The Parthenon Enigma (40 page)

Read The Parthenon Enigma Online

Authors: Joan Breton Connelly

In fact, a “

language of images” and a “language of texts” exist quite independent of each other.

189

Sometimes they overlap, but more often they take parallel tracks that never intersect. Art can inspire words just as words can inspire art. And a myth or story that is “in the air” at a particular moment can find expression equally in either. In the course of history,

myths can be retold and codified through visual as well as through textual and oral expression, not to mention through ritual itself. Just like the chorus of serving maids in Euripides’s

Ion

, who view the sculptures decorating the

temple of Apollo at Delphi, the poet might have walked around the Parthenon and been inspired by the stories that its sculptured figures tell.

190

We have no difficulty accepting that

the Parthenon sculptures inspired Keats’s poem “On Seeing the Elgin Marbles for the First Time.” Or that, two years later, in 1819, in “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” the poet would transmute his experience of the Parthenon frieze into that of viewing a more compact artifact, a fictional Greek vase:

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

…

What pipes and timbrels?…

…

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest

,

Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies

,

And all her silken flanks with garlands drest?

From these lines we can hardly divorce the figures of the Parthenon frieze seen by Keats in the

British Museum: maidens, pipe players, offering bearers, sacrificial victims, priest, and lowing heifers.

The technique used by

Euripides has been called cinematic, employing “zoom” and “wide-shot” narration to modulate the audience’s intimacy with powerful visual icons.

191

In the

Erechtheus

, he gives us a close-up of Pheidias’s statue of Athena Parthenos wrought in gold and ivory: “Raise a cry [

ululate

], women, so the goddess may come to the city’s aid, wearing her golden

Gorgon.”

192

The chryselephantine statue of Athena did, indeed, wear a Gorgon-headed aegis upon her chest (insert

this page

, bottom) and Euripides effectively “zooms” in on this detail, focusing his audience’s attention on the famous cult image. I would argue that Euripides also accesses the sculptures of the Parthenon’s west pediment when he places on the lips of

Praxithea these words: “Nor will

Eumolpos and his Thracian army ever—in place of the olive tree and golden Gorgon head—plant the trident on this city’s foundations and crown it with garlands.”

193

So, too, he evokes the

aulos and

kithara players that we see on the north frieze (

this page

,

this page

, and front of book) when he has his chorus of old men sing: “taking up the task of my aged hand, the Libyan (lotus) pipe sounding to the kithara’s cries.”

194

The next slab over from the

musicians on the north frieze, in fact, shows a group of old men, one fixing a wreath upon his head (

this page

). It can be no coincidence that Euripides’s chorus intones: “

and may I dwell peacefully with grey old age, singing my songs, my grey head crowned with garlands.”

195

Thus

Euripides seems to draw poetic inspiration from the Parthenon itself. He is even more imaginative when he focuses on the groups of men and maidens depicted on the east frieze (

this page

,

this page

, and front of book). In his mind’s eye, the marble maidens come to life as the chorus of old men asks: “shall the young girl share with aged man in the dance?”

196

It may have been a bit of fantasizing on the part of the poet by now approaching sixty. For these are the

parthenoi

of the first Athenian maiden chorus, and their dance partners will be the young ephebes,

not

the old men of the city.

THE PARTHENON HAS

long been recognized as the most lavishly decorated of all Greek temples. The profusion of sculptures adorning its pediments, metopes, and frieze, its chryselephantine statue of Athena Parthenos, no less than the sophistication of its architecture, set it apart from other temple buildings. Indeed, its abundance of adornment has aptly been described as “hyper-decoration.”

197

This distinctly Athenian predilection for opulence has, in turn, been read as a wasteful effort to flaunt and enhance Athenian ethnic prestige and political power.

198

But one can imagine a further motivation for the hyper-decoration of the Parthenon, one beyond pretension. The vivid and abundant sculptural adornment might have served much the same purpose as the astonishing cultivation of the literary and rhetorical arts at Athens during this same period. In her study of

Plato’s view of the uses of philosophy,

Danielle Allen articulates Plato’s theory of the role of language in politics. The philosopher calls for the vivid (

enarges

) and abundant use of language to educate the citizenry toward the formation of values.

199

We might make the same claim for architectural sculpture.

Sculptured images permanently visible on major monuments went a long way in teaching and sustaining these values for the citizens that beheld them every day. And they spoke with equal eloquence not just to the elites, who could read, but to those of the populace who were illiterate. The primary

function of the hyper-decoration of the Parthenon, in some sense of the Parthenon

tout court

, was paideia, the education of the young by means of a visual extravaganza.

As Allen has shown, Plato and

Lykourgos recognized the central role of myth, poetry, and aitiology in teaching the young. Architectural sculpture provided a giant screen onto which the myths could be projected. Turning the next generation toward virtue by reminding them of the sacrifices made and the oaths taken by the youths and maidens of early Athens inspired generation after generation of young Athenians to do the same. The forefronting of Athenian youths in the Panathenaic competitions, especially in the tribal contests, the choral dances of the night vigil, the procession, and on the Parthenon frieze itself makes explicit the necessity of engaging the next generation in just what it means to be an Athenian.

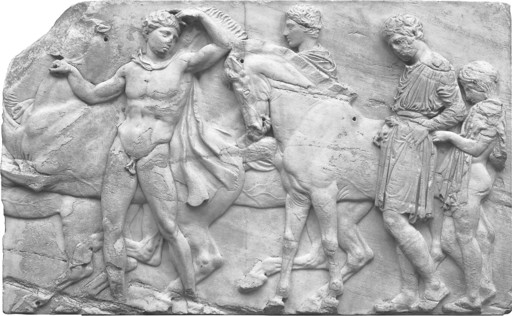

Nude male, horse rider, adolescent, and boy, north frieze, slab 47. Parthenon. (illustration credit

ill.82

)

The carved figures render the gods and the ancestors eternally present. They teach the

genealogy of a venerable people, the origins of their enduring rituals, and the values that defined Athenian identity. Now, at last, we can see a powerful myth narrative animating the lifelike features of the Parthenon frieze to help us recognize a more profound meaning in its imagery. By engaging with a new paradigm and adjusting our perspective by a few degrees, we can see things that have not been evident for centuries.

At the very

northwest corner of the Parthenon frieze is an arresting figure, among the first that visitors might see as they emerge from the

Propylaia and make their way toward the front of the temple. Should

they stop here and make the effort to look up into the shadows of the colonnade, they would behold a beautiful male nude who steadies a rearing horse while gesturing with his left hand to three young men who follow behind him (facing page). It is as if he were urging them forward. The first is a young mounted rider shown in profile, the next is an adolescent on foot, wearing a short tunic, and the third is a boy much younger by far, partially nude with mantle thrown loosely across his shoulders. We seem to be looking at the ages of man: boy, youth, and young adult are hailed and welcomed into the march of life as Athenians.

Farther down this north frieze, we see the group of old men marching. There is the one who stops in his tracks and deliberately turns toward the viewer, lifting his arms to crown himself (

this page

), his strong, mature body caught in an arresting pose. He represents the best, the noblest, and the most handsome of Athenian elders, the very pinnacle of what a man can become when nurtured by and devoted to his city. The frieze thus provides a mirror in marble, reflecting back the ideal citizen from childhood to maturity, his glory, not his individuality, not the poetry or philosophy he makes, but in the fact of his being one of the many. It is the responsibility of Athens to educate him in the history, identity, values, and interests into which he has been born. In doing so, the polis provides the answer to that most compelling of all human questions: Where do I come from?

6

WHY THE PARTHENON

War, Death, and Remembrance in the Shaping of Sacred Space

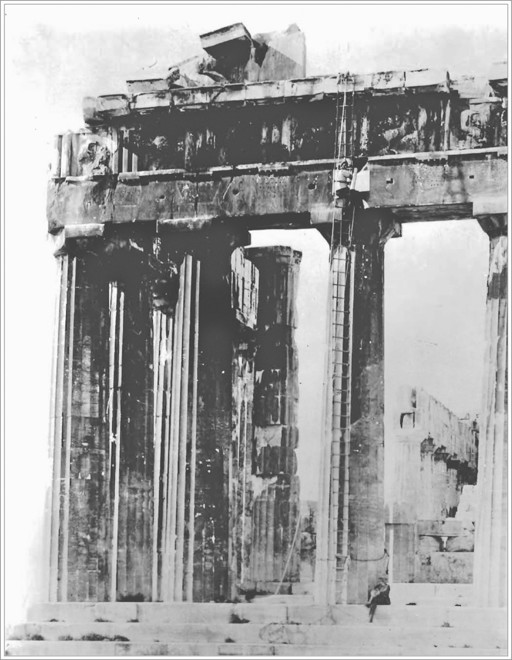

THE GERMAN ARCHAEOLOGIST PITCHED

out a challenge.

Eugene Plumb Andrews was intrigued. Freshly graduated from Cornell, Andrews had come to Greece on a fellowship from the American School of Classical Studies with hopes of running in the first modern

Olympic Games the following summer. On this blustery afternoon in December 1895, atop the Acropolis summit, he was one among many students who had gathered to hear what Dr.

Wilhelm Dörpfeld had to say. Young Andrews would come away seized by a new and overpowering purpose, one that would cause him to set aside his Olympic dreams altogether.

Directing attention to the architrave, the great hundred-foot lintel resting atop the eight columns of the Parthenon’s east façade, Dörpfeld had pointed out deep holes just below the

metopes. He then drew the students’ attention to the outlines of great circles, each 1.2 meters (4 feet) in diameter and barely visible as a discoloration in the marble. These were the “ghosts” of metal shields that once hung here, booty seized from a defeated enemy and displayed as trophies. But whose victory?

Dörpfeld then pointed to hundreds of small holes drilled just beneath the triglyphs. These comprised twelve groups of cuttings, each of three lines, except for the last two groups of two lines each. The professor

explained that these were dowel holes for the attachment of large gilded bronze letters that once spelled out a dedication. By studying the relative positions of the holes, one could, in theory, make out the letters of the alphabet that had been attached and in this way work out the inscription. “Such things have been done, and it is time that this were done,” Dörpfeld mused on the puzzle he was presenting.

1

Eugene Andrews decided on the spot that

he

was the man to solve it.

Within a month, Andrews was riding up the Parthenon’s east façade each morning in the rigging of a boatswain’s chair (below), grateful no doubt for his experience as a yachtsman. He took strips of wet paper,

crossed at right angles, and pushed them deep into the drillings; thus Andrews took squeezes of each cluster of holes in the inscription. The work was arduous. He could complete just one squeeze a day, leaving the paper to dry overnight and praying that winds would not blow it off before morning.

2