The Parthenon Enigma (38 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

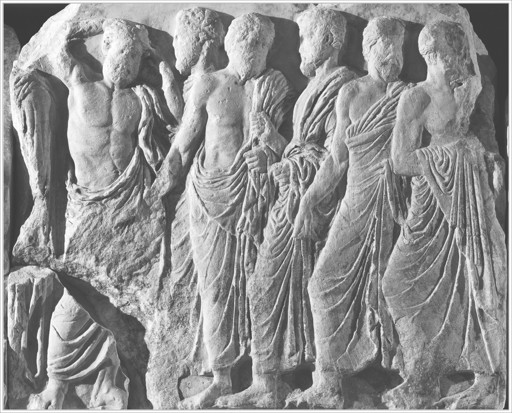

Tray bearer (N15) and men carrying water jugs, north frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.73

)

Behind the musicians march groups of older men, sixteen on the north frieze and seventeen or eighteen on the south (

this page

–

this page

, following page, and 196–97). The positions of some of their hands, held up with fingers pressed together, have led some scholars to imagine olive branches, once painted here against the background of the frieze. This would link them to the

thallophoroi

, the elders of the city who carried branches in the Panathenaic procession.

157

Xenophon tells us that “they choose the beautiful old men as

thallophoroi

for Athens.”

158

On the north frieze, one of the men is seen to stop and turns to face the viewer straight on (above). In an arresting gesture he raises both arms to adjust the wreath upon his head. Drill holes preserved in the marble show where a metal crown had been attached.

159

These groups of men represent the most senior marchers on the frieze, epitomizing the finest and most handsome of the Athenian elders.

Group of elders, with one crowning himself, north frieze, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.74

)

Finally, we come to the parade of chariots and horsemen that takes up roughly half of the north and south friezes and most of the west frieze (

this page

,

this page

–

this page

, and

this page

–

this page

). Here we must ask: If this represents the fifth-century Athenian army, why are there chariots, which had not been used in Greek warfare since the end of the

Bronze Age, some seven hundred years earlier? And where are the

hoplites? We know from Thucydides that hoplites did participate in the historical Panathenaic procession, at least by 514/513

B.C.

He tells us that when the tyrant

Hipparchos was assassinated while serving as procession marshal that year, his brother,

Hippias, rushed to the hoplites who were marching and confiscated their weapons.

160

The complete absence of the hoplite foot soldiers makes it most unlikely that we are looking at a fifth-century army. These problems go away if we understand the soldiers and chariots to represent the forces of

Erechtheus during the early days of Athens.

We will remember that

Erichthonios is said to have appeared at the first Panathenaia as a charioteer with an armed companion at his side.

161

And we have already seen an image of a charioteer carved on the marble frieze of the Old Athena Temple at the end of the sixth century (

this page

). This figure may well represent the hero Erechtheus/Erichthonios. We learn from

Nonnos, writing in the fifth century

A.D.

, that Erechtheus was intimately associated with the yoking of horses to chariots and that he brought his stallion Xanthos (“Light Bay” or “Auburn”) under the harness, teaming him together with the mare Podarkes (“Swift-Footed”).

162

Both horses were sired by Boreas, the North Wind, and born to the Sithonian Harpy,

Aellopos (“Storm-Footed”), after he raped her. Boreas gives the horses to his father-in-law, Erechtheus, as a “love price” in payment for

Oreithyia, Erechtheus’s daughter whom Boreas abducts from the banks of the Ilissos River. Thus, the chariot groups seen on the Parthenon frieze are closely associated with Erechtheus and evoke the strategic advantage they provided the Athenians in their war against Eumolpos.

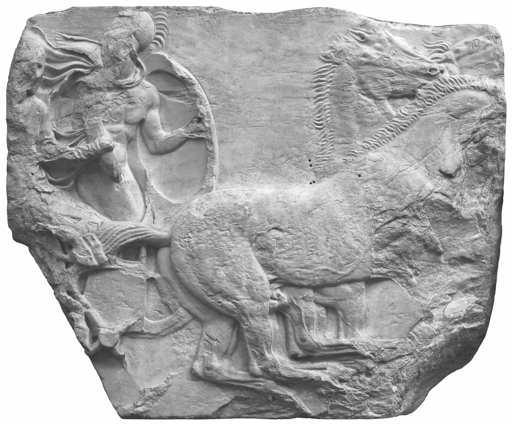

We find ten four-horse chariots on the south frieze and eleven on the north. Each has a driver and armed rider with helmet and shield (

this page

–

this page

,

this page

,

this page

,

this page

, top, and front and back of book) looking very much like the

apobatai

, the armed chariot riders who competed in a special class of Panathenaic event. This contest required the soldiers to mount and dismount a chariot moving at full speed.

163

The oldest and most distinctive event of the Panathenaia, the

apobates

race was open only to members of the Athenian tribes. Plutarch suggests this was an especially demanding event in the Panathenaic Games, duplicating the harsh conditions of combat, which required robust athleticism while carrying a full load of armor and weapons.

164

Those performing this remarkable feat on the Parthenon frieze are not Athenians taking part in the historical games but their legendary forebears who actually made war this way.

Inscriptions from the second century

B.C.

locate the

apobates

race in the vicinity of the City

Eleusinion, the temple to Demeter and Kore perched on the southwest slope of the Acropolis (just above the Agora).

165

Sometime in the fourth century

B.C.

, a victor in the

apobates

race set up a monument here in the City Eleusinion to celebrate his triumph (

this page

, bottom).

166

It features a sculptured relief showing the athlete driving a four-horse chariot, its composition and iconography matching that of the charioteers on the Parthenon frieze.

South frieze, Parthenon, showing cattle led to sacrifice (lower right), followed by musicians, elders, chariots, and horsemen. (illustration credit

ill.75

)

There is good reason to believe that the

apobates

race commemorated the first Athenian victory, the one enabled by Erechtheus’s introduction of the chariot. This would explain why the event was open only to the scions of old citizen families, the perceived descendants of the earliest Athenians. It would also explain why the race seems to have been run to the City Eleusinion as its final destination.

167

Conducting the

apobatai

toward the Eleusinion connects it with the defeated Eumolpos, who came to be so closely associated with Eleusinian cult. And there is, as well, the matter of what would otherwise be a strange detour taken by the Panathenaic procession on its way up the Acropolis; beginning at the Dipylon Gate at the northwest of the city, the sacred train went deliberately out of its way to circle the Eleusinion (insert

this page

, top).

168

To do so would make sense if the sanctuary was believed to occupy the site of Eumolpos’s encampment at the foot of the Acropolis, and thus an important place of memory around which the Athenians could take a victory lap.

169

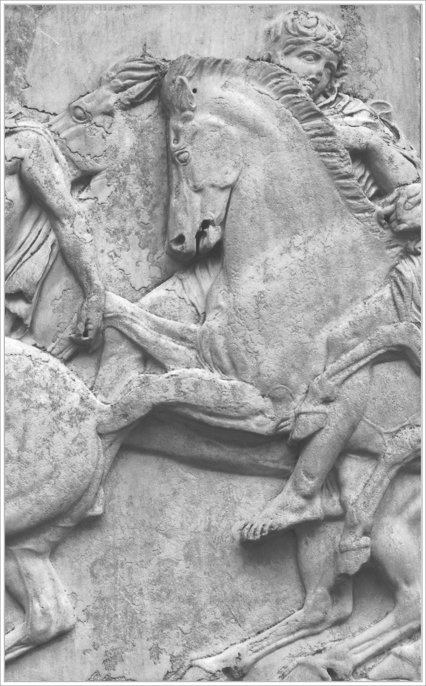

Horses and riders dominate the composition in terms of sheer numbers of figures, occupying all of the west and more than a third of the north and south sides of the frieze (

this page

,

this page

–

this page

, facing page, above,

this page

and

this page

, and front and back of book). Interpreters have undertaken the counting of horsemen, looking for all manner of encoded historical and political meanings.

John Boardman, for instance, has counted 192 horsemen in all and sees in this the number of the fallen at Marathon.

170

Several scholars distinguish four groups of fifteen horse riders on the north frieze and see in this a reference to the four pre-Kleisthenic tribes of Athens.

171

They then count ten ranks of six riders on the south frieze, as a reference to the ten tribes created by Kleisthenes in 508.

172

These various ranks of riders are differentiated through their costumes and equipment. Some wear Thracian caps, others double-belted woolen chitons, and others still the himation, or cloak. We see some riders in metal or leather body armor, some with helmets, others with flat broad-brimmed traveler’s hats, and still others wearing hats of so-called Thracian style, with three flaps. In fact, to see in the imagery a fifth-century Athenian army taking part in the Panathenaic procession may inevitably oblige one to ascribe to these mounted figures multiple levels of meaning at once.

173

Charioteer and armed rider, south frieze, slab 31, Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.76

)

Victory monument,

apobates

race, found near the City Eleusinion, Athenian Agora. (illustration credit

ill.77

)

Horse rider, north frieze, slab 41. Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.78

)

According to

Aristotle, however, it was only in days of old that the cavalry dominated the army.

174

In addition, there is no evidence for the participation of the cavalry in the Panathenaic procession. Throughout the historical period, mastery of horses was viewed as noble, harking back to the glorious past, but by the time of

Perikles it was a decidedly antiquarian pursuit, much as polo is today. Indeed,

Xenophon points to the heroic associations of the equestrian tradition, one that maintained its aristocratic cachet across the centuries.

175

It is far more plausible, then, to see the horse riders on the Parthenon frieze as members of the heroic

cavalry of Erechtheus, noble forebears of the venerable tradition of the Athenian knights, rather than as some anachronistic presence in a fifth-century spectacle.

176