The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (36 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Other spots in and outside the basin have been selected, and the topic is often animated among tourists. Such speculation can have little relevance to the matter considered in these pages. Whether there was or was not an appropriate spot in the basin for the casting down does not add to our evidence of a settlement at Nazareth in the time of Jesus. As regards the account in scripture, there are many problems associated with the authenticity of the Lucan pericope (which Bultmann showed was a rewriting of Mark),

[512]

quite outside topographical considerations.

A synagaogue of the first century

CE

?

From the foregoing review of the movable and structural evidence in the basin, it is clear that the presence of an imposing manmade structure dating to the turn of the era is an impossibility. As shown above, we have no oil lamps from the alleged time of Jesus, no pottery, no tombs, no coins, and so on. The frequent allusions to a synagogue at Nazareth in Early Roman times must rest entirely on extra-archaeological considerations, namely, on the gospel accounts, most particularly that of Luke (4:16

ff

.).

Despite the above, claims have been made for not one, but

two

synagogues in Roman Nazareth. This complexity is an unforeseen result of the Church’s longstanding desire to authenticate its presence at Nazareth. That desire led to the thesis that Jewish Christians lived in Nazareth continuously from apostolic times. However, it soon became evident that

minim

would not have been welcome in Jewish synagogues, as the Gospel of John already makes clear:

“Ask him; he is of age, he will speak for himself.” His parents said this because they feared the Jews, for the Jews had already agreed that if any one should confess him to be Christ, he was to be put out of the sysagogue. (Jn 9:22;

pre-70

12:42–43)

Thus, the tradition proposed one synagogue for the Jewish Christian followers of Jesus, and another one for the Jews. Bagatti suggests that the former was under the Church of the Annunciation itself (

Exc

. 145–46). He duly notes signs of a Byzantine ecclesiastical structure there, and then suggests “Pre-Byzantine buildings” of the second to fourth centuries CE. “Other chronological considerations,” he writes, “will be derived from the graffiti.” However, Taylor has shown that neither the masonry evidence nor the graffiti are earlier than IV CE.

[513]

In another passage (

Exc

. 111) Bagatti suggests that “high bases [

of

columns

] were reused because they are of the same kind as the stones found under the mosic pavement of which we shall speak.” Here again, however, the mosaic is of a late date (V CE), and the stones under it belong to the first ecclesiastical structure constructed in IV CE. Bagatti suggests that the stylobate wall between the nave and the southern aisle of the basilica was reused in the Byzantine church (

Exc

. 84–85, 115), but this wall also certainly formed part of the IV CE construction. Finally, the Italian suggests that two marble columns were part of the early structure, but Taylor writes that these belong to “relatively modern masonry.” She notes that the original structure had an east-facing apse, and that “synagogues were oriented toward Jerusalem and churches to the east.” “The form of the building ...bears no resemblance whatsoever to a synagogue. It is an unconventional structure designed to encompass the cave complex in a practicable manner.”

[514]

Bagatti’s second synagogue, “that of the Jews” (

Exc

. 233–34) was located about 150 m northwest of the Church of St. Joseph. Indeed, there is evidence that such a structure existed in later Roman and/or Byzantine times, one which served the Jewish population of Nazareth. The structure was converted to Christian use after the Jews were expelled in the seventh century.

[515]

Four column bases of white calcite were found at this location (

Exc

. 233). There are Hebrew mason’s markings of a

lamed

,

dalet

, final

mem

and a

tet

which is “curiously more similar to Nabataean than the usual Jewish script” (Taylor). Interestingly, the arguable presence of Nabatean has led some to propose an Early Roman dating for the columns and hence for the entire synagogue (on the false basis that Nabatean script was necessarily early, or even decisive in this case). However, there is no reason to suppose that the columns, and the Jewish synagogue that once stood at the site, predated Byzantine times.

The neighborhood of Nazareth

For completeness, mention can be made of two tombs not far from the Nazareth basin but outside the scope of this study. One is located 2.3 km NE of the Church of the Annunciation, on the far side of the Jebel en-Namsawi (peak 500 m). The only published material on this excavation is a half-page article titled “Nazareth.”

[516]

At least fourteen kokhim were revealed, together with a quantity of pottery (including “Herodian” lamps) which the authors—A. and N. Najjar—attribute to “the 1st century CE.” No itemization is offered, and I have made no attempt to verify the dating of this tomb, for it probably came within the ambit of the settlement of Hirbet Tirya.

Those responsible for hewing the foregoing tomb may also have used a tomb complex 2.6 km east of the CA, excavated by Nurit Feig in 1981 and also considerably outside the Nazareth basin.

[517]

I have studied the results of the four Feig tombs which—though damaged and robbed in ancient times—divulged a considerable quantity of artefacts, including a number of bow-spouted oil lamps. Ms. Feig dates the complex to “between the middle of the first century and the third century A.D.” (p. 79). This entirely accords with the archaeological results from the basin, and shows that material remains in a wider radius from the CA were contemporaneous with the settlement of Nazareth. It is entirely possible that these more distant tombs were also connected with the people who settled Nazareth in the latter half of I CE, or with their descendants.

[518]

Conclusions

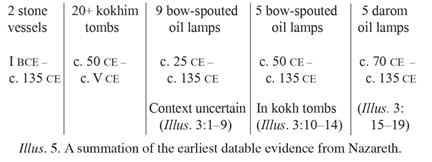

Taking scripture as their guide, most scholars reflexively assume that Nazareth existed in I BCE and—in all likelihood—also in Hellenistic times. Few have given the matter much thought, preferring instead to defer to reputed experts who, as we have seen, have been less than honest with the data of archaeology. Both expert and non-specialist scholar have danced to the same piper, cleaving to the scriptures that they hold dear. The evidence in the ground, however, clearly contradicts those ancient writings. We can now affirm that

not a single post-Iron Age artefact, tomb or structure at Nazareth dates with certainty before 100 CE

.

The critical oil lamp information, collated above, shows that human presence in the basin postdated

c

. 25 CE. The beginning of kokh tomb use in the Galilee (

c

. 50 CE) further demonstrates that the settlement came into being not before the middle of the first century of our era.

[519]

All the other evidence, both movable and structural, is compatible with a beginning of settlement in the years following the First Jewish Revolt.

The nineteen bow-spouted oil lamps from Nazareth—the earliest post-Iron Age lamps from the basin (above,

Illus

.

4.3

)—can all be dated between the two Jewish revolts. A number of them (the Darom lamps)

must

be so dated. Hence, the decades between the two Jewish revolts are the earliest in which we can speak with certainty of the reappearance of people in the basin. Before 70 CE such presence is questionable. Certainly, the possibility exists that some settlers came into the basin as early as 25 CE. This view, however, requires that we abandon an impartial stance regarding the evidence and adopt an “early” scenario.

We have seen that the label “Herodian” has caused great damage. It has been misapplied both to oil lamps and tombs, with the result that much later evidence has been insinuated into the time of Herod the Great. This “backdating” of evidence is pervasive in the Nazareth literature.

Two stone vessels could be dated to I BCE, and the first oil lamps as early as

c

. 25 BCE—but all of these ‘earliest’ Roman artefacts, without exception, could equally well date as late as II CE. We shall see (Chapter 6) that the great bulk of Roman evidence dates to the second century CE and thereafter.

Given the fact that it takes a generation or two to establish a village, it is certainly not possible to envisage a named settlement of Nazareth (Semitic

Natsareth

) before 70–135 CE. The approximate midpoint of this range is 100 CE, and that is the date I suggest for the beginning of the “village” of Nazareth as a named place. Though people may have begun to enter the basin a generation or two earlier, we cannot speak with confidence of a village before the second century of our era. This is the only reasonable conclusion to be derived from an impartial view of the evidence.

Of course, this analysis turns prior theories of the genesis of Nazareth on their head:

First-century Nazareth was a small Jewish settlement with no more than two to four hundred inhabitants. Like the rest of Galilee, which lay relatively uninhabited until the Late Hellenistic Period, Jews settled it under Hasmonean

expansionist policies.

[520]

We can now affirm that the settlement of Nazareth was much later than the period of the Hasmoneans. It was indeed Jews who settled the basin, but they did so towards the end of the first century of our era, following the momentous cataclysm of the First Jewish War.

Chapter Five

Gospel Legends

The location and size of the ancient village

Competing literary traditions

The traditional view regarding the location of Nazareth in Jesus’ day rests on three fundamental errors: (1) that habitations existed on the hillside known today as the Nebi Sa‘in; (2) that one of those habitations, now under Church of the Annunciation, was the maiden home of the Virgin Mary; and (3) that the residential portion of the village lay higher up the slope.

All these beliefs are ancient, and they ultimately stem from the localization of Mary’s dwelling in the present venerated area, which measures approximately 100 by 60 m. As early as IV CE the spot was marked by a small Christian edifice.

[521]

The Roman Catholic Church has maintained that tradition ever since. We may ask: why was this inauspicious site identified with Mary’s maiden dwelling? The area, after all, was hardly appropriate for dwellings until modern times, being rocky, cavernous, and sloping (see below).

[522]

In answer to that question, we note that the first Christian pilgrims to Nazareth apparently associated the humble dwelling of Mary with a cave, of which there are many on the hillside.

[523]

We should not demand logic from such associations, which derive from piety and thrive largely outside the realm of reason. Perhaps, in locating Mary’s dwelling in a cave (or contiguous to one), the original tradition conflated her dwelling with the nativity scene in the cave of Bethlehem (Lk 2:7

ff

). Both have merged in the pilgrim’s mind, as in this Medieval account:

Then we went to Nazareth… There beside the city is the site of the Annunciation, and this is an underground cave, which is very like that of Bethlehem

where Christ was born…

[524]

In pious traditions such a conflation of elements is not rare. For example, today the Christmas story juxtaposes Matthew’s magi and Luke’s shepherds. In choosing a cave for the Annunciation, the early pilgrims were perhaps also influenced by the humility of Mary, for which the simple setting of a cave is uniquely appropriate. In any case, today the alleged domicile of Mary lies in the “venerated grotto,” at the lowest level of the Church of the Annunciation (CA). At the mouth of that cave is a modest area measuring 5×10 m known as the Chapel of the Angel. There the angel Gabriel spoke to the virgin.

[525]