The Monkey Grammarian (12 page)

With whom could I reconcile myself: with myself or with the other—the others? Who were they, who were we? Reconciliation was neither an idea nor a word: it was a seed that, day after day at first and then hour after hour, had continued to grow and grow until it turned into an immense glass spiral through whose arteries and filaments there flowed light, red wine, honey, smoke, fire, salt water and fresh water, fog, boiling liquids, whirlwinds of feathers. Neither a thermometer nor a barometer: a power station that turns into a fountain that is a tree with branches and leaves of every conceivable color, a plant of live coals in winter and a plant of refreshing coolness in summer, a sun of brightness and a sun of darkness, a great albatross made of salt and air, a reflection-mill, a clock in which each hour contemplates itself in the others until it is reduced to nothingness. Reconciliation was a fruit—not the fruit but its maturity, not its maturity but its fall. Reconciliation was an agate planet and a tiny flame, a young girl, in the center of that incandescent marble. Reconciliation was certain colors interweaving so as to form a fixed star set in the forehead of the year, or floating in warm clusters between the spurs of the seasons; the vibration of a particle of light set in the pupil of the eye of a cat flung into one corner of noon; the breathing of the shadows sleeping at the foot of an autumn skinned alive; the ocher temperatures, the gusts of wind the color of dates, a yellowish red, and the green pools of stagnant water, the river basins of ice, the wandering skies dressed in regal rags, the drums of the rain; suns no bigger than a quarter of an hour yet containing all the ages; spiders spinning translucent webs to trap infinitesimal blind creatures that emit light; foliage of flames, foliage of water, foliage of stone, magnetic foliage. Reconciliation was a womb and a vulva, but also the blinks of an eye, provinces of sand. It was night. Islands, universal gravitation, elective affinities, the hesitations of the light that at six o’clock in the late afternoon does not know whether to go or to stay. Reconciliation was not I. It was not all of you, nor a house, nor a past or a future. It was there over yonder. It was not a homecoming, a return to the kingdom of closed eyes. It was going out into the air and saying:

good morning

.

The wall was about two hundred yards long. It was tall, topped with parapets. Save for certain stretches that still showed traces of blue and red paint, it was covered with huge black, green, and dark purple spots: the fingerprints of the rains and the years. Just below the parapets, in a horizontal line running the length of the wall, a series of little balconies could be seen, each one crowned with a dome mindful of a parasol. The wooden blinds were faded and eaten away by the years. Some of the balconies still bore traces of the designs that had decorated them: garlands of flowers, branches of almond trees, little stylized parakeets, seashells, mangoes. There was only one entrance, an enormous one, in the center: a Moorish archway, in the form of a horseshoe. It had once been the elephant gateway, and hence its enormous size was completely out of proportion to the dimensions of the group of buildings as a whole. I took Splendor by the hand and we crossed through the archway together, between the two rows of beggars on either side. They were sitting on the ground, and on seeing us pass by they began whining their nasal supplications even more loudly, tapping their bowls excitedly and displaying their stumps and sores. With great gesticulations a little boy approached us, muttering something or other. He was about twelve years old, incredibly thin, with an intelligent face and huge, dark, shining eyes. Some disease had eaten away a huge hole in his left cheek, through which one could see some of his back teeth, his gums, and redder still, his tongue, moving about amid little bubbles of saliva—a tiny crimson amphibian possessed by a raging, obscene fit of agitation that made it circle round and round continuously inside its damp grotto. He babbled on endlessly. Although he emphasized his imperious desire to be listened to with all sorts of gestures and gesticulations, it was impossible to understand him since each time he uttered a word, the hole made wheezes and snorts that completely distorted what he was saying. Annoyed by our failure to understand, he melted into the crowd. We soon saw him surrounded by a group of people who began praising his tongue-twisters and his sly ways with words. We discovered that his loquacity was not mere nonsensical babble: he was not a beggar but a poet who was playing about with deformations and decompositions of words.

The wall was about two hundred yards long. It was tall, topped with parapets. Save for certain stretches that still showed traces of blue and red paint, it was covered with huge black, green, and dark purple spots: the fingerprints of the rains and the years. Just below the parapets, in a horizontal line running the length of the wall, a series of little balconies could be seen, each one crowned with a dome mindful of a parasol. The wooden blinds were faded and eaten away by the years. Some of the balconies still bore traces of the designs that had decorated them: garlands of flowers, branches of almond trees, little stylized parakeets, seashells, mangoes. There was only one entrance, an enormous one, in the center: a Moorish archway, in the form of a horseshoe. It had once been the elephant gateway, and hence its enormous size was completely out of proportion to the dimensions of the group of buildings as a whole. I took Splendor by the hand and we crossed through the archway together, between the two rows of beggars on either side. They were sitting on the ground, and on seeing us pass by they began whining their nasal supplications even more loudly, tapping their bowls excitedly and displaying their stumps and sores. With great gesticulations a little boy approached us, muttering something or other. He was about twelve years old, incredibly thin, with an intelligent face and huge, dark, shining eyes. Some disease had eaten away a huge hole in his left cheek, through which one could see some of his back teeth, his gums, and redder still, his tongue, moving about amid little bubbles of saliva—a tiny crimson amphibian possessed by a raging, obscene fit of agitation that made it circle round and round continuously inside its damp grotto. He babbled on endlessly. Although he emphasized his imperious desire to be listened to with all sorts of gestures and gesticulations, it was impossible to understand him since each time he uttered a word, the hole made wheezes and snorts that completely distorted what he was saying. Annoyed by our failure to understand, he melted into the crowd. We soon saw him surrounded by a group of people who began praising his tongue-twisters and his sly ways with words. We discovered that his loquacity was not mere nonsensical babble: he was not a beggar but a poet who was playing about with deformations and decompositions of words.

The main courtyard was a rectangular esplanade that had surely been the outdoor “audience chamber,” a sort of hall outside the palace itself, although within the walls surrounding it, in which the princes customarily received their vassals and strangers. Its surface was covered with loose dirt; once upon a time it had been paved with tiles the same pink color as the walls. The esplanade was enclosed by walls on three sides: one to the south, another to the east, and another to the west. The one to the south was the Gateway through which we had entered; the other two walls were not as long and not as high. The one to the east was also topped with a parapet, whereas the one to the west had a gable-end roofed over with pink tiles. Like the Gateway, the entryway let into both the other walls was an arch in the form of a horseshoe, although smaller. Along the east wall” there was repeated the same succession of little balconies as on the outer face of the Gateway wall, all of them also crowned with parasol domes and fitted out with wooden blinds, most of which had fallen to pieces. On days when the princes received visitors, the women would conceal themselves behind these blinds so as to be able to contemplate the spectacle below without being seen. Opposite the main wall, on the north side of the quadrangle, was a building that was not very tall, with a stairway leading to it which, despite its rather modest dimensions, nonetheless had a certain secret stateliness. The ground floor was nothing more than a massive cube of mortar, with no other function than to serve as a foundation for the upper floor, a vast rectangular hall bordered on all sides by an arcade. Its arches reproduced, on a smaller scale, those of the courtyard, and were supported by columns of random shapes, each one different from the others: cylindrical, square, spiral. The structure was crowned by a great many small cupolas. Time and many suns had blackened them and caused them to peel: they looked like charred, severed heads. From time to time there came from inside them the sound of parakeeets, blackbirds, bats, making it seem as though these heads, even though they had been lopped off, were still emitting thoughts.

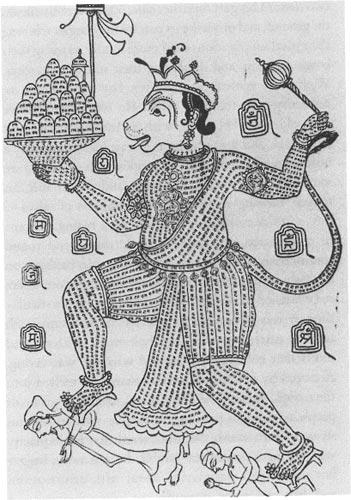

Hanum n, Rajasthan, 20th century.

n, Rajasthan, 20th century.

The whole was theatrical, mere show. A double fiction: what those buildings represented (the illusions and nostalgias of a world that no longer existed) and what had been staged within their walls (ceremonies in which impotent princes celebrated the grandeur of a power on the point of ceasing to exist). An architecture in which to see oneself living, a substitution of the image for the act and of myth for reality. No, that is not precisely it. Neither image nor myth: the rule of obsession. In periods of decadence obsession is sovereign and takes the place of destiny. Obsession and its fears, its cupidity, its phobias, its monologue consisting of confessions-accusations-lamentations. And it was precisely this, obsession, that redeemed the little palace from its mediocrity and its banality. Despite its mannered hybridism, these courtyards and halls had been inhabited by chimeras with round breasts and sharp claws. A novelistic architecture, at once chivalrous and over-refined, perfumed and drenched with blood. Vividly lifelike and fantastic, chaotic and picturesque, unpredictable. A passionate architecture: dungeons and gardens, fountains and beheadings, an eroticized religion and an esthetic eroticism, the n yik

yik ’s hips and the limbs of the quartered victim. Marble and blood. Terraces, banquet halls, music pavilions in the middle of artificial lakes, bedroom alcoves decorated with thousands of tiny mirrors that divide and multiply bodies until they become infinite. Proliferation, repetition, destruction: an architecture contaminated by delirium, stones corroded by desire, sexual stalactites of death. Lacking power and above all time (architecture requires as its foundation not only a solid space but an equally solid time, or at least capable of resisting the assaults of fortune, but the princes of Rajasthan were sovereigns doomed to disappear and they knew it), they erected edifices that were not intended to last but to dazzle and fascinate. Illusionist castles that instead of vanishing in this air rest on water: architecture transformed into a mere geometric pattern of reflections floating on the surface of a pool, dissipated by the slightest breath of air…. There were no pools or musicians on the great esplanade now and no n

’s hips and the limbs of the quartered victim. Marble and blood. Terraces, banquet halls, music pavilions in the middle of artificial lakes, bedroom alcoves decorated with thousands of tiny mirrors that divide and multiply bodies until they become infinite. Proliferation, repetition, destruction: an architecture contaminated by delirium, stones corroded by desire, sexual stalactites of death. Lacking power and above all time (architecture requires as its foundation not only a solid space but an equally solid time, or at least capable of resisting the assaults of fortune, but the princes of Rajasthan were sovereigns doomed to disappear and they knew it), they erected edifices that were not intended to last but to dazzle and fascinate. Illusionist castles that instead of vanishing in this air rest on water: architecture transformed into a mere geometric pattern of reflections floating on the surface of a pool, dissipated by the slightest breath of air…. There were no pools or musicians on the great esplanade now and no n yik

yik s were hiding on the little balconies: that day the pariahs of the Balmik caste were celebrating the feast of Hanum

s were hiding on the little balconies: that day the pariahs of the Balmik caste were celebrating the feast of Hanum n, and the unreality of that architecture and the reality of its present state of ruin were resolved in a third term, at once brutally concrete and hallucinatory.

n, and the unreality of that architecture and the reality of its present state of ruin were resolved in a third term, at once brutally concrete and hallucinatory.