The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (44 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

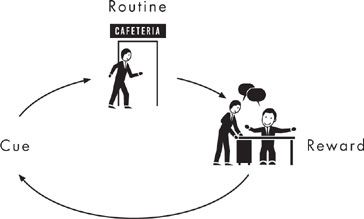

Next, some less obvious questions: What’s the cue for this routine? Is it hunger? Boredom? Low blood sugar? That you need a break before plunging into another task?

And what’s the reward? The cookie itself? The change of scenery? The temporary distraction? Socializing with colleagues? Or the burst of energy that comes from that blast of sugar?

To figure this out, you’ll need to do a little experimentation.

Rewards are powerful because they satisfy cravings. But we’re often not conscious of the cravings that drive our behaviors. When the Febreze marketing team discovered that consumers desired a fresh scent at the end of a cleaning ritual, for example, they had found a craving that no one even knew existed. It was hiding in plain sight. Most cravings are like this: obvious in retrospect, but incredibly hard to see when we are under their sway.

To figure out which cravings are driving particular habits, it’s useful to experiment with different rewards. This might take a few days, or a week, or longer. During that period, you shouldn’t feel any pressure to make a real change—think of yourself as a scientist in the data collection stage.

On the first day of your experiment, when you feel the urge to go to the cafeteria and buy a cookie, adjust your routine so it delivers a different reward. For instance, instead of walking to the cafeteria, go outside, walk around the block, and then go back to your desk without eating anything. The next day, go to the cafeteria and buy a donut, or a candy bar, and eat it at your desk. The next day, go to the cafeteria, buy an apple, and eat it while chatting with your friends. Then, try a cup of coffee. Then, instead of going to the cafeteria, walk over to your friend’s office and gossip for a few minutes and go back to your desk.

You get the idea. What you choose to do

instead

of buying a cookie isn’t

important. The point is to test different hypotheses to determine which craving is driving your routine. Are you craving the cookie itself, or a break from work? If it’s the cookie, is it because you’re hungry? (In which case the apple should work just as well.) Or is it because you want the burst of energy the cookie provides? (And so the coffee should suffice.) Or are you wandering up to the cafeteria as an excuse to socialize, and the cookie is just a convenient excuse? (If so, walking to someone’s desk and gossiping for a few minutes should satisfy the urge.)

As you test four or five different rewards, you can use an old trick to look for patterns: After each activity, jot down on a piece of paper the first three things that come to mind when you get back to your desk. They can be emotions, random thoughts, reflections on how you’re feeling, or just the first three words that pop into your head.

Then, set an alarm on your watch or computer for fifteen minutes. When it goes off, ask yourself: Do you still feel the urge for that cookie?

The reason why it’s important to write down three things—even if they are meaningless words—is twofold. First, it forces a momentary awareness of what you are thinking or feeling. Just as Mandy, the nail biter in

chapter 3

, carried around a note card filled with hash marks to force her into awareness of her habitual urges, so writing three words forces a moment of attention. What’s more, studies show that writing down a few words helps in later recalling what you were thinking at that moment. At the end of the experiment, when you review your notes, it will be much easier to remember what you were thinking and feeling at that precise instant, because your scribbled words will trigger a wave of recollection.

And why the fifteen-minute alarm? Because the point of these tests is to determine the reward you’re craving. If, fifteen minutes after eating a donut, you

still

feel an urge to get up and go to the cafeteria, then your habit isn’t motivated by a sugar craving. If, after gossiping at a colleague’s desk, you still want a cookie, then the need for human contact isn’t what’s driving your behavior.

On the other hand, if fifteen minutes after chatting with a friend, you find it easy to get back to work, then you’ve identified the reward—temporary distraction and socialization—that your habit sought to satisfy.

By experimenting with different rewards, you can isolate what you are

actually

craving, which is essential in redesigning the habit.

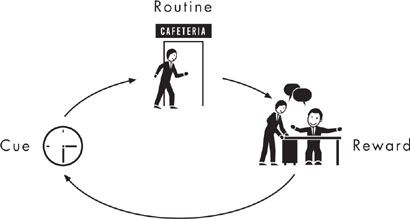

Once you’ve figured out the routine and the reward, what remains is identifying the cue.

About a decade ago, a psychologist at the University of Western Ontario tried to answer a question that had bewildered social scientists for years: Why do some eyewitnesses of crimes misremember

what they see, while other recall events accurately?

The recollections of eyewitnesses, of course, are incredibly important. And yet studies indicate that eyewitnesses often misremember what they observe. They insist that the thief was a man, for instance, when she was wearing a skirt; or that the crime occurred at dusk, even though police reports say it happened at 2:00 in the afternoon. Other eyewitnesses, on the other hand, can remember the crimes they’ve seen with near-perfect recall.

Dozens of studies have examined this phenomena, trying to determine why some people are better eyewitnesses than others. Researchers theorized that some people simply have better memories, or that a crime that occurs in a familiar place is easier to recall. But those theories didn’t test out—people with strong and weak memories, or more and less familiarity with the scene of a crime, were equally liable to misremember what took place.

The psychologist at the University of Western Ontario took a different approach. She wondered if researchers were making a mistake by focusing on what questioners and witnesses had said, rather than

how

they were saying it. She suspected there were subtle cues that were influencing the questioning process. But when she watched videotape after videotape of witness interviews, looking for these cues, she couldn’t see anything. There was so much activity in each interview—all the facial expressions, the different ways the questions were posed, the fluctuating emotions—that she couldn’t detect any patterns.

So she came up with an idea: She made a list of a few elements she would focus on—the questioners’ tone, the facial expressions of the witness, and how close the witness and the questioner were sitting to each other. Then she removed any information that would distract her from those elements. She turned down the volume on the television so instead of hearing words, all she could detect was the tone of the questioner’s voice. She taped a sheet of paper over the questioner’s face, so all she could see was the witnesses’ expressions. She held a tape measure to the screen to measure their distance from each other.

And once she started studying these specific elements, patterns

leapt out. She saw that witnesses who misremembered facts usually were questioned by cops who used a gentle, friendly tone. When witnesses smiled more, or sat closer to the person asking the questions, they were more likely to misremember.

In other words, when environmental cues said “we are friends”—a gentle tone, a smiling face—the witnesses were more likely to misremember what had occurred. Perhaps it was because, subconsciously, those friendship cues triggered a habit to please the questioner.

But the importance of this experiment is that those same tapes had been watched by dozens of other researchers. Lots of smart people had seen the same patterns, but no one had recognized them before. Because there was

too much

information in each tape to see a subtle cue.

Once the psychologist decided to focus on only three categories of behavior, however, and eliminate the extraneous information, the patterns leapt out.

Our lives are the same way. The reason why it is so hard to identify the cues that trigger our habits is because there is too much information bombarding us as our behaviors unfold. Ask yourself, do you eat breakfast at a certain time each day because you are hungry? Or because the clock says 7:30? Or because your kids have started eating? Or because you’re dressed, and that’s when the breakfast habit kicks in?

When you automatically turn your car left while driving to work, what triggers that behavior? A street sign? A particular tree? The knowledge that this is, in fact, the correct route? All of them together? When you’re driving your kid to school and you find that you’ve absentmindedly started taking the route to work—rather than to the school—what caused the mistake? What was the cue that caused the “drive to work” habit to kick in, rather than the “drive to school” pattern?

To identify a cue amid the noise, we can use the same system as the psychologist: Identify categories of behaviors ahead of time to

scrutinize in order to see patterns. Luckily, science offers some help in this regard. Experiments have shown that almost all habitual cues fit into one of five categories:

Location

Time

Emotional state

Other people

Immediately preceding action

So if you’re trying to figure out the cue for the “going to the cafeteria and buying a chocolate chip cookie” habit, you write down five things the moment the urge hits (these are my actual notes from when I was trying to diagnose my habit):

Where are you? (sitting at my desk)

What time is it? (3:36

P.M

.)

What’s your emotional state? (bored)

Who else is around? (no one)

What action preceded the urge? (answered an email)

The next day:

Where are you? (walking back from the copier)

What time is it? (3:18

P.M

.)

What’s your emotional state? (happy)

Who else is around? (Jim from Sports)

What action preceded the urge? (made a photocopy)

The third day:

Where are you? (conference room)

What time is it? (3:41

P.M

.)What’s your emotional state? (tired, excited about the project I’m working on)

Who else is around? (editors who are coming to this meeting)

What action preceded the urge? (I sat down because the meeting is about to start)

Three days in, it was pretty clear which cue was triggering my cookie habit—I felt an urge to get a snack at a certain time of day. I had already figured out, in step two, that it wasn’t hunger driving my behavior. The reward I was seeking was a temporary distraction—the kind that comes from gossiping with a friend. And the habit, I now knew, was triggered between 3:00 and 4:00.

Once you’ve figured out your habit loop—you’ve identified the reward driving your behavior, the cue triggering it, and the routine itself—you can begin to shift the behavior. You can change to a better routine by planning for the cue and choosing a behavior that delivers the reward you are craving. What you need is a plan.