The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 (18 page)

Read The Little Ice Age: How Climate Made History 1300-1850 Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Gilles de Gouberville's archaic world was largely self-sufficient, his

identity closely tied not to his noble ancestors but to the land he and his

villagers inhabited. He cherished his ancestors for one reason alone: they

bequeathed the privilege of tax exemption. Given the constant threat of

sickness, hunger, and death, it is hardly surprising much of life revolved

around strong food and drink. Round bellied, with a brick-red, coarse

complexion, Gouberville and his gentleman contemporaries consumed

enormous meals. His journal records a supper for three on September 18,

1544, which comprised two "larded" chickens, two partridges, a hare,

and a venison pie. But most of his day-laborers and plowmen were

thrown into destitution and near-starvation when the harvest failed, for

cereals were the basic sustenance of all de Gouberville's people. (There

was only one disastrous harvest during the twenty years covered by his

journal.)

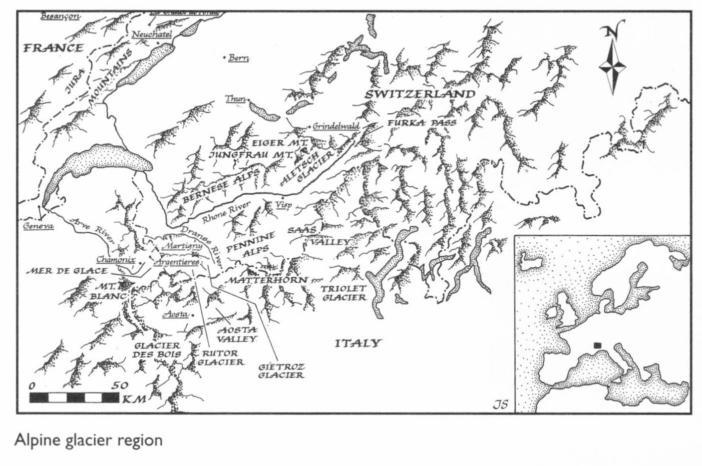

Gilles de Gouberville and his kind protected themselves and their people by diversifying their farming. Many European communities of the

day, especially those cultivating marginal lands in places like the

foothills of the Alps and Pyrenees, did not have that option. Like Icelandic and Norwegian glaciers, the European Alps are a barometer of

constantly shifting climatic conditions. Their glaciers have always been

on the move, waltzing in intricate patterns of advance and retreat

decade to decade that defy the best efforts of glaciologists and historians

to decipher. But we do know that the mountain ice sheets advanced far

beyond their modern limits as significantly cooler temperatures and

wetter summers descended on Europe after 1560.13 After the 1560s,

more frequent low NAOs brought persistent anticyclones over the

North Sea and Scandinavia.

Life in the Alps was always harsh: there were a "lot of poor people, all

rustic and ignorant." Strangers avoided a place where "ice and frost are

common since the creation of the world." The occasional traveler who

ventured to the mountains remarked on the poverty and suffering of

those who lived on the marginal lands in the glaciers' shadow.

On August 4, 1546, astronomer Sebastian Munster rode along the right

bank of the Rhone River on his way to the Furka Pass in the Alps, where he

wanted to explore the mountain crossing. All at once Munster found himself confronted by "an immense mass of ice. As far as I could judge it was

about two or three pike lengths thick, and as wide as the range of a strong

bow. Its length stretched indefinitely upwards, so that you would not see its

end. To anyone looking it was a terrifying spectacle, its horror enhanced by

one or two blocks the size of a house which had detached themselves from

the main mass." The water flowing from the glacier was a frothy white, so

filled with ice fragments that a horse could not ford the stream. Munster

added: "This watercourse marks the beginning of the river Rhone." He

crossed by a bridge that spanned the torrent just below the source.

The Rhonegletscher (Rhone glacier) was a formidable mass of ice in

1546, with a front between ten and fifteen meters high and at least two

hundred meters wide. Today, the tongue of the glacier is very thin, with a

height and width far smaller than in Munster's day. The ice sheet is high up

the mountain, the stream that becomes the Rhone now flowing through a narrow gorge and over several waterfalls. Munster rode up to the glacier

front. Today, the ice is accessible only by foot and that after an arduous

climb, and the landscape is entirely different from that of the sixteenth century. Yet, photographs from only a century ago reveal a glacier much larger

than it is today, this despite a slow and constant retreat from earlier times.

Between 1590 and 1850, during the height of the Little Ice Age, the Rhone

glacier was an even more impressive mass, readily accessible on horseback,

with a huge terminal tongue spread out over the plain.

In the sixteenth century, Chamonix, now a fashionable resort in the Arve

River valley in sight of Mount Blanc, was an obscure, poverty-stricken

parish in "a poor country of barren mountains never free of glaciers and

frosts ... half the year there is no sun ... the corn is gathered in the snow

... and is so moldy it has to be heated in the oven." Even animals were said

to refuse bread made from Chamonix wheat. The community was so poor

that "no attorneys or lawyers [were] to be had." Avalanches, caused by low

temperatures and deep snowfall, were a constant hazard. In 1575/76 conditions were so bad that a visiting farm laborer described the village as "a

place covered with glaciers ... often the fields are entirely swept away and

the wheat blown into the woods and on to the glaciers." The ice flow was so

close to the fields that it threatened crops and caused occasional floods. Today a barrier of rocks separates the same farmland from a much shrunken

glacier. The high peaks and ice sheets were a magnificent sight. Traveler

Barnard Combet, passing through Chamonix in 1580, wrote that the

mountains "are white with lofty glaciers, which even spread almost to the

... plain in at least three places."

On June 24, 1584, another traveler, Benigne Poissonet, was drinking

wine chilled with ice in Besancon in the Jura. He was told that the ice

came from a natural refrigerator nearby, a cave called the Froidiere de

Chaux. "Burning with desire to see this place filled with ice in the height

of the summer," Poissonet was led through the forest along a narrow path

to a huge, dark cave opening. He drew his sword and advanced into its

depths, "as long and wide as a big room, all paved with ice, and with crystal-clear water ... running in a number of small streams, and forming

small clear fountains in which I washed and drank greedily." When he

looked upward, he saw great ice stalactites hanging from the roof threatening to crush him at any moment. The cave was a busy place. Every

night peasants arrived with carts to load with blocks of ice for Besan4on's wine cellars. Another summer visitor, a century later, reported a row of

mule carts waiting to take ice to neighboring towns. As late as the nineteenth century, Froidiere de Chaux was still being exploited industrially.

As many as 192 tons of ice are said to have been removed from it in 1901.

But after an extensive flood in 1910, the ice never reformed, as warmer

conditions caused the glacier to retreat. No ice stalactites hang from the

roof of the cavern today.

The glacial advance continued. In 1589 the Allalin glacier near Visp to

the east descended so low that it blocked the Saas valley, forming a lake.

The moraine broke a few months later, sending water cascading down the

stream bed below the glacier, which had to be restored at great expense.

Seven years later, in June 1595, the Gietroz glacier in the Pennine Alps

pressed inexorably into the bed of the Dranse River. Seventy people died

when floods submerged the town of Martigny. As recently as 1926, a beam

in a house in nearby Bagnes bore an inscription: "Maurice Olliet had this

house built in 1595, the year Bagnes was flooded by the Gietroz glacier."

By 1594 to 1598, the Ruitor glacier on the Italian side of the Alps had

advanced more than a kilometer beyond its late twentieth-century front.

The glacier blocked the lake at its foot. In summer, a channel under the

ice would release catastrophic floods over the valleys downstream. After

four summer floods, the local people called in expert water engineers,

who proposed risky strategies: either diverting the lake overflow away

through a rock-cut tunnel or blocking the channel under the ice with

wood and stone for a vast sum. Tenders were invited, but, hardly surprisingly, there were no takers.

In 1599/1600, the Alpine glaciers pushed downslope more than ever

before or since. In Chamonix alone, "the glaciers of the Arve and other

rivers ruined and spoiled one hundred and ninety-five journaux of land

in divers parts."14 Houses were destroyed by advancing ice in neighboring

communities: "The village of Le Bois was left uninhabited because of the

glaciers." If contemporary accounts are to be relied upon, the ice advanced daily.

Near Le Bois, the Met de Glace glacier swept over small hills that protected nearby villages and hung over nearby slopes. The villages of Les

Tines and Le Chatelard were under constant threat from glacial seracs

(ice pinnacles) and were inundated with glacial meltwater summer after

summer. Ten or fifteen years later, the government official Nicolas de Crans visited the village, "where there are still about six houses, all uninhabited save two, in which live some wretched women and children.

... Above and adjoining the village, there is a great and horrible glacier of

great and incalculable volume which can promise nothing but the destruction of the houses and lands which still remain." Eventually, the village was abandoned.

The advances continued. In 1616, de Crans inspected the hamlet of La

Rosiere, threatened by a "great and grim glacier," which hurled huge

boulders onto the fields below. "The great glacier of La Rosiere every now

and then goes bounding and thrashing or descending. . . . There have

been destroyed forty-three journaux [of land] with nothing but stones

and little woods of small value, and eight houses, seven barns, and five little granges have been entirely ruined and destroyed." The Met de Glace

and Argentiere glaciers, the latter adjacent to La Rosiere, were at least a

kilometer longer in 1600 than they are today.

Throughout Europe, the years from 1560 to 1600 were cooler and

stormier, with late wine harvests and considerably stronger winds than

those of the twentieth century. Climate change became a highly significant factor in fluctuating food prices. Wine production slumped in

Switzerland, lower Hungary, and parts of Austria between 1580 and

1600. Austria's wines had such a low sugar content from the cold conditions and were so expensive that much of the population switched to beer

drinking. The revenues of the Hapsburg economy suffered greatly as a result. Deliveries of mice and moles killed for money dropped sharply after

1560, not to rise again until the seventeenth century. The Reverend

Daniel Schaller, pastor of Stendal in the Prussian Alps, wrote: "There is

no real constant sunshine, neither a steady winter nor summer; the earth's

crops and produce do not ripen, are no longer as healthy as they were in

bygone years. The fruitfulness of all creatures and of the world as a whole

is receding; fields and grounds have tired from bearing fruits and even become impoverished, thereby giving rise to the increase of prices and

famine, as is heard in towns and villages from the whining and lamenting

among the farmers."15

As climatic conditions deteriorated, a lethal mix of misfortunes descended on a growing European population. Crops failed and cattle perished by diseases caused by abnormal weather. Famine followed famine

bringing epidemics in their train, bread riots and general disorder

brought fear and distrust. Witchcraft accusations soared, as people accused their neighbors of fabricating bad weather. Lutheran orthodoxy

called the cold and deep snowfall on Leipzig in 1562 a sign of God's

wrath at human sin, but the church's bulwark against accusations of

witchcraft began to crumble when climatic shifts caused poor harvests,

food dearths, and cattle diseases. Sixty-three women were burned to

death as witches in the small town of Wisensteig in Germany in 1563 at a

time of intense debate over the authority of God over the weather. Witch

panics erupted periodically after the 1560s. Between 1580 and 1620,

more than 1,000 people were burned to death for witchcraft in the Bern

region alone. Witchcraft accusations reached a height in England and

France in the severe weather years of 1587 and 1588. Almost invariably, a

frenzy of prosecutions coincided with the coldest and most difficult years

of the Little Ice Age, when people demanded the eradication of the

witches they held responsible for their misfortunes. As scientists began to

seek natural explanations for climatic phenomena, witchcraft receded

slowly into the background. Only God or nature were responsible for the

climate, and the former could be aroused to great wrath at human sins.

Today, our ecological sins seem to have overtaken our spiritual transgressions as the cause of climatic change.16