The Pines (4 page)

Authors: Robert Dunbar

No. She tightened her grip on the steering wheel. The sands were not truly barren. They produced the stunted, twisted pines…as her body had produced her son.

Furious with herself for the thought, she jerked the wheel, and a dwarf pine rasped against the car. Cursing, she concentrated on driving. There w ere so many things to avoid.

She switched on the radio—a garbled voice. She twisted the dial but could find nothing clear, the distant signals a cacophony of chopped and liquid sound. She turned it off, and the car crept along. Nailed to a tree, a weathered plank indicated the fork to Munro’s Furnace.

The road narrowed until it became a sandy rut walled by brush, and now pine boughs crushed against both sides of the car. Around a turn, the brush thinned, and another winding branch diverted from the main trunk of the road. Dark shells of ruined houses passed.

Soon, her own home loomed, dark and ugly in the windshield. It was her late husband’s house really, the house he’d been born in, last surviving structure of an old mill town. The present-day town of Munro’s Furnace, such as remained, lay another three-quarters of a mile down the road.

As the car crunched to a halt on gravel, she stared unblinking. No matter how long she lived here, it always proved something of a shock, this reality. Funny, but in her mind she always pictured the place the way it had been when they’d first begun fixing it up—scaffolding and ladders, cans of paint and bags of cement everywhere. A royal mess, but she hadn’t cared because they’d been happy, working together until…

Glaring headlights held the cobbled-together structure in cruel scrutiny: clapboard walls beneath phantom paint; boarded first-floor windows she couldn’t afford to repair; collapsing front porch propped up with old bed slats and cinder blocks. She switched off the engine, got out, and night fell on her.

Her grandmother’s home in Queens—no matter how miserable she’d been there as a child—had at least held life. This house lay black and silent. Looking up, she strained to make out the blind diamond panes of her son’s bedroom window.

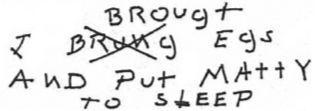

He’s been

asleep for hours.

She allowed her gaze to drift across the hanging eaves, along the tilting gabled roof…missing shingles…crumbling chimneys.

While she limped around to the back, shoulders straight, she forced herself to walk closer to the bristling shadows, farther from the house than necessary. She mounted the wobbling steps to the porch and stood, fumbling her key into the kitchen door. Why couldn’t Pamela ever remember to switch on the porch light before she left? Something wet and warm pressed against the back of her hand, and she jumped. “Stupid dog!”

From the darkness of the porch came a yawning whine and the scratching of claws on wood. “Get away, Dooley.” When she got the door open, the moldy smell of the house met her like an invisible wall. “Go back to sleep. You can’t come in.” She heard the dog yawn again and flop back down on the porch with a deflating sigh.

Pulling the door closed behind her, she could see nothing, and she stumbled across the rough wooden floor, feeling along the wall for the switch. She flinched when yellowish light flooded the kitchen.

A three-inch millipede tapped along the stove, waving its antennae in blinded confusion. Darkness bulged at the door. Pamela’s note lay on the crumb-littered tablecloth.

Granny Lee once had a dog put to sleep.

Her thoughts grew fuzzy and, yawning, she crumpled the note. The cellar door stood slightly ajar. She closed it, turned the old key, remembering how they’d used to tease her about being afraid of the basement at her grandmother’s house, and how Aunt Jeanie had always been inventing errands to take her down there.

Such a night for

reminiscences.

The house returned to absolute darkness as she switched off the kitchen light, and a cricket began to throb beneath a floorboard. Groping her way into the living room, she walked into a chair and cursed, then felt her way toward the stairs. The other rooms on the first floor had been closed off. From outside, the voices of the night—the insects and the whispering trees—sounded low and indistinct.

As she started up the stairs, her hand rode along the smooth banister, smearing the dust. She turned left at the landing. Boards creaked under her footsteps along the hall—a loud thump followed by the weaker, softer sound. She went straight to her room.

Without turning on a light, she put the scanner on the dresser, then pulled bobby pins and elastic bands out of her hair. A hair band knotted, and she yanked it out, tossed it on the dresser. Feeling sweaty and dirty, but too tired to do anything about it, she fell across the too-soft, untidy bed. Mounds of laundry lay heaped around her, and her leg ached.

From the scanner, police calls muttered distantly. She listened to them drone and thought about getting undressed, knowing her reflexes would alert her if the tone that preceded ambulance calls sounded. The scanner’s small red light was somehow comforting, and her mind drifted to the night-light Granny Lee had given her so long ago. Even as a child, she’d thought it cowardly and every night had dragged herself out of bed to unplug it, loathing herself all the while.

Something rattled overhead. It could have been another tile that had worked loose, clattering across the roof…or it might have come from the attic. She listened to the house, to the beams that groaned like an old wooden ship.

She seldom truly slept anymore. Habitually, she’d push herself to exhaustion, then lie twitching on the edge of wakefulness, only to be active at dawn. The hours stretched long before her. Lying in the dark, eyes open, she always ran out of the distractions and evasions.

In the woods.

Whenever she was motionless, questions seemed to whirl around her. She’d expected so much from herself, but what had she done with her life? She was thirty-two years old now and trapped in the pines—ten years almost. It seemed so much longer than that…and so much shorter. All the things she’d wanted…

Too late.

But her work on the ambulance was important. She tried to hold to that thought as the redness of the scanner grew hazy. Her scalp still smarted from the hair band, and her thoughts drifted to how Aunt Jeanie, jealous of her light skin, had always teased her about her kinky hair, and how Granny Lee had always tried to straighten it with chemicals that stank and burned.

No…I don’t

want…

Her hair would come out in fistfuls, and always there would be scabs on her scalp for weeks afterward.

No.

She closed her eyes, and the darkness was complete.

The bedroom window was open but with the shade drawn against the night. Ten yards from the house, beyond the waving grasses, pines swayed, making a noise like the sea, like a still-boiling primeval element.

And the dream began.

Always, it was the same: torturous fragments raced through her mind, baffling glimpses of frenzy, the savage joy of forest revels, the crazed pursuit of those that fled, blood gushing hot, the rending of fawn’s flesh and the splattering of trees in infantile desecration, mad decoration, alone and not alone. She writhed on the bed.

A different noise filtered into her nightmare—a rhythmic groaning, full of the creak of bedsprings.

Half awake, she got up and made her way along the hall. At its end, steep narrow stairs were set in a closet like alcove, and she went up them practically on all fours, feeling her way in the dark.

The attic room had a sour, baby smell. She felt in the air for the string, and the naked, insect-encrusted bulb blazed, dancing. The attic was a mad jumble of chairs, boxes, broken and unwanted objects from all over the house.

Oh Christ…I have to

clear out this mess.

Maybe tomorrow she would get to it.

The cot shook, creaking with the boy’s efforts. Naked and sweaty, his ten-year-old body twisted into serpentine knots on the bedding, and his teeth locked in the rumpled pillow he ripped with convulsive jerks of his head. The boy was asleep.

She stared. His hair was curly like hers, coppery like his father’s, and in the leprous bulb light, his damp skin had an unwholesome yellow sheen. He was the source of the sour smell. She wanted to turn away, obliquely wondering what wordless images comprised his dreams.

He needs a bath.

His sleep-swollen face remained buried in the pillow.

He growled.

“Matthew.”

She simply spoke his name, and though his body remained tensed, all movement ceased.

Her son. For perhaps the thousandth time, she wondered about herself, about why she felt no tenderness when she gazed on this child. She would not pretend to herself. Her mind slid to her late husband: she’d let Wallace down in so many ways. The house. The boy.

And the awful thing is I don’t really feel sorry, can’t even feel guilt anymore. Can’t feel anything.

Like hot water scalding dead flesh, her thoughts brought only an echo of pain.

I’m paralyzed.

There were long scratches on the boy’s legs.

He’d been in the woods again, she thought uneasily.

In spite of everything I’ve said to Pamela, he’s been out in the woods.

She stared another moment. The sheet was a graying tangle, tucked between his legs, and she thought he might have wet the bed again.

If I try to change the bedding now, I’ll only wake him.

She switched off the light.

Pamela can do it in the morning.

As on so many other nights, she groped her way back down into the narrow darkness.

The sky between dissolving stars grew colorless.

Thick and brown with tannic acid, the sluggish waters of the creek flowed noiselessly over their sandy bed. The fish—the stunted sunfish and carp of the barrens—began to drift up from their murky holes to feed on insects caught on the surface. Occasionally, a young perch would clear the water, landing with a splash, explosive in the prevailing hush. Then broadly circling ripples would spread across the width of the stream, lap softly against the crumbling banks, and vanish.

At the water’s edge, a large shape grew gradually more distinct—a man on the bank. Unmoving, he’d stood thus for some time, staring at something lodged upon the rocks.

The dawn light began to glint off tangled yellow hair that stuck out beneath his soiled hunting cap. Al Spencer was a big man, six and a half feet tall. Grizzled face too large, watery eyes too far apart. His whiskey belly bulged under a plaid jacket. Shoulders hunched, he studied the thing in the water; then he peered back into the still-dark pines. Good. Wes was nowhere in sight.

The stream threw off a grayish light that sloshed across the bank. He took off his jacket, folded it and laid it carefully on the sand; then he kicked off his shoes and slipped off his suspenders. The rest of his clothes made a neat pile.

Naked except for his cap, he waded into the stream, slipping on rocks slimy with green moss. The corpse was rigid, shifting almost imperceptibly in the vague current. Al grabbed it by one arm and yanked it around.

The boy’s face had become a bloated abomination. Dark hair floated, soft as seaweed, spreading around the head, and gelid eyes had swelled from their sockets, yet clung, opaque as jelly-fish. A huge tongue engulfed blue lips. Even the neck had expanded, become a puffy, waterlogged trunk slashed with purple wounds that leaked thin fluid. The green T-shirt, too tight now, rode up and exposed the round white stomach.

There was a watch on the left wrist.

Al crouched low in the shallows, the water warmish on his genitals, and with furtive gentleness, pried the watchband off the swollen wrist, over the stiffened fingers. Barely glancing at it, he slipped it onto his own wrist. Then he stuck his hands in the dead boy’s pockets but found nothing. He giggled—other things had swollen too. With a quick heave, he flipped the body over onto his stomach and fished out the wallet.

It contained twelve dollars, some pulped identification, and a graduation photo of a girl. He squeezed the money in his palm and tossed the wallet into the creek. It floated for a second before it opened and spun downward.