substantiall, good and

restorative." He recommended roasting them in embers, then dunking

them in wine. However cooked, "they are very pleasant to the taste and

doe wonderfully comfort, nourish and strengthen the bodie." Venner

prescribed them for the aged and remarked that the potato "incites to

Venus." 16 Despite these good reviews, many people thought them exotic

and poisonous. Potatoes were a root crop, not the kind of leafy plant

that could flavor or garnish roast meat. They occasionally appeared on royal menus as a seasonal food and were an expensive luxury. The English, not yet meat and potatoes folk, considered the potato an almost

indelicate plant that did not belong in the diet of a seventeenth-century

gentleman.

In 1662, a Mr. Buckland, a Somersetshire landowner, wrote to the

Royal Society of London arguing that potatoes might help protect the

country against famine. The Agriculture Committee of the Society

promptly agreed and urged its landowning Fellows to plant such a crop.

John Evelyn, the Society's gardening expert, wrote that potatoes would be

good insurance against a bad harvest year, if for nothing else than to feed

one's servants. In 1664, a pamphleteer named John Forster argued in a

book entitled England's Happiness Increased: A Sure and Easie Remedy

against the Succeeding Dearth Years that the potato was a sure remedy for

food shortages, especially when mixed with wheat flour. Deep-rooted social prejudices among the political and scientific elite prevented them

from setting an example and eating potato dishes. As for the poor, many

of them preferred to go hungry than to give up their bread.

French peasants resisted potatoes for generations. In bad years, they

made do with inferior or slightly moldy grain, suffered under ever higher

prices, became hungry, and often joined bread riots. The potato was still an

exotic food in France as late as 1750 and even then shunned by most gourmands. Burgundy farmers were forbidden to plant potatoes, as they were

said to cause leprosy, the white nodular tubers resembling the deformed

hands and feet of lepers. Denis Diderot wrote in his great Encyclopaedie

(1751-76): "This root, however one cooks it, is insipid and starchy.

... One blames, and with reason, the potato for its windiness; but what is a

question of wind to the virile organs of the peasant and the worker."17

In England, the potato was grown as animal fodder, then as food for

the poor, with flourishing potato markets in towns like Wigan in the

north by 1700. Across the Irish Sea, the Irish rapidly embraced the potato

as far more than a supplement. It was a potential solution to their food

shortages. Quite apart from other considerations, potatoes were far more

productive than oats, especially for poor people without money to pay a

miller to grind their grain. Soon the Irish poor depended on potatoes to

the virtual exclusion of anything else, a reliance that laid the foundations

for catastrophe.

The sun is only one of a multitude-a single star among millions-thousands of which, most likely, exceed him in brilliance. He is only a private in the host of heaven. But he alone

... is near enough to affect terrestrial affairs in any sensible degree, and his influence on them ... is more than mere control

and dominance.

-Charles Young, Old Farmers Almanac, 1766

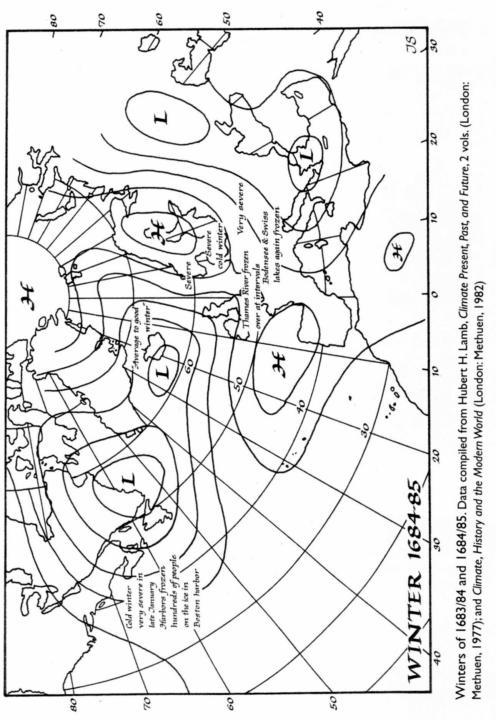

etween 1680 and 1730, the coldest cycle of the Little Ice Age, temperatures plummeted, the growing season in England was about five

etween 1680 and 1730, the coldest cycle of the Little Ice Age, temperatures plummeted, the growing season in England was about five

weeks shorter than it was during the twentieth century's warmest decades.

The number of days each winter with snow on the ground in Britain and

the Netherlands rose to between twenty and thirty, as opposed to two to

ten days through most of the twentieth century.' The winter of 1683/84

was so cold that the ground froze to a depth of more than a meter in parts

of southwestern England and belts of sea ice appeared along the coasts of

southeastern England and northern France. The ice lay thirty to forty

kilometers offshore along parts of the Dutch coast. Many harbors were so

choked with ice that shipping halted throughout the North Sea.

Conditions around Iceland were now exceptionally severe. Sea ice often blocked the Denmark Strait throughout the summer. In 1695, ice

surrounded the entire coast of Iceland for much of the year, halting all

ship traffic. The inshore cod fishery failed completely, partly because the fish may have moved offshore into slightly warmer water, but also because

of the islanders' primitive fishing technology and open boats. On several

occasions between 1695 and 1728, inhabitants of the Orkney Islands off

northern Scotland were startled to see an Inuit in his kayak paddling off

their coasts. On one memorable occasion, a kayaker came as far south as

the River Don near Aberdeen. These solitary Arctic hunters had probably

spent weeks marooned on large ice floes. As late as 1756, sea ice surrounded much of Iceland for as many as thirty weeks a year.

Cold sea temperatures brought enormous herring shoals southward

from off the Norwegian coast into the North Sea, for they prefer water

temperatures between 3 and 13°C. English and Dutch fishermen benefited from the herring surge, while the Norwegians suffered. This was

not the first time the fish had come south. In 1588, in a previous cold

snap, the great British geographer William Camden had remarked how

"These herrings, which in the times of our grandfathers swarmed only

about Norway, now in our times ... swim in great shoals round our

coasts every year."' The revived fisheries brought a measure of prosperity to Holland, as the country fought for independence, as did the development of simple windmills for draining low-lying fields. But repeated storms and sea surges overthrew many coastal defenses and

inundated agricultural land. In Norway, the shortened growing season

was even more marked than further south, at a time when mountain

glaciers were advancing everywhere. The Norwegians turned the cold

weather to their benefit. Many coastal villages abandoned their fields

and began building ships to export the timber from nearby forests. Between 1680 and 1720, Norway developed a major merchant fleet based

on the timber trade, transforming the economy of the southern part of

the country.

The cold polar water spread southward toward the British Isles. The

cod fishery off the Faeroe Islands failed completely, as the sea surface temperature of the surrounding ocean became 5'C cooler than today. Just as

it had in the I 580s, a steep thermal gradient developed between latitudes

50' and 61-65' north, which fostered occasional cyclonic wind storms

far stronger than those experienced in northern Europe today. The effects

of colder Little Ice Age climate were felt over enormous areas, not only of

Europe but the world.

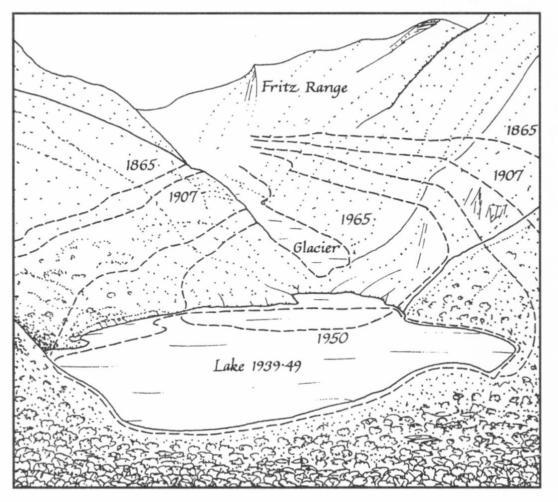

The retreat of the San Josef Glacier, South Island, New Zealand,

1865-1965. The glacier face has retreated even farther since the 1960s.

Redrawn from New Zealand Government sources; see also jean Grove,

The Little Ice Age