The Pope and Mussolini (47 page)

Read The Pope and Mussolini Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

Tags: #Religion, #Christianity, #History, #Europe, #Western, #Italy

The journal offered its enthusiastic support to Belloc’s proposal to have governments segregate the Jews from the larger Christian population.

5

Jews, it charged, controlled both high finance and Communism, in Jewry’s “double game” of fomenting revolution to “extend its dominion over the world.” Because Jews by their nature sought to rule the world, they could never be loyal to the country in which they lived. This was why they were the most enthusiastic supporters of both Freemasonry and the League of Nations. In short, the Vatican-vetted text reported, Jews sought to reduce Christians to their slaves.

6

In the months leading up to Mussolini’s assault on Italy’s Jews, which would be kicked off in July,

La Civiltà cattolica

helped prepare the way by warning of the Jewish threat and the need to act against it. The journal heralded the importance of a spate of recently published anti-Semitic books. In February 1938 a review of Gino Sottochiesa’s

Under Israel’s Mask

corrected the author—described as a man of “secure Catholic faith”—for his mistaken impression that

La Civiltà cattolica

called only for “charity and conversions” in dealing with the Jewish threat; it had long urged governments to adopt protective measures against Jewry.

7

Nor was

La Civiltà cattolica

alone. In the months before the anti-Semitic campaign began, much of the Italian Catholic press was urging the government to take action. Especially influential was

L’Amico del clero

(The Clergy’s Friend), the official publication of the Italian national

association of Roman Catholic clergy, which counted twenty thousand priests as members.

A spring 1938 article by Monsignor Nazareno Orlandi titled “The Jewish Invasion in Italy Too” began with the usual disclaimer: “We are not, nor can we as Christians be, anti-Semitic.” The monsignor went on to explain that while the “racist” anti-Semitism of the Nazis, based on a belief in the purity of blood, had to be rejected, “defensive anti-Semitism” was not only legitimate but necessary in the battle against “the Jewish invasion in politics, the economy, journalism, cinema, morals, and in all public life.” While thanks to the government’s vigilance, things were not as bad in Italy as elsewhere, “it is certain that many of the positions of command among us are also in the hands of the Jews who would, given the opportunity, probably do to us what they have succeeded so well in doing in other nations.” While our records are limited as to what millions of Italians who attended Sunday mass in those months heard from the pulpit, and studies are almost nonexistent, it would be surprising if they did not hear repackaged versions of these dire warnings.

8

In mid-July, while LaFarge and his colleagues were secretly drafting their encyclical in Paris,

La Civiltà cattolica

published a long, enthusiastic article on the recently introduced anti-Semitic legislation in Hungary. “In Hungary,” the journal explained, “the Jews have no single organization engaged in any systematic common action. The instinctive and irrepressible solidarity of their nation is enough to have them make common cause in putting into action their messianic craving for world domination.” Hungarian Catholics’ anti-Semitism was not of the “vulgar, fanatic” kind, much less “racist,” but “a movement of defense of national traditions and of true freedom and independence of the Hungarian people.”

9

ON JULY 14 MUSSOLINI

kicked off the Fascist campaign against Italy’s Jews with a statement on race, published in

Giornale d’Italia

, one of

Italy’s leading newspapers. The Manifesto of Racial Scientists, prepared at Mussolini’s direction, was a set of propositions drafted by an unknown twenty-five-year-old anthropologist, Guido Landra, and signed by a mix of prominent and obscure Italian academics.

10

It set out the Fascist regime’s new racial theory. Italy’s population, it stated, was “of Aryan origin and its civilization is Aryan,” and indeed “a pure Italian race exists.” Ominously, it announced that the time had come for Italians to “proclaim themselves to be frankly racist. All of the work that the regime has done thus far is, in essence, racism.” Explaining that “the question of racism in Italy ought to be treated from a purely biological point of view,” it incoherently added, “This does not mean however introducing into Italy theories of German racism.”

11

Historians have debated why Mussolini chose to mount a campaign against Italy’s Jews. For years the Jewish Margherita Sarfatti had been both his lover and his trusted adviser.

12

Several of Mussolini’s family doctors were Jewish, and after announcing the “racial” campaign, he would also have to find a new dentist.

13

Nor had he previously taken seriously Nazi claims of racial superiority. In his 1932 interview with the Jewish Emil Ludwig, he had famously said, “Nothing will ever make me believe that biologically pure races can be shown to exist today.”

14

For many historians, the timing of Mussolini’s campaign—its kickoff coming just two months after Hitler’s visit to Rome—was no coincidence. Hitler, they argue, told Mussolini during his visit that if he truly wanted to cement their alliance, he would have to eliminate the most obvious difference between the two regimes and declare war on the Jews. Dino Grandi, then Italian ambassador to Great Britain, gave this account. In this reconstruction, Hitler tried to induce Mussolini to join his battle against the Catholic Church as well. The Duce refused but agreed to join the Nazis’ anti-Semitic campaign.

15

There are reasons to doubt Grandi’s account, not least the fact that it was written after the war, when Grandi—who had never supported the Nazi alliance—was eager to blame all that was wrong with Fascism on the Nazis. But this does not mean the timing of Mussolini’s anti-Semitic

campaign was unrelated to Hitler’s visit. He was eager to impress the Nazi leadership and undoubtedly thought nothing would please it more than taking aim at Italy’s Jews.

16

La Civiltà cattolica

, which published the manifesto at the end of July, greeted with relief its statement that Italy’s racism should be “essentially Italian.” The journal worried, however, that its propositions were not clear enough. Some might interpret them as supporting the worship of blood, a Nazi concept that ran counter to Catholic teachings on the universality of humankind. The journal made no comment on the manifesto’s proposition that “Jews do not belong to the Italian race.”

17

L’Osservatore romano

, in reporting the news, quoted this sentence but offered not a word of criticism. Meanwhile many papers republished part or all of a July 17 article by a member of the

Civiltà cattolica

collective commenting favorably on the manifesto.

18

Italy’s major Catholic daily,

L’Avvenire d’Italia

, was one of them; four days later its editor, Raimondo Manzini, expressed his support for an “Italian racism” in its pages. Manzini would later serve for eighteen years as the editor of

L’Osservatore romano.

19

At 7:15

P.M.

on July 14, only hours after publication of the manifesto, the Rome correspondent for the Nazi Party newspaper,

Völkischer Beobachter

, relayed the exciting news to Germany. “Following the statement on the problem of racism, National Socialism and Fascism show that in this area too they are united. From today on,” the German journalist gushed, “140 million men profess the same

Weltanschauung

[worldview].”

20

The following day German newspapers reported the news glowingly, expressing the belief that Italy would soon announce its own anti-Semitic legislation, following the Nazi example.

21

After considerable work behind the scenes, the anti-Semitic campaign got off to a strong start. Mussolini followed it closely, assigning the task to the ministry of popular culture, which had responsibility for the regime’s propaganda. Professors of known Fascist sympathies were solicited to add their names as supporters of the campaign, libraries devoted to racist literature were organized, and an archive of twenty thousand racist photographs was planned. A group of Fascist academics

was enlisted to write about the reality of races, aimed at a broad audience. Of special importance was the launching of a new illustrated popular magazine promulgating the racial theories, to be called

La Difesa della razza

(The Defense of the Race).

22

In taking action against the supposedly dangerous Jewish threat, Mussolini was finally heeding the warnings that the pope’s emissaries, especially Father Tacchi Venturi, had been giving him. But the pope himself showed no sign of concern about any Jewish threat in Italy. What was most exercising him was the threat posed by the Nazis.

The Duce had reason to worry that the pope would oppose his embrace of German racism. But he also had reason to believe he could keep the pope from speaking out against it. If he stood firm and distinguished his brand of racism from the Nazis’, he thought, the pope would ultimately back off. The effort to differentiate Fascist racism from Nazi racism helps explain the verbal gymnastics in the racial manifesto. The distinction was also important to Mussolini because nothing angered him more than being accused of imitating Hitler.

Mussolini also knew that while the pope opposed German racial ideology, his views on state policy aimed at limiting Jews’ rights were much less clear. Indeed, the Duce was counting on using the Church’s own warnings about the Jewish threat to generate popular support for his anti-Semitic campaign.

Most of all, Mussolini knew how much the pope depended on him for favors that benefited the Church. Some of them, including trying to influence Hitler on the Church’s behalf, involved major matters. Others, such as relying on the regime to prevent publication of books Pius XI found offensive, were more minor but nonetheless important to him. One such instance was certainly fresh in the pope’s mind at the time.

In late May, Pius had learned that a new biography of Cesare Borgia was about to go on sale at newsstands in inexpensive, illustrated installments. Borgia was not a topic the Vatican was eager to have explored. Born in 1475, he was made a cardinal at age eighteen. Borgia’s father was Pope Alexander VI. Renouncing his cardinal’s hat in his early

twenties, Borgia went on to become a military leader, fathering two children by his wife and many more with other women.

23

The pope got word to Ciano that he wanted all copies of the biography destroyed.

24

Mussolini’s son-in-law ordered a halt to the newsstand publication. The government would permit the biography to be published only as a single, weighty volume, which would cut down dramatically on its readership.

25

But the Vatican soon learned that, despite Ciano’s order, the popular installments were still on sale. On instructions from the pope, the nuncio Borgongini met with Ciano on June 13.

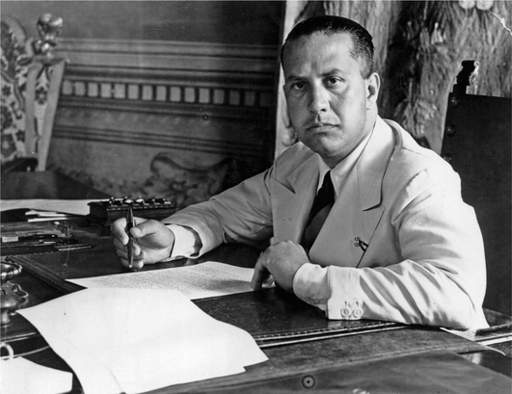

Galeazzo Ciano

Indignant that his order had not been followed, Ciano picked up the phone and called the second-in-command of the popular culture ministry, the minister being out of town.

“Rizzoli [Angelo Rizzoli, the publisher],” Ciano told him, “is the most anti-Italian, anti-fascist, anti-Catholic person imaginable.” The book, he charged, was “a lurid speculation, prepared by the Jews.” Borgongini had pointed out to Ciano earlier that the author of the biography,

Gustav Sacerdote, was Jewish. Rizzoli had to be taught a lesson. “Put your knee on his throat,” instructed Ciano, “and slap him around so that he never forgets it.”

26

A week after that meeting Ciano let the nuncio know that not only had the popular installments of the Cesare Borgia biography been banned, but so had the book itself. The following week Cardinal Pacelli wrote a note of thanks.

27

UNDER ACHILLE STARACE

’

S HEAVY HAND

, Mussolini’s campaign to demonstrate the regime’s virility was in full swing. From June 30 through July 2, the dictator presided over highly publicized athletic events aimed at showing the intrepid spirit and toughness of the Fascist Party leadership. Summoned to Rome, the provincial party heads took part in a series of “tests.” These ranged from the ridiculous (as Fascism’s portly potentates attempted to vault over fake wooden horses) to the dangerous (as they leaped over upright rows of bayonets). The American ambassador described the bizarre event, noting that as Mussolini looked on, “two competitors fail[ed] to clear the bayonet hedge with somewhat uncomfortable results.” Italian newspapers featured a photograph of the valiant Achille Starace jumping headfirst through a flaming hoop.

28