The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (39 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

Extremely satisfied with this paragraph, which said exactly what he wanted it to say, he did something unheard of: this painfully shy man walked around the desk and with an overflowing of camaraderie gave me a hug so huge it left me speechless.

“

B’sede

r

,” he said

–

“OK.”

I kept my appointment with Shimon Peres that afternoon, and I confess that his propensity for hyperbole, poetry, and tautology

–

the very opposite of Yitzhak Rabin

–

got under my skin. He listened patiently when I told him that I felt too great a personal loyalty to Rabin to switch horses overnight, but being the canny and tested politician that he was, he disarmingly brushed off my protestations, and suavely responded that had I been less loyal to Rabin he would have thought less of me.

He then went on to regale me with lyrical and optimistic rhetoric about how he was going to beat Menachem Begin roundly, how Begin was virtually out of the race anyway because of his heart attack, and how all the polls were going his way. And then, taking me by the arm and guiding me toward the door, he said with enormous poignancy, “Yehuda, everything I know tells me I shall be the next prime minister of Israel. Psychologically, I’m living with that responsibility night and day, so it’s only natural I should be thinking now about who I want to work with. And one of the people I want to work with is you. I have lots of new ideas, and you have an important role at my side.” Whereupon, he gave my hand a final squeeze and, full of energy, said, “Get ready for hard work. Expect a call after the victory.”

54

III

The Last Patriarch

1977–1983

August 16, 1913

–

Born Brisk [Brest-Litovsk], Russia.

1935

–

Warsaw University Law School.

1939

–

Head of Betar, Poland (the influential youth wing of the Zionist Revisionist movement founded by Ze’ev Jabotinsky).

1939

–

Marries Aliza Arnold.

1940

–

Sentenced to eight years in Siberian labor camps by Soviet secret police for Zionist activism.

1941

–

Released to join Free Polish Forces following the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union.

1942

–

Arrives in Eretz Yisrael with the Free Polish Forces.

1943

–

Assumes command of the underground

Irgun Zvai Leumi

(The National Fighting Organization).

1944

–

Leads uprising against the British rule of Eretz Yisrael.

Key Events of Political Life

1948

–

Begin disbands the Irgun following Israel’s independence and establishes the Herut (later the Likud) Party.

1967

–

Helps initiate the national unity government on the eve of the Six-Day War.

1970

–

Resigns from the national unity government.

May 1977

–

Elected prime minister.

November 1977

–

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat visits Jerusalem.

1978

–

The Camp David Accords are signed with Egypt, facilitated by President Jimmy Carter.

1978

–

Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

1979

–

Peace treaty with Egypt.

1980

–

‘Operation Moses’

–

the initial covert mass rescue of the black Jews of Ethiopia.

January 1981

–

Ronald Reagan assumes the U.S. presidency.

June 7 1981

–

Israeli air force destroys Iraq’s nuclear reactor.

June 30 1981

–

Begin reelected prime minister.

October 1981

–

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat is assassinated.

June 1982

–

Operation Peace for Galilee.

September 1982

–

The Sabra and Shatila massacre.

November 1982

–

Aliza Begin dies.

February 1983

–

The Kahan Commission report on the Sabra and Shatila massacre.

October 1983

–

Begin resigns the prime ministership and retires from public life.

March 9 1992

–

Begin dies at the age of 79.

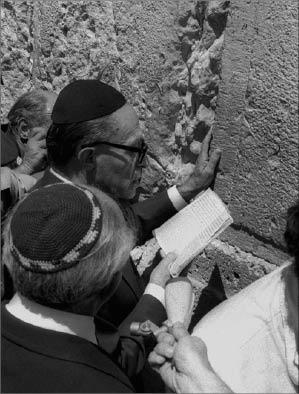

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Designate Menachem Begin praying at the Western Wall upon receiving the mandate to form the new government, 7 June 1977

Upheaval

At eleven o’clock in the evening of 17 May 1977, I was sitting cross-legged in front of the television in the company of my wife and four kids, listening to the station’s chief anchorman, Chaim Yavin, repeating for the umpteenth time the word

“

Mahapach!

”

–

Upheaval!

–

and breathlessly announcing that according to the television’s sample poll Menachem Begin, leader of the opposition Likud Party, had roundly trounced Labor’s Shimon Peres in the elections that day.

“I don’t believe it,” I cried out in disbelief. “Peres just offered me a job.”

The phone rang. It was General Freuka Poran. In a supercharged voice, he snarled, “Are you watching the

tv

? Look at them

–

those Beginites. They’re our new bosses. Ever since I was a youngster in the Hagana I’ve been allergic to that man and his minions. He’s a”

–

his voice climbed

–

“he’s a ghetto windbag, an ex-terrorist, a fanatic!”

“Cut it out,” I shot back.

“I won’t work for him,” he shouted.

“But you’re a soldier,” I said angrily. “You can’t opt out because of a political whim. Are you telling me you’re not going to follow the orders of the next prime minister of Israel, which apply to me”

–

he knew about my last talk with Rabin

–

“and which apply to you even more so, General Poran?”

He shot back, feisty as hell. “Do they? Well let me tell you

something

. This is no whim. That man is going to lead us into war, and I want no part of it. I’m quitting the army.

Layla tov!

” [Good night!] And he hung up.

I went back to join my family, who remained transfixed by the political theater filling the screen. It showed the hall at Begin’s party headquarters in Tel Aviv where hundreds of loyalists were applauding in incredulity and ecstasy, all bellowing in a single voice, “BE-GIN! BE-GIN! BE-GIN!” The din was so ear-battering that the jostled television reporter on the floor had given up trying to describe what the clamor was about. But then, as we watched, he cupped his hand around his microphone and yelled for all he was worth, “Here he comes! He’s coming now,” and the camera zoomed in on the prime minister–elect entering the hall, crowded in on every side. Despite the grainy picture on our black-and-white screen, the signs of his recent heart attack were distinct. His face was sallow, his cheekbones were pronounced, his semi-bald crown was thrown into prominence. Yet his ravaged features were animated by a dazzling smile as he moved with obvious joy into the shoe-stomping, raucous throng crushing in upon him on every side. And as he moved, the thrilled assembly chorused his name ever louder:

“BE-GIN! BE-GIN! BE-GIN!”

Anxious guards, stewards, aides, and policemen pushed and elbowed the adoring crowd, cutting a channel through the crush to let the victor enter. Inching his way toward the stage, Begin waved with both hands high, and when he finally mounted the platform, the entire jamboree exploded into the thumping patriotic chant,

Am Yisrael Chai

–

The People of Israel Live.

His figure was all aglow in camera flashes as he led the throng, clapping his hands and bending his knees up and down to the rhythm of the beat, like a Chasidic rabbi.

Swiftly seizing the opportunity as the champion raised his palms to quell the applause, the television commentator explained that Menachem Begin was sixty-three, and had been in Israel for thirty-five years.

The singing and shouting gradually settled into a deep hush, and those pressing around the prime minister-elect peeled aside to give him center stage, leaving him standing alone beneath the giant portraits of his two ideological heroes, Theodor Herzl and Ze’ev Jabotinsky. And there he stood, isolated in the stillness, drinking in the crowd’s adoration, a slender, frail-looking figure in a dark suit, his face pale yet his eyes bright.

With deep reverence, he drew from his pocket a black yarmulke and recited the

Shehecheyanu

blessing, thanking the Almighty for enabling him to reach and celebrate this day. A resounding “Amen!” roared around the hall with such energy it caused the microphone to shriek with feedback. Next Begin recited a psalm of gratitude, and, after that, his victory address, an oration of reconciliation, in which he appealed for a spirit of national unity, capping his address with the compelling phrases of Abraham Lincoln: “With malice toward none; with charity to all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive to finish the work we are in.”

As the applause swelled again, Menachem Begin turned toward his wife, Aliza, a petite woman with springy gray hair and thick glasses, wearing a simple gray suit, who all this while had been standing modestly behind him. One could see the embrace in his eyes as he told her, in a voice husky with emotion, of his eternal love and his everlasting debt toward her, for the way she had stood by him through thick and thin, in unbounded devotion and sacrifice, for forty years.

“I remember you, the kindness of your youth,” he lauded, quoting the Prophet Jeremiah. “I remember you, the love of your betrothal, when you followed me into the wilderness, into a land that was not sown.” And then, paraphrasing, “I remember you when you followed me into a land that was strewn on every side with deadly minefields, and yet you followed me.”

These deeply passionate feelings spoken so openly stood in such sharp contrast to Yitzhak Rabin’s famed emotional austerity that they triggered shouts of approval from the entire assembly. The clapping and the whistles went on for so long that many probably missed Begin’s invocation of the memory of his “master and teacher,” Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the charismatic nationalist ideologue, founder of the Revisionist Zionist Movement, in whose footsteps he devoutly walked.

“Prodigious and startling were Ze’ev Jabotinsky’s gifts,” he declared. “He was decades ahead of his time, a giant Zionist warrior-statesman, a true prophet of his people, the man who led the movement for the settlement of the whole of biblical Israel, who was the first to sound the alarm of the coming holocaust, and the war cry for a Jewish army to fight for freedom and a sovereign Jewish State.”

Ending with a promise to fulfill Jabotinsky’s legacy, he bowed low, and the whole hall rose to chant the anthem of national hope,

“

Hatikva

.” People pumped hands and hugged each other, not wanting the moment ever to end, even though it was three in the morning. But end it did, and Begin, shielded once more by a cordon of security personnel and officials, waved his way off the platform, beaming, shaking every palm he could reach and kissing the knuckles of every woman who thrust her hand at him, with all the gallantry of a Polish peer.

55

Instantly, the camera shifted to the floodlit street outside, where loudspeakers blared patriotic music and devotees milled around singing and dancing under blue and white paper bunting. Men and women of every age were there, from youngsters to oldsters, most of them olive-skinned. They originated from places like Morocco, Tunisia, Yemen, Iraq, Libya, Kurdistan, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, and India. Commentators would later explain that it was they, these Oriental immigrants, who had catapulted Menachem Begin into power after almost thirty years in the political wilderness. They were the impoverished and the God-fearing, Sephardic Jews mainly, who, having felt left out and passed by, fed up of slum life and handouts, had finally flexed their muscles, put their energy behind Mr. Begin, and settled their score with the paternalistic and elitist European Labor old-timers of whom Shimon Peres was the epitome.

Scores gathered eagerly around a television commentator who had thrust his microphone into their faces.

“Why did you vote for Menachem Begin?” he asked. “What makes him so different from Shimon Peres? Peres’ name was originally Perski. Both were born in Poland. Is not Begin as much an Ashkenazi as Peres?”

“Ashke-NAZI!” yelled somebody off-camera.

“Shut up!” bellowed a man with the sloped shoulders of a boxer, dressed in a waiter’s jacket. “You want to know why we voted Begin? We voted Begin because he’s not a godless socialist like Shimon Peres and his atheist lot. Begin never lined his pockets the way they have. He’s humble and honest. Begin speaks like a Jew, the way a Jew should speak. He’s not ashamed to say ‘God.’ He speaks with a Jewish heart. That’s why Labor always ridiculed him, and treated him the way they always treated us

–

like scum.”

“Are you saying that Peres and the entire secular Labor crowd are not really Jews?” asked the interviewer, provocatively.

The man spat. There was contempt in his eyes. “They may be Jews, but they behave like goyim. Have you ever seen one of them inside a

beit knesset

–

a synagogue? What’s a Jew without a synagogue sometimes? Where’s their self-respect, their pride?”

“

Ya, habibi

,” cut in someone else, sporting a thick crown of greased black hair, also wearing a waiter’s jacket. “Thirty years ago those Labor bigwigs duped us. They brought us here telling us this was the

Geula

, the Redemption. Cheap labor, that’s what they brought us here for. In Casablanca my father was an honored member of the community. He was the patriarch of our family. He had

kavod

–

respect.”

“

KAVOD!!

” the crowd chorused in corroboration.

“Everybody gave him

kavod

because he ran his own spice shop in the Kasba. Now what does he do? He breaks his back on a building site. Who’s going to give him

kavod

now? In Morocco only Arabs work on building sites. His

kavod

has been stolen.”

Heads nodded vigorously.

“What’s your name?” asked the interviewer.

“Marcel.”

“So, tell us Marcel, what did you do in Casablanca?”

“I was a bookkeeper. That’s an occupation of

kavod

. Now I’m a waiter. In Morocco, only Arabs are waiters. In Casablanca we lived in a big house with a courtyard. Now, I, my wife, my three children, my mother, my father

–

all of us live in four ramshackle rooms. Our

kavod

has been trampled upon. The Ashkenazi Labor bosses did that. And now Menachem Begin is giving us our

kavod

back.”

He said this in such a triumphant tone that one man began jumping up and down in front of the camera, clapping his hands in excitement and shouting something in a Moroccan Hebrew I could not understand. Other people cheered and burst forth into a rousing singsong. Spontaneously, they formed a chain, hands on each other’s shoulders, and ecstatically weaved around and about, singing at the tops of their voices,

“

Begin, Melech Yisrael

”

–

Begin, King of Israel.

This, assuredly, was their field day. To them

–

half of Israel’s population

–

the name Menachem Begin had an almost mystical appeal. Without sycophancy or pretense, he had won their hearts, knocking down the high walls of arrogance and sectarianism which had cut them off from mainstream Israel since their mass immigration two and three decades before. Ever since national independence, and long before that as well, the country had known only one ruling party

–

Mapai, the Labor Party

–

and it saw itself as an all big-guns political battleship designed to rule the political seas forever. But it went off course and was caught off guard by a vessel captained by Menachem Begin who, running silent, running deep, rose incrementally from election to

election –

from

fifteen

, to seventeen, to twenty-six, to thirty-nine

–

until he surfaced with a spectacular showing in the battle of 1977 with the largest number of Knesset seats of any single party, forty-three: enough to form a coalition.

The shocked Laborites drew up petitions, held meetings, organized protests, made speeches, wrote articles, and convened conferences. Many insisted that their downfall was really the fault of President Jimmy Carter. He had publicly tilted toward the Arabs. He had publicly challenged Yitzhak Rabin. He had publicly produced what was tantamount to a

unilateral

peace plan. He had stabbed Labor in the back by making nonsense of the accepted axiom that they, and they alone, with their vast experience in international affairs, could win and retain the trust of the White House and the American people. But at the end of the day, the truth was much simpler. Labor lost because it had defeated itself. It had been in office for far too long. Its blood was tired and its rank and file flabby.

This was why much of the nation was ready to give Menachem Begin his chance. His integrity shone through. Even his opponents acknowledged his modest, almost monastic lifestyle, and his strict personal uprightness. So, many a moderate gave him the vote as well, on the assumption

–

and in the hope

–

that the burdens and realities of office would mellow his passionate vow never to surrender a single inch of the beloved

moledet

–

the biblical homeland: Eretz Yisrael. And so they, too, dumped Labor and with the untested Begin at the helm, slipped the national anchor from its familiar moorings, and pushed off on an untutored course into uncharted waters.

Cables from our Washington Embassy reported dismay at Menachem Begin’s victory. Some of President Carter’s aides suggested he snub the prime minister-elect by not inviting him to Washington. After watching a Begin interview on

ABC

’s

Issues and Answers

, Jimmy Carter was so aghast at what he heard that he wrote in his diary on 23 May 1977:

I had them replay the

Issues and Answers

interview with Menachem Begin, chairman of the Likud Party and the prospective prime minister of Israel. It was frightening to watch his adamant position on issues that must be resolved if a Middle Eastern peace settlement is going to be realized…. In his first answer he stated that the entire West Bank was an integral part of Israel’s sovereignty, that it had been ‘liberated’ during the Six-Day War, and that a Jewish majority and an Arab minority would be established there. The statement was a radical departure from past Israeli policy, and seemed to throw United Nations Resolution 242, for which Israel had voted, out of the window. I could not believe what I was hearing.

56

The international media pilloried Begin;

Time

magazine even headlined its election story with an anti-Semitic slur: “BEGIN (rhymes with Fagin) WINS,” and the London

Times

led its comment on the election result with the Roman proverb: “Whom the gods want to destroy, they first drive them mad.” Prominent Diaspora community leaders, unused to any Israeli leadership but the pragmatic Laborites, were startled at Begin’s electoral success and urged him to moderate his public statements, particularly on settlement policy. The day after his victory, Begin had traveled to an

IDF

encampment called Kaddum, near Nablus, in the heart of the densely Arab populated hill country, and in the course of an impromptu press conference announced a settlement drive to embrace the whole of the West Bank, which he insisted on calling by its biblical name – Judea and Samaria.