The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (42 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

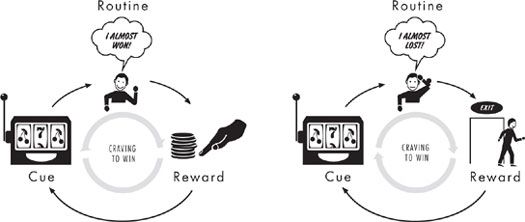

“We were particularly interested in looking at the brain systems involved in habits and addictions,” Habib told me. “What we found was that, neurologically speaking, pathological gamblers got more excited about winning. When the symbols lined up, even though they didn’t actually win any money, the areas in their brains related to emotion and reward were much more active than in non-pathological gamblers.

“But what was really interesting were the

near misses

. To pathological gamblers, near misses looked like wins. Their brains reacted almost the same way. But to a nonpathological gambler, a near miss was like a loss. People without a gambling problem were better at recognizing that a near miss means you still lose.”

Two groups saw the exact same event, but from a neurological perspective, they viewed it differently. People with gambling problems got a mental high from the near misses—which, Habib hypothesizes, is probably why they gamble for so much longer than everyone else: because the near miss triggers those habits that prompt them to put down another bet. The nonproblem gamblers, when they saw a near miss, got a dose of apprehension that triggered

a different habit, the one that says

I should quit before it gets worse

.

It’s unclear if problem gamblers’ brains are different because they are born that way or if sustained exposure to slot machines, online poker, and casinos can change how the brain functions. What is clear is that real neurological differences impact how pathological gamblers process information—which helps explain why Angie Bachmann lost control every time she walked into a casino. Gaming companies are well aware of this tendency, of course, which is why in the past decades, slot machines have been reprogrammed to deliver a more constant supply of near wins.

3

Gamblers who keep betting after near wins are what make casinos, racetracks, and state lotteries so profitable. “Adding a near miss to a lottery is like pouring jet fuel on a fire,” said a state lottery consultant who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity. “You want to know why sales have exploded? Every other scratch-off ticket is designed to make you feel like you almost won.”

The areas of the brain that Habib scrutinized in his experiment—the basal ganglia and the brain stem—are the same regions where habits reside (as well as where behaviors related to sleep terrors start). In the past decade, as new classes of pharmaceuticals have emerged that target that region—such as medications for Parkinson’s disease—we’ve learned a great deal about how sensitive some habits can be to outside stimulation. Class action lawsuits in the United States, Australia, and Canada have been filed against drug manufacturers, alleging that pharmaceuticals caused patients to compulsively bet, eat, shop, and masturbate by targeting the

circuitry involved in the habit loop.

9.25

In 2008, a federal jury in Minnesota awarded a patient $8.2 million in a lawsuit against a drug company after the man claimed that his medication had caused him to gamble away more than $250,000.

Hundreds of similar cases are pending.

9.26

“In those cases, we can definitively say that patients have no control over their obsessions, because we can point to a drug that impacts their neurochemistry,” said Habib. “But when we look at the brains of people who are obsessive gamblers, they look very similar—except they can’t blame it on a medication. They tell researchers they don’t want to gamble, but they can’t resist the cravings. So why do we say that those

gamblers are in control of their actions and the Parkinson’s patients aren’t?”

9.27

On March 18, 2006, Angie Bachmann flew to a casino at Harrah’s invitation. By then, her bank account was almost empty. When she tried to calculate how much she had lost over her lifetime, she put the figure at about $900,000. She had told Harrah’s that she was almost broke, but the man on the phone said to come anyway. They would give her a line of credit, he said.

“It felt like I couldn’t say no, like whenever they dangled the

smallest temptation in front of me, my brain would shut off. I know that sounds like an excuse, but they always promised it would be different this time, and I knew no matter how much I fought against it, I was eventually going to give in.”

She brought the last of her money with her. She started playing $400 a hand, two hands at a time. If she could get up a little bit, she told herself, just $100,000, she could quit and have something to give her kids. Her husband joined her for a while, but at midnight he went to bed. Around 2

A.M.

, the money she had come with was gone. A Harrah’s employee gave her a promissory note to sign. Six times she signed for more cash, for a total of $125,000.

At about six in the morning, she hit a hot streak and her piles of chips began to grow. A crowd gathered. She did a quick tally: not quite enough to pay off the notes she had signed, but if she kept playing smart, she would come out on top, and then quit for good. She won five times in a row. She only needed to win $20,000 more to pull ahead. Then the dealer hit 21. Then he hit it again. A few hands later, he hit it a third time. By ten in the morning, all her chips were gone. She asked for more credit, but the casino said no.

Bachmann left the table dazed and walked to her suite. It felt like the floor was shaking. She trailed a hand along the wall so that if she fell, she’d know which way to lean. When she got to the room, her husband was waiting for her.

“It’s all gone,” she told him.

“Why don’t you take a shower and go to bed?” he said. “It’s okay. You’ve lost before.”

“It’s all gone,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“The money is gone,” she said. “All of it.”

“At least we still have the house,” he said.

She didn’t tell him that she’d taken out a line of credit on their home months earlier and had gambled it away.

Brian Thomas murdered his wife. Angie Bachmann squandered her inheritance. Is there a difference in how society should assign responsibility?

Thomas’s lawyer argued that his client wasn’t culpable for his wife’s death because he acted unconsciously, automatically, his reaction cued by the belief that an intruder was attacking. He never

chose

to kill, his lawyer said, and so he shouldn’t be held responsible for her death. By the same logic, Bachmann—as we know from Reza Habib’s research on the brains of problem gamblers—was also driven by powerful cravings. She may have made a choice that first day when she got dressed up and decided to spend the afternoon in a casino, and perhaps in the weeks or months that followed. But years later, by the time she was losing $250,000 in a single night, after she was so desperate to fight the urges that she moved to a state where gambling wasn’t legal, she was no longer making conscious decisions. “Historically, in neuroscience, we’ve said that people with brain damage lose some of their free will,” said Habib. “But when a pathological gambler sees a casino, it seems very similar. It seems like

they’re acting without choice.”

9.28

Thomas’s lawyer argued, in a manner that everyone believed, that his client had made a terrible mistake and would carry the guilt of it for life. However, isn’t it clear that Bachmann feels much the same way? “I feel so guilty, so ashamed of what I’ve done,” she told me. “I feel like I’ve let everyone down. I know that I’ll never be able to make up for this, no matter what I do.”

That said, there is one critical distinction between the cases of Thomas and Bachmann: Thomas murdered an innocent person. He committed what has always been the gravest of crimes. Angie Bachmann lost money. The only victims were herself, her family, and a $27 billion company that loaned her $125,000.

Thomas was set free by society. Bachmann was held accountable for her deeds.

Ten months after Bachmann lost everything, Harrah’s tried to collect from her bank. The promissory notes she signed bounced, and so Harrah’s sued her, demanding Bachmann pay her debts and an additional $375,000 in penalties—a civil punishment, in effect, for committing a crime. She countersued, claiming that by extending her credit, free suites, and booze, Harrah’s had preyed on someone they knew had no control over her habits. Her case went all the way to the state Supreme Court. Bachmann’s lawyer—echoing the arguments that Thomas’s attorney had made on the murderer’s behalf—said that she shouldn’t be held culpable because she had been reacting automatically to temptations that Harrah’s put in front of her. Once the offers started rolling in, he argued, once she walked into the casino, her habits took over and it was impossible for her to control her behavior.

The justices, acting on behalf of society, said Bachmann was wrong. “There is no common law duty obligating a casino operator to refrain from attempting to entice or contact gamblers that it knows or should know are compulsive gamblers,” the court wrote. The state had a “voluntary exclusion program” in which any person could ask for their name to be placed upon a list that required casinos to bar them from playing, and “the existence of the voluntary exclusion program suggests the legislature intended pathological gamblers to take personal responsibility to prevent and protect themselves against compulsive gambling,” wrote Justice Robert Rucker.

Perhaps the difference in outcomes for Thomas and Bachmann is fair. After all, it’s easier to sympathize with a devastated widower than a housewife who threw everything away.

Why

is it easier, though? Why does it seem the bereaved husband is a victim, while the bankrupt gambler got her just deserts? Why do

some habits seem like they should be so easy to control, while others seem out of reach?

More important, is it right to make a distinction in the first place?

“Some thinkers,” Aristotle wrote in

Nicomachean Ethics,

“hold that it is by nature that people become good, others that it is by habit, and others that it is by instruction.” For Aristotle, habits reigned supreme. The behaviors that occur unthinkingly are the evidence of our truest selves, he said. So “just as a piece of land has to be prepared beforehand if it is to nourish the seed, so the mind of the pupil has to be prepared in its habits if it is to enjoy and dislike the right things.”

Habits are not as simple as they appear. As I’ve tried to demonstrate throughout this book, habits—even once they are rooted in our minds—aren’t destiny. We can choose our habits, once we know how. Everything we know about habits, from neurologists studying amnesiacs and organizational experts remaking companies, is that any of them can be changed, if you understand how they function.

Hundreds of habits influence our days—they guide how we get dressed in the morning, talk to our kids, and fall asleep at night; they impact what we eat for lunch, how we do business, and whether we exercise or have a beer after work. Each of them has a different cue and offers a unique reward. Some are simple and others are complex, drawing upon emotional triggers and offering subtle neurochemical prizes. But every habit, no matter its complexity, is malleable. The most addicted alcoholics can become sober. The most dysfunctional companies can transform themselves. A high school dropout can become a successful manager.

However, to modify a habit, you must

decide

to change it. You must consciously accept the hard work of identifying the cues and rewards that drive the habits’ routines, and find alternatives. You must know you have control and be self-conscious enough to use it—and every chapter in this book is devoted to illustrating a different aspect of why that control is real.

So though both Angie Bachmann and Brian Thomas made variations on the same claim—that they acted out of habit, that they had no control over their actions because those behaviors unfolded automatically—it seems fair that they should be treated differently. It is just that Angie Bachmann should be held accountable and that Brian Thomas should go free because Thomas never knew the patterns that drove him to kill existed in the first place—much less that he could master them. Bachmann, on the other hand, was aware of her habits. And once you know a habit exists, you have the responsibility to change it. If she had tried a bit harder, perhaps she could have reined them in. Others have done so, even in the face of greater temptations.