The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus (40 page)

Read The Myth of Nazareth: The Invented Town of Jesus Online

Authors: Rene Salm

Approximately a decade later, however, Strange arrived at a radically different solution:

As inferred from the Herodian tombs in Nazareth, the maximum extent of the Herodian and pre-Herodian village measured about 900×200 m, for a total area just under 60 acres. Since most of this was empty space in antiquity, the population

would have been a maximum of about 480 at the beginning of the 1

st

century A.D.

[565]

Several elements of this passage are noteworthy. First of all, “900×200 m” measures an area equivalent to just under 45 acres (44.48 acres = 18 hectares),

[566]

not 60 acres. Secondly, the area Strange now proposes for habitation is many times larger than his 1981 estimate (180,000 square meters

vs

. 40,000 square meters), yet it is still only one half the habitable area of the valley floor as inferred above. Thirdly, the archaeological remains offer no clue at all as to how much “empty space” there may have been in antiquity. The only area systematically excavated has been the venerated area, which measures under one hectare, not the 18 hectares that Strange implies. It is a complete mystery how, from the modest area that has been excavated, he can arrive at “a maximum of about 480” people for the entire village. We also note that though the area he now considers for habitation is over four times larger than in 1981, his population estimate is four times smaller (“1,600 to 2,000” vs. 480). Finally, we are at a complete loss as to how Strange links his population estimate to “the beginning of the 1

st

century A.D.” All this might be of little consequence were Strange not the most cited archaeologist on Nazareth of the last generation, and were his 1992 ABD article not the first (and often only) scholarly source for information about Nazareth.

In the above two citations, Strange has insisted upon precision where Bagatti was originally much more cautious:

Limits of the ancient village. – By observing the common rule which excluded tombs from places of habitation, one arrives, by the discovery of sepulchral chambers, at delimiting in some sense the extent of the ancient village.

[567]

This passage is from the Italian’s article “Nazareth” in the

Dictionnaire de la Bible

, written midway in his excavation of the venerated area. In principle, Bagatti is entirely correct. One can, through the emplacement of the tombs, delimit “in some sense the extent of the ancient village.” In fact, this is what we have done above, and we have seen that the village was

on the valley floor

. We have determined this by considering all the tombs in the basin, including those to the east, and by also taking into account the character of the hillsides.

Though Bagatti’s affirmation above is correct in principle, its application amounts to nonsense, for the archaeologist thinks that the venerated area was itself part of the ancient village, which stretched astride the mountain. We have critiqued the questionable “ring of tombs” that he, Kopp, and others propose on the hillside, and from which they think to delimit a village. That location defends the idea that the venerated area was the site of Jesus’ home. That idea, in turn, ultimately derives from the fourth chapter of Luke, where Nazareth is located on “the brow of a mountain upon which their city had been built.”

[568]

This notion was already very familiar to the first pilgrims. Indeed, it was probably their only “hard” fact about Nazareth. Yet, where exactly on the hillside the Holy Family lived was for a long time in dispute—and still is. We have seen that there are dual traditions. The Greek Orthodox follow the

Protevangelium of James

and locate the dwelling of Mary over the spring at the north of the basin. This seems to have been the earliest tradition.

For example, the sixth-century visitor known as the Anonymous of Piacenza supposed that the spring had to be “in the middle of the city.”

In the 1930s, the redoubtable Fr. Clemens Kopp attempted to harmonize these competing traditions. Seeing that the Roman Church venerated an area at some remove from the spring, yet at the same time acknowledging the more ancient tradition, Kopp proceeds from the assumption that the town was indeed centered at the spring and extended as far as the Franciscan venerated area:

The two basilicas are separated from one another by a [

substantial

] distance. That over the spring is “in the middle of the city,” that of the Annunciation must then, to avoid contradiction, have lain either outside the settlement or on its rim… As has been already mentioned, Jewish Nazareth must—on account of the graves [

under the Franciscan

venerated

area

]—have been situated at the spring. Presumably it moved from thence southwards along the western side of the valley, reaching the [

present-day

] Moslem cemetery, since according to well-attested tradition it was here that in 570 the synagogue

[

noted by the

] Anonymous of Piacenza

stood.

[569]

Thus, Kopp again proposes that Nazareth moved. We recall his mobile Nazareth hypothesis relating to the Bronze and Iron Ages. This later movement permits accommodation of the two traditions, one centered about the spring, the other about the venerated area. Of course, his argument completely ignores the valley floor, the unwelcome topography of the slope, as well as the presence of tombs on the other side of the valley—tombs which Kopp himself mapped. The

raison d’être

of Kopp’s argument is to accommodate the Franciscan zone on the hillside. We shall now examine more closely that zone, and why it could not have been the dwelling place of Mary, Jesus, and Joseph.

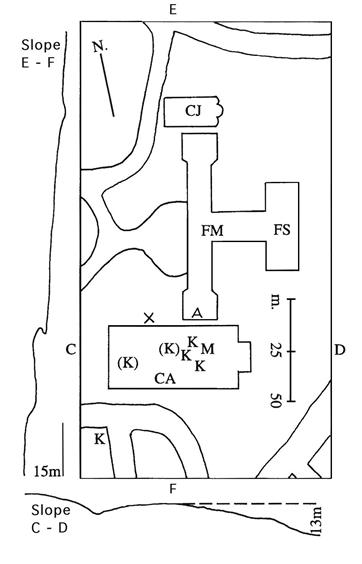

The venerated area

The area owned by the Custodia di Terra Santa, an arm of the Roman Catholic Franciscan order, has been the locus of most of the archaeological work in the Nazareth basin and is of necessity the focus of this study. The visitor today will find the venerated area situated in a densely populated urban area. Since 1620 CE (when the Druse emir Fakr ed-Din permitted Christians back into Nazareth) the Franciscans have owned a roughly triangular plot of land 100×150 m at its greatest extent, on which are now several structures: (1) the Church of the Annunciation (CA) to the south; (2) the Church of St. Joseph (CJ) to the north; (3) the long Franciscan monastery between them; and (4) the monastery school (

Illus

.

5.3

). Bagatti’s excavations in the decade from 1956–66 were focused on the southern portion lying under and around the CA (the convent and CJ were already standing). The results of those excavations are described in the archaeologist’s two-volume

Excavations in Nazareth

.

In the following pages, measurements will be computed from the nearest wall of the Church of the Annunciation. Thus, Mary’s Well is 800 m northeast of the CA, and Tomb 70 is 30 m south of the CA.

[570]

The slope

The eastern side of the Nebi Sa‘in rises from 320m at the valley floor to a peak of 495 m, an average grade of 14%—steep by any account. The sections to the left and below

Illus

.

5.3

depict the slope of the venerated area and are redrawn from Bagatti’s

Excavations in Nazareth

(Plate XI). According to the diagram, the average slope of the venerated area from north to south is 8%, but the archaeologist describes a somewhat steeper grade in the text:

As for the nature of the terrain, now that we are at the level of the rock a steep incline from north to south is noted (9.8m within the excavated area of 70 m), which continues towards the north, resulting in

c

. 14 m of difference with the Church of St. Joseph. Roughly the same steep incline exists to both east and west…

[571]

“9.8 m within the excavated area of 70 m” is equivalent to a 14% grade—similar to that of the hillside in general. This information places a curious passage of Kopp in relief:

Before the slope, running southwards from [

the

] Nebi Sa‘in on the north, comes to an end in the valley, there is a fairly level rock plateau. Here the Church of the Annunciation

stands.

Photograph courtesy of gallery.tourism.gov.il

Photograph of the modern Roman Catholic Church of the Annunciation, apparently the fifth shrine to be built at this location. Believed by many to mark the home of the Virgin Mary and the place where the Archangel Gabriel delivered the original ‘Hail Mary,’ the church is built over tombs of an ancient necropolis.

Illus. 5.3.

The

venerated area.

The slope of the hill is given in section to the left (north-south A–B) and below the diagram (east-west C–D). Principal modern streets are indicated.

CA = Ch. of the Annunciation CJ = Ch. of St. Joseph

FM = Franciscan Monastery FS = Franciscan school

K = kokhim tomb M = alleged house of Mary

A = “The Virgin’s Kitchen”

X = Possible habitation of the Holy Family according to Viaud

“A fairly level rock plateau” is scarcely an appropriate designation for the venerated area. The difference in elevation, for example, between the two ends of the Franciscan Monastery is roughly 10 m. This caused problems during the building’s construction in 1930. The entryway of the small Church of St. Joseph (CJ), first built V–VI CE,

[572]

is 3 m higher than the foundation of its apse at the eastern end (see

Illus

.

5.5

). Of course, the floor of the CJ rests on a built up foundation which masks the underlying slope of the hillside.

[573]

This is the spot where tradition locates the “Workshop of St. Joseph,” and in Roman Catholic tradition it is the place where Jesus was reared (“House of the Nutrition”). As for the Church of the Annunciation, we see from

Illus

.

5.3

that the terrain under the eastern half of the edifice slopes severely, and indeed possesses the remarkable grade of 24%. It is a most unlikely spot for ancient habitations, unless we credit the rural Jews of Roman times with modern engineering skills or suppose that Mary’s home (“M” in

Illus

.

5.3

) was tilted, as also Joseph’s residence 100 m to the north.

[574]

The ancient Nazarenes did not have concrete and steel girders, nor modern construction and engineering techniques for erecting edifices on slopes. Nor is there any evidence that these folk laboriously cut into the side of the Nebi Sa‘in to make flat areas on the hillside on which to build their dwellings. Finally, we are left with the obvious question: why would they not choose the valley floor on which to settle? We cannot suppose reasons of defense weighed in this, for living halfway up the hill is hardly a safer proposition in case of attack.