The Pope and Mussolini (43 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

“He has taken off his coat, and in his sports shirt he appears astonishingly young. Heeding nothing but his instinct, he leaps at me. Before I have time to utter so much as an exclamation, I am caught up in strong arms.”

33

The French scandal led to a raft of foreign news reports about the Duce’s voracious sexual appetite. The reports, said Mussolini, were greatly exaggerated. “If I had had to couple with all those women that they claim I have,” he told an interviewer, “I would frankly have had to have been not a man, but a stallion.” Two years later, as he bantered with a woman acquaintance, he quipped that his flesh did not allow him to be a saint. While few things tempted him—he ate mostly fruit and vegetables and had no interest in money—he had one weakness, he acknowledged, that would always stand in the way of any saintly aspirations.

“You aren’t the only one in the world,” she pointed out. “I’ve always wondered what use having been virtuous is when one is old.”

“In Romagna,” replied Mussolini, “we have a proverb.… In youth, give your flesh to the devil, in old age, give your bones to the Lord.”

34

Being a ladies’ man had always played a part in the Mussolini cult, and the Fontanges affair did nothing to change this. In early September, as a band played at a festival on a Sicilian beach, Mussolini danced with the local women, some young, some old, some thin, some fat, some attractive, others not. “Dancing is a religion in Romagna,” he said. “It takes the place of Catholicism.”

As Mussolini swayed to the music, his secretary rushed onto the dance floor clutching a telegram. An Italian submarine, off the Sicilian coast, had just torpedoed a Russian cargo ship bringing provisions to Republican Spain. The attack was part of a recently imposed blockade that risked triggering a larger European war. After pausing a moment to read the message, the Duce chose another partner. When the song ended, he asked, “Are there other telegrams? If every turn around the floor they announce another torpedoing, I’ll never stop dancing.”

35

C

HAPTER

TWENTY

VIVA IL DUCE!

I

N AUGUST 1937 NEWSPAPERS BEGAN REPORTING MUSSOLINI

’

S PLAN

to visit Germany.

1

It would be a fateful trip. For five days, in late September, Hitler stood at the Duce’s side, carefully choreographing a series of processions, marches, and inspections to impress Mussolini with the power of the Nazi regime and the Germans’ devotion to their Führer. The culmination came in Berlin on September 28 when eight hundred thousand people filled a field near the new Olympic stadium. Along the route leading there, nearly three million Germans cheered the dictators, having been brought in by bus and train from throughout the Reich. When the two leaders emerged onto the field the crowd roared. Hitler spared no praise, hailing Mussolini as “one of those rare solitary geniuses who are not created by history but who make history themselves.” Hitler later called him “the leading statesman in the world, to whom none may even remotely compare himself.”

2

Mussolini had carefully prepared his text in German and, after Hitler’s effusive introduction, rose to speak. When Fascist Italy had a friend, he proclaimed, it marched alongside him “right to the end.” But a sudden downpour spoiled the desired effect, as the master of bombast

struggled to make out the blurry words on his rain-soaked sheets. The crowd had no idea what he was saying.

3

“Compared to Hitler’s demonstrations,” observed an Italian witness to the event, “those of the Italian Fascist seem like just a bunch of people running around shouting. In his speeches, Mussolini rambles, expressing commonplaces in dramatic fashion and self-evident truths with great solemnity. He addresses the ignorant masses, and speaks for them, gesticulating with his face, his body, his eyes, with the moves of a charlatan. Hitler is always composed. When Mussolini appears … hands on his hips, he seems like a circus ring master. Hitler by contrast seems like an apostle, a political, religious leader.”

4

Mussolini and Hitler in Munich, September 1937

The Duce was deeply impressed. “What I saw here,” he told his wife, Rachele, by telephone as he prepared to leave, “is unimaginable.”

5

Although he had promised he would convey the pope’s complaints, Mussolini never did mention them to Hitler.

6

Amid the huge adulatory crowds and the imposing displays of military strength, he could not bring himself to raise such an unpleasant subject.

7

Mussolini vowed to host Hitler for a visit in the Eternal City that would outshine his own reception in Germany. Cardinal Baudrillart, writing in his diary, wondered whether the weakened Pius XI could survive such a painful sight.

8

For the Vatican, it was becoming increasingly important to differentiate between the two totalitarian states. Immediately following Mussolini’s visit to Germany,

La Civiltà cattolica

published a piece making just this distinction. People who equated Nazi Germany with Fascist Italy, the journal argued, “do a great injustice to the Fascist Regime.” Hitler was seeking to unify the German people under a new, pagan religion, its slogan the divinity of the blood and the soil. Mussolini was doing the opposite, unifying Italians under the Catholic religion. The two could scarcely be more different.

9

On Mussolini’s return from Germany the pope, although upset that the Duce had not raised the issue of the Church with Hitler, again asked his help with the Führer. It was in Mussolini’s own interest, he argued, to get Hitler to stop persecuting the Church. Given Italy’s links to the Third Reich, the Nazis’ anti-Church campaign was harming Italian Fascism’s good name.

10

In another sign of his embrace of Nazi Germany, Mussolini announced in December that Italy was withdrawing from the League of Nations. Hitler had removed Germany from the League shortly after coming to power in 1933. The pope looked on with increasing unease. He was also embarrassed that so many non-Italian cardinals thought him naïve in expecting Mussolini to be a moderating influence on Hitler.

11

“It is not the Duce who exercises any influence on the Führer,” remarked the French Cardinal Eugène Tisserant, “but rather the Führer who exercises it over the Duce.”

12

In the pope’s Christmas speech to the cardinals, he again lamented the persecution of the Church in Germany.

13

It was a message he was sharing with all who would listen.

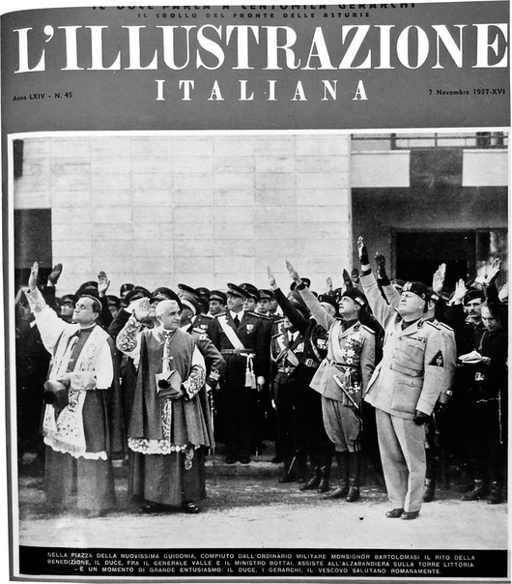

Mussolini dedicates the new town of Guidonia, as the local bishop joins in the Fascist salute, November 1937

Convinced he had little time to live, Pius XI believed God was keeping him alive for a reason. “His fragile state of health,” observed the French ambassador, “is unfortunately weakening, not his intellectual capacities, but his physical strength.” Cardinal Jean Verdier, archbishop

of Paris, saw the pope twice around Christmas. At their first meeting, the cardinal was delighted to find him lively and attentive, but the next time the pontiff was feeble, barely able to speak, and unable to read the papers he had in front of him. Sometimes the pope was alert and articulate. Other times he was frail and frustrated. Yet, during his sleepless nights, he felt God’s presence, imparting a divine message it was his duty to pass on before he died.

14

Cardinal Baudrillart noted the change in his diary. “The pope remains very lucid, but his willpower is becoming more hesitant.” Nor did the French cardinal think the secretary of state offered an adequate substitute. “Despite all of his eminent qualities,” he observed, “Cardinal Pacelli does not seem to have a very firm mind, nor a very strong will.”

15

Later in the month, Baudrillart observed, telegraphically: “Now atmosphere of the end of regime: secret intrigues.”

Mussolini was irritated. Whipping up Italian enthusiasm for Germany was a challenge, even with his massive propaganda machine. Only two decades earlier, the Italians had fought a war against the Germans,

and all the Nazi talk of the superiority of the Nordic race was not making his task any easier. The last thing Mussolini needed was for the pope to convince Italians that Hitler was an enemy of the Church.

Mussolini, from Palazzo Venezia, announces Italy’s withdrawal from the League of Nations, December 1937

It was time, thought Mussolini, to apply some pressure. He delivered his message through Guido Buffarini. Elected mayor of Pisa in 1923 at age twenty-eight, Buffarini became Mussolini’s undersecretary for internal affairs ten years later. Ruddy complexioned, sad-eyed, and fat, intelligent and shrewd, devoid of any moral principles, Buffarini was a blowhard with a talent for intimidation and a penchant for feathering his own nest.

16

On December 30, Buffarini summoned the papal nuncio. He had evidence, he said, that Catholic Action groups were again mixing in politics. If this continued, he warned, a violent popular reaction was sure to follow. The dumbstruck nuncio denied the charge, but to no avail.

17