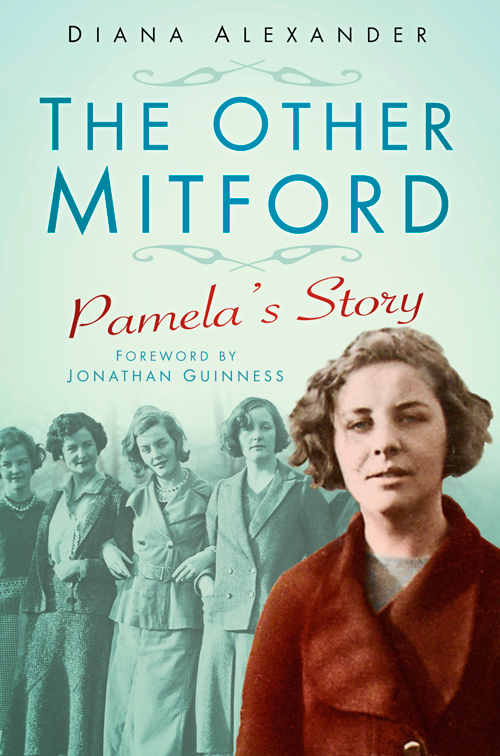

The Other Mitford

Authors: Diana Alexander

For Malcolm who has constantly encouraged me in this project.

For Kate and Emily, who knew and loved Pam, and for Daisy and Ruby who would have loved her had they known her.

I should like to thank: Jonathan Guinness, Lord Moyne, for his help and encouragement and for writing the foreword to this book; Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, for allowing me to use the Mitford Archive photographs and Helen Marchant for arranging this; Max Mosley and Lady Emma Tennant for talking to me about their much-loved aunt; and Dee Hancock for her unstinting interest and valuable information. Also the many other people who have so willingly contributed to this book. These include: William Cooper, Christopher Fear, Celia Fitzpatrick, Stephen and Freddie Freer, Lorna Gray, Julian Leeds, Pat Moodie, George and Margrit Powell, Guy Rooker, Michael Russell, Joan Sadler, Pat Saunders, Deirdre Waddell and Christine Whitaker.

I could not have written

The Other Mitford

without reference to the following books about the Mitford family:

The House of Mitford

by Jonathan Guinness,

Letters Between Six Sisters

edited by Charlotte Mosley,

The Mitford Sisters

by Mary Lovell,

Wait for Me

by Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire and

As I was going to St Ives: A Life of Derek Jackson

by Simon Courtauld

One | |

Two | |

Three | |

Four | |

Five | |

Six | |

Seven | |

Eight | |

Nine | |

Ten | |

Eleven | |

Twelve | |

Thirteen | |

Fourteen | |

Fifteen | |

Sixteen | |

Seventeen | |

Eighteen | |

Nineteen | |

by Jonathan Guinness

‘T

his is my sister Pam,’ said Deborah Devonshire as I introduced a friend to them both. ‘She’s just back from Switzerland and she can tell you the menu of every meal she’s had on the way.’ For Pam was legendary for never forgetting food. Her symbol in Charlotte Mosley’s collection of the six sisters’ letters, corresponding to Unity’s swastika, Jessica’s hammer and sickle and so on, is crossed spoons. Perhaps this was the occasion when Pam had brought to Chatsworth in her luggage a dozen eggs which when hatched would grow into the elegantly coiffed Appenzeller Spitzhaube chickens which were then new to this country.

Until now Pam has been the only one of the six Mitford sisters not to be the subject of a book to herself, and in filling this gap Diana Alexander has, as it were, earthed the Mitford story. ‘My wife is normal,’ wailed Lord Redesdale. ‘I am normal, but my daughters are all off their heads.’ Well, not all, actually. Pam could run a farm or a household to perfection: she coped for thirteen years with a millionaire husband who was physics professor, steeplechase jockey, and air ace but also dangerously mercurial and liable to behave outrageously. Their marriage broke up but he retained deep fondness for her through four later marriages, leaving her a fortune in his will.

In managing Derek, Pam perhaps benefitted from having suffered from Nancy as her older sister. For Nancy was an accomplished tease and Pam, as next oldest, was the one who bore the brunt. But Nancy was also very funny, and what Pam and the others all learned was to ride with the punch, to enjoy the jokes without being too upset by the unkindness.

Pam’s childhood polio certainly set her back educationally, but I’m not sure she was dyslexic. If so, it was a very mild case. She was a rather erratic speller, but so was Evelyn Waugh. She was not as avid a reader as the others, but

Tales of Old Japan

was not the only one of her Redesdale grandfather’s books she absorbed: she knew them all, including his substantial

Memories

. She learned German without having a single lesson and spoke it well enough to guide Nancy through East Germany when Nancy was researching her biography of Frederick the Great.

What I most respected in Pam was her love of the truth. When I told her I was intending to write the story of the Mitfords her first words were: ‘Yes: the real story, what actually happened.’ She was then endlessly helpful and her reminiscences, never in any way slanted, conveyed a sense of reality that took one back in time. It was this regard for truth that triggered an occasion mentioned in the

Letters

when Pam seems to have lost her temper, a rare event. Diana describes it in a letter to Deborah. Pam had been with Nancy and Jessica who had agreed with each other that the Mitford childhood was miserable. This, Pam had said indignantly, was quite untrue, and as she told the story to Diana she flushed and there were tears in her eyes.

Pam was always there when needed. She was staunch when Diana was clapped into Holloway without trial at what is supposed to have been Britain’s finest hour; she immediately took in Diana’s two babies and their Nanny. Then many years later, when Nancy was dying and all the sisters took turn at looking after her, it was always Pam whom she most wanted. When she herself was growing old, her many friends and relations loved the stories she told and her sense of humour, less sophisticated perhaps than that of her sisters, was always fun. Diana Alexander gives us a good taste of it.

S

o much has been written about the Mitford sisters, both by others and by themselves, that it would seem unlikely there is much left to say. It is incredible, therefore, that one of the sisters is still virtually unknown and there has certainly never been anything published in which she is the central figure – until now.

Pamela was the second of the six ‘Mitford Girls’ – a phrase coined by future poet laureate John Betjeman – and she had a tough childhood owing to the jealousy of her elder sister Nancy, who bitterly resented the new baby. Pamela had polio as a child which held back her physical progress; she was also probably dyslexic, a condition which was not recognised at the beginning of the twentieth century and was the reason why she was the only one of the sisters – apart from Unity, whose suicide attempt put paid to any authorship by her – who never wrote a book.

Pamela was a superb cook, a knowledgeable farmer and an imaginative gardener but, most important of all, she was the member of this extraordinary family who most resembled her mother, Lady Redesdale, whose mantle she gradually assumed, picking up the family pieces – and there were many – being there when help was needed and bringing the practical side of her nature to bear on the others’ problems.

Unlike most of the sisters she never espoused a cause, never brought any grief to her parents and, together with her youngest sister Deborah, was the only one who would have admitted to a happy childhood; and this was in spite of the treatment meted out to her by Nancy who also led the other siblings in the often cruel teasing. Of all the sisters she possessed the most contented personality. When, in the 1930s, the other ‘gels’ were forever in the news, Lady Redesdale once ruefully remarked: ‘Whenever I see a headline beginning “Peer’s daughter” I know it’s going to be about one of you children.’ But she wasn’t thinking of Pam.

This is not to say that Pam was in any way dull. Her humour was not as sharp but she loved hearing the others’ jokes; she could tell a funny story as well as anyone – usually about something which had happened to her – and her memory for past events (particularly meals) was legendary in the family. She never had any children but her nieces and nephews loved her because she never patronised them and was always ready to listen to what they had to say. In a strikingly good-looking family she more than held her own: she had the cornflower blue eyes inherited from the Mitford side and a face whose serenity not only reflected her personality but made her a close rival to Diana, always known as the beauty of the family. Although the others felt she was not as quick off the mark as they were, clever men were captivated by her. John Betjeman twice proposed to her and was twice rejected and she finally married Derek Jackson, one of the most eminent scientists of his generation, who also became a war hero and a successful amateur jockey. True, they were eventually divorced, but of his six wives she was married to him the longest and they became great friends after their divorce, even causing speculation among the sisters that they might remarry.

In spite of being rather shy, Pam possessed a tremendous spirit of adventure. During the year she spent in France she had a ride in a tank, which she declared was much more exciting than any of the social events to which she was invited and wished she could do it all over again, and during the 1930s she motored alone all over Europe.

Shortly after her marriage to Derek she became one of the first women to fly across the Atlantic in a commercial aircraft, taking it all in her stride. Prior to that she had enjoyed gold-prospecting with her parents in Canada (although this was never a successful enterprise) and later had managed the farm belonging to Bryan Guinness, Diana’s first husband.

It was not long after this that she really began to come into her own as the rescuer of her other siblings. During the war she gained much kudos within the family by having the two baby Mosley boys to stay with her and Derek while their parents were in prison for pro-German activities before the war. When Nancy was dying from a particularly painful form of cancer, it was Pam who she wanted with her when the pain was at its worst, and it was also Pam – since she was so practical – who played an important part in looking after Lady Redesdale just before her death.

After her divorce from Derek she went to live in Switzerland, where it was a joke among the sisters that she knew all the Gnomes of Zurich. When she returned finally to England she settled down to a contented old age at Woodfield House in the tiny Cotswold village of Caudle Green, midway between Cheltenham and Cirencester.

It was here that I first met her as I also lived in Caudle Green, and for twelve very happy years I worked as her cleaning lady and also became her friend. When I first arrived at Woodfield House, I had no idea that Pamela Jackson was one of the Mitford sisters and when the penny dropped, I simply could not believe that this lovely, amusing and compassionate lady really was the ‘Other’ Mitford, and very few people knew it.