The Monkey Grammarian (11 page)

As he created beings, Praj

As he created beings, Praj pati sweated and suffocated, and from his great heat and fatigue, from his sweat, Splendor was born. She made her appearance all of a sudden: there she was, standing erect, radiant, resplendent, sparkling. The moment they set eyes on her, the gods desired her. They said to Praj

pati sweated and suffocated, and from his great heat and fatigue, from his sweat, Splendor was born. She made her appearance all of a sudden: there she was, standing erect, radiant, resplendent, sparkling. The moment they set eyes on her, the gods desired her. They said to Praj pati: “Allow us to kill her: we can then divide her up and share her among all of us.” He answered unto them: “Certainly not! Splendor is a woman: one does not kill women. But if you so wish, you may share her—on condition that you leave her alive.” The gods shared her among themselves. Splendor hastened to Praj

pati: “Allow us to kill her: we can then divide her up and share her among all of us.” He answered unto them: “Certainly not! Splendor is a woman: one does not kill women. But if you so wish, you may share her—on condition that you leave her alive.” The gods shared her among themselves. Splendor hastened to Praj pati to complain: “They have taken everything from me!” “Ask them to return to you what they took from you. Make a sacrifice,” he counseled her. Splendor had the vision of the offering of the ten portions of the sacrifice. Then she recited the prayer of invitation and the gods appeared. Then she recited the prayer of adoration, backwards, beginning with the end, in order that everything might return to its original state. The gods consented to this return. Splendor then had the vision of the additional offerings. She recited them and offered them to the ten. As each one received his oblation, he returned his portion to Splendor and disappeared. Thus Splendor was restored to being.

pati to complain: “They have taken everything from me!” “Ask them to return to you what they took from you. Make a sacrifice,” he counseled her. Splendor had the vision of the offering of the ten portions of the sacrifice. Then she recited the prayer of invitation and the gods appeared. Then she recited the prayer of adoration, backwards, beginning with the end, in order that everything might return to its original state. The gods consented to this return. Splendor then had the vision of the additional offerings. She recited them and offered them to the ten. As each one received his oblation, he returned his portion to Splendor and disappeared. Thus Splendor was restored to being.

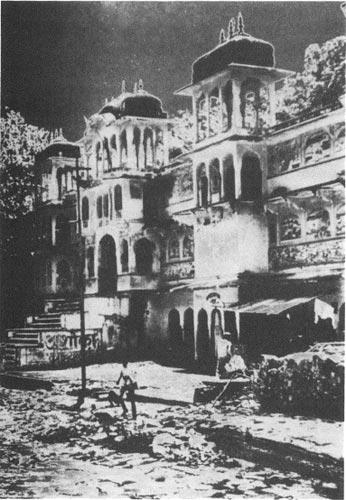

The palace of Galta (18th century), (photograph by Eusebio Rojas).

In this liturgical sequence there are ten divinities, ten oblations, ten restitutions, ten portions of the group of the sacrifice, and the Poem in which it is said consists of stanzas of verses of ten syllables. The Poem is none other than Splendor.

(Satapatha-Brahmana

, 11-4-3)

The word

The word

reconciliation

appears and reappears. For a long time I lighted my way with it, I ate and drank of it.

Liberation

was its sister and its antagonist. The heretic who abjures his errors and returns to the bosom of the church is reconciled with it; the purification of a sacred place that has been profaned is a reconciliation. Separation is a lack, an aberration. A lack: something is missing, we are not whole; an aberration: we have gone astray, we are not in the place where we belong. Reconciliation unites what was separated, it transforms the exclusion into conjunction, it reassembles what has been dispersed: we return to the whole and thus we return to the place where we belong. The end of exile. Liberation opens up another perspective: the breaking of chains and bonds, the sovereignty of free will. Conciliation is dependence, subjection; liberation is self-sufficiency, the plenitude of the one, the excellence of the unique. Liberation: being put to the proof, purgation, purification. When I am alone I am not alone: I am with myself; being separated is not being excluded: it is being oneself. When with everyone, I am exiled from myself; when I am alone, I am in the whole that belongs entirely to me. Liberation is not only an end of others and of otherness, but an end of the self. The return of the self—not to itself: to what is the same, a return to sameness.

Is liberation the same as reconciliation? Although reconciliation leads by way of liberation and liberation by way of reconciliation, the two paths meet only to divide again: reconciliation is identity in concord, liberation is identity in difference. A plural unity; a selfsame unity. Different, yet the same; precisely one and the same. I am the others, my other selves; I in myself, in selfsameness. Reconciliation passes by way of dissension, dismemberment, rupture, and liberation. It passes by and returns. It is the original form of revolution, the form in which society perpetuates itself and re-engenders itself: regeneration of the social compact, return to the original plurality. In the beginning there was no One: chief, god, I; hence revolution is the end of the One and of undifferentiated unity, the beginning (re-beginning) of variety and its rhymes, its alliterations, its harmonious compositions. The degeneration of revolution, as can be seen in modern revolutionary movements, all of which, without exception, have turned into bureaucratic caesarisms and institutionalized idolatry of the Chief and the System, is tantamount to the

decomposition

of society, which ceases to be a plural harmony, a

composition

in the literal sense of the word, and petrifies in the mask of the One. The degeneration lies in the fact that society endlessly repeats the image of the Chief, which is nothing other than the mask of

discomposure:

the disconcerting excesses, the imposture of the Caesar. But there never is a one, nor has there ever been a one: each one is an everyone. But there is no everyone: there is always one missing. We are neither a one together, nor is each all. There is no one and no all: there are ones and there are alls. Always in the plural, always an incomplete completeness, the

we

in search of its each one: its rhyme, its metaphor, its different complement.

I felt separated, far removed—not from others and from things, but from myself. When I searched for myself within myself, I did not find myself; I went outside myself and did not discover myself there either. Within and without, I always encountered another. The same self but always another self. My body and I, my shadow and I, their shadow. My shadows: my bodies: other others. They say that there are empty people: I was full, completely full of myself. Nonetheless, I was never in complete possession of myself, and I could never get all the way inside myself: there was always someone else there. Should I do away with him, exorcise him, kill him? The trouble was that the moment that I caught sight ofhim, he vanished. Talk with him, win him over, come to some agreement? I searched for him here and he turned up there. He had no substance, he took up no space whatsoever. He was never where I was; if I was there he was here; if I was here he was there. My invisible foreseeable, my visible unforeseeable. Never the same, never in the same place. Never the same place: outside was inside, inside was somewhere else, here was nowhere. Never anywhere. Great distances away: in the remotest of places: always way over yonder. Where? Here. The other has not moved: I have never moved from my place. He is here. Who is it that is here? I am: the same self as always. Where? Inside myself: from the beginning I have been falling inside myself and I still am falling. From the beginning I am always going to where I already am, yet I never arrive at where I am. I am always myself somewhere else: the same place, the other I. The way out is the way in: the way in—but there is no way in, it is all the way out. Here inside is always outside, here is always there, the other always somewhere else. There is always the same: himself: myself: the other. I am that one: the one there. That is how it is; that is what I am.

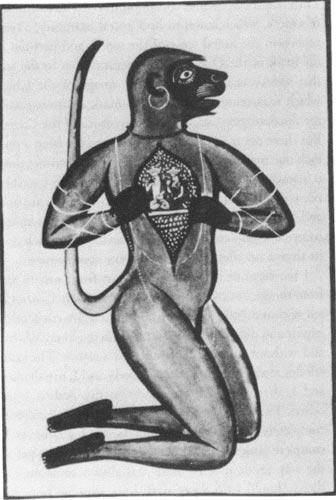

Hanum n, Kalighat painting (Bengal), 20th century.

n, Kalighat painting (Bengal), 20th century.