The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (43 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

And, as a Jew, he loathed violence. Terrorism of any kind, for whatever noble a goal, was abhorrent. In the 1960s he had condemned the French for their brutal war of counterinsurgency against the Algerians, and then had condemned the Algerian

FLN

for their counterterrorism against French civilians. So how could he shake the hand of Menachem Begin who, in 1946, had ordered this very hotel to be blown up, which resulted in the loss of ninety lives?

I cut in to insist that there were different versions of that old episode, but he kept on going at such a helter-skelter pace he could not have heard me. Only when I raised my voice to argue that, at the end of the day, we Israelis had democratically elected our own prime minister in a free and secret ballot, did he pause to concede: “Well, yes, that’s true. Besides, who am I to offer you people advice? You would never want to accept it anyway. I’m no better understood in the Jewish State than I am in other places. As often as I come here, I don’t know if I understand Israel at all. I don’t know how many Jews in the Diaspora really understand Israel. I don’t know how many Israelis understand the Diaspora, for that matter.”

With this thought, he fumbled with a tiny magnifying glass that was dangling on the end of a chain from his vest pocket, placed it close to his eyes to check his watch in the dim light of the bar, and apologized that he had to run.

“So do I,” I said.

I took the elevator up to the prime minister’s suite on the sixth floor, knocked, and was greeted by a smiling Mrs. Begin, who beckoned me inside with a motherly invitation to have a cup of coffee.

“Ah, there you are,” called the prime minister, detaching himself from his guests and extracting the letter to President Carter from his pocket. I began to apologize for my tardiness, but he apologized back, handing me the letter and saying, “I’m sorry it’s so crumpled. There were so many hands to shake when I walked into the hotel lobby I inadvertently stuffed it into my pocket.”

He drew me into the lounge to introduce me to his guests

–

a half dozen middle-aged, extremely well-dressed couples, talking to each other in an admixture of Yiddish, Polish, and English. They had the look of affluent Holocaust survivors, from America.

“I was just talking to my friends here about Sir Isaiah Berlin,” said Begin, sardonically.

“Stop taking it to heart, Menachem,” chided Mrs. Begin. “For more than thirty years you’ve had so many people turn their backs on you, and suddenly you’re surprised that some still do. Sit down. Relax. Try one of these.” She proffered a tray of rolls, pastries, and cookies, together with a glass of steaming tea.

“Sir Isaiah has, of course, an extraordinary mind,” granted Begin, seating himself on a couch surrounded by his admirers. Between a sip of tea and a nibble of a cookie, he continued, “As a philosopher, he’s a genuinely original theorist. But as a Zionist thinker he’s a…”

–

a rascally look lurked in his eyes

–

“he’s a

J.W.T.K

.”

“A what?”

“A Jew with trembling knees.”

The people around him laughed.

“Those utopian Zionists like Berlin wove a fantasy that bewitched the Zionist movement for decades,” continued Begin, in a voice that had gone absolutely earnest. “Had we followed the Isaiah Berlin path we would never have had a Jewish State. Their flight of fancy led them to the delusion that the Arabs would eventually come to terms with us for the sake of their economic progress. What utter nonsense! Ze’ev Jabotinsky had too much respect for the Arabs to believe they would come to the peace table for the sake of a mess of pottage.”

The mention of Jabotinsky’s name prompted a number of these old Revisionists to begin reminiscing about their late leader with all the adoration of disciples. I, standing on the periphery, heard Menachem Begin muse about his “master and teacher,” as though he were a prophet. He reminded his guests how Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionism was the only unblinking realism in the crumbling Jewish world that ended in the Holocaust. He was the first to warn against the coming European catastrophe; the first to organize illegal rescue boats to Eretz Yisrael; the first to sound the warcry for a Jewish army; the first to maintain that we have to fight for a Jewish State; the first to advocate the building of an ‘iron wall’ of deterrence that would ultimately convince the Arabs that they had no alternative but to come to terms with a Jewish State.

“Ze’ev Jabotinsky foresaw this ‘iron wall’ doctrine already in the twenties,” concluded Begin. “And ultimately, it was to become the strategic imperative of all of Israel’s leaders. What are the Israel Defense Forces if not an iron wall? Surely, few men have been so vindicated by history.”

I deemed this an appropriate moment to take my leave and ready the prime minister’s letter for dispatch to the American president. And as I did so, the thought occurred to me that what I had just witnessed was high drama

–

Begin and Berlin: two extraordinary men, perfectly representing the warring sides of the Jewish character and the contradictory visions of the Jewish narrative and Jewish survival.

An echo of this was reflected in the contents of the letter to the president, which read:

Dear Mr. President,

Thank you for your warm letter of congratulations. My colleagues and I are deeply grateful for your wishes for the success of the new government of Israel. On May 17 our free people decided by the ballot upon a change of administration. Since then, three acts took place in accordance with our constitution. The president of the republic charged me with the task of forming a new government. The Knesset expressed its confidence by a majority vote in the government presented to our parliament. My colleagues and I took in the House the oath of allegiance to our country and to its constitution.

Proof has been given that liberty and democracy reign in our land. Transfer of power took place in a most orderly way. We have learned much from the dignified manner in which such transfer was carried out in the United States.

Mr. President, with all the differences in might between our country and the United States of America I share your view that both nations have much in common. Lofty ideas of humanity, democracy, individual liberty and deep faith in Divine Providence are the cherished heritage of the great American people and the renascent Israel. May I assure you, Mr. President, that the friendship between our countries is, and always will be, the foundation of our policy reflected in our special relationship and based also, as I believe, on the recognition of a community of interests.

The people of Israel seek peace, yearn and pray for peace. It is therefore natural that as Israel’s elected spokesmen, my colleagues and I will do our utmost to achieve real peace with our neighbors. It is in this spirit that I gratefully accept your invitation to visit your great country during the week of July 18th and I look forward to meeting with you and to have a most fruitful exchange of views with the president of the United States who is also the leader of the free world. With my best wishes,

Sincerely

M. Begin

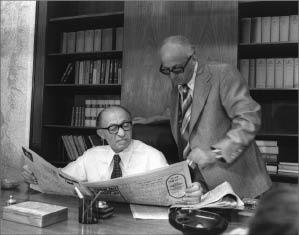

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Begin scans the morning papers with lon

g-tim

e aide Yechiel Kadishai, 21 June 1977

Yechiel and Begin

Compared to the efficiency of the bureaus of the previous prime ministers I had served, Menachem Begin’s was a bit chaotic. Yechiel Kadishai, who ran it, was in a constant whirl of banter, ideas, deliberation, and good deeds. Forever amiable, Yechiel had no head for systematic planning and staff work. He delegated to a fault. Nevertheless, as hectic as the bureau could be, he ran it with a remarkable flair for improvisation and a gift for divining the location of any document the prime minister might require. People of every sort

–

down-and-outs, immigrants, fans, journalists, politicians, charlatans

–

were constantly in and out of his open door. On one occasion, a week or so after I had adjusted to his pulse, a bedraggled-looking fellow in a battered trilby and tattered raincoat walked out of Yechiel’s office just as I was about to walk in. I recognized him; he was a peddler in downtown Jerusalem.

“What’s that hawker doing here?” I asked. “Do you know him?”

“Sure. His name is Kreisky.”

“Who?”

“Shaul Kreisky, brother of the chancellor of Austria, Bruno

Kreisky

.”

Yechiel’s face remained totally deadpan as he said this, and my mouth dropped open as I watched the visitor shuffling down the corridor toward the exit. Could he really be the brother of the Austrian chancellor whom Golda Meir had hauled over the coals because he had surrendered to Arab terrorist blackmail?

“You’re pulling my leg!” I said.

“No, I’m not,” answered Yechiel. “He’s lived here for years. The prime minister occasionally helps him out. He’s a great admirer of Begin. Run after him and ask him.”

I did. It was absolutely true.

The trappings of rank interested Yechiel Kadishai not one bit. He refused a car and driver, which were his due, and opted instead to travel to Jerusalem from his Tel Aviv home on an early bus, often at sunrise. Predictably, he and his wife Bambi were now on everyone’s invitation list, and he had the enviable ability to walk into a room filled with strangers, confident he would walk out of it having made a sourpuss smile and a cold fish laugh. At one diplomatic reception soon after he was installed in his new job I watched him turn his irrepressible bonhomie on a cluster of stiff ambassadors, diverting them with the tale of when he first set eyes on Menachem Begin. It had been in 1942, in a Tel Aviv basement, empty but for plain wooden benches on which everyone sat. A meeting of Betar and Irgun members was in progress, most of them volunteers in the special Palestine regiment of the British Army. They were gathered to hear a talk on the fate of the Jews of Europe. Rumors of their mass slaughter were already beginning to circulate.

“In walked a sallow-looking fellow dressed in an ill-fitting British army uniform and wearing John Lennon glasses,” recounted Yechiel. “He wore army-issue short baggy pants down to his knees, and a forage cap with a Polish eagle stuck into it, symbol of the Free Polish Forces in Exile. When he asked for the floor, he said, plain and simple, that the only way to save European Jewry was to compel the British to quit Palestine as quickly as possible and then open the country’s gates to free immigration. I asked people who this fellow was and they told me his name was Menachem Begin, and that back in Poland he’d been head of the Betar movement

.

I’d never heard of him before.”

Yechiel then went on to relate how, over the course of the following two years, he had served in the Western Desert and in Europe, and it was while doing duty in the European displaced persons camps that he heard that Menachem Begin had been appointed commander of the Irgun underground.

“What exactly were your duties in the camps at that time?” asked one of the diplomats.

“Smuggling,” answered Yechiel artlessly. “King George’s uniform did wonders for my tricks as a smuggler.” He declared this with such irreverence that a couple of the ambassadors threw their heads back in great peals of laughter, while others cast him startled stares.

“What on earth were you smuggling? Or is that too delicate a question?” asked one.

“Death camp survivors, across frontiers to southern ports for so-called ‘illegal immigration’ to Eretz Yisrael,” Yechiel shot back. He then went on to tell them how he himself had returned home in the summer of 1948 on the illfated Irgun ship, the Altalena, only to be fired upon on arrival by fellow Jews.

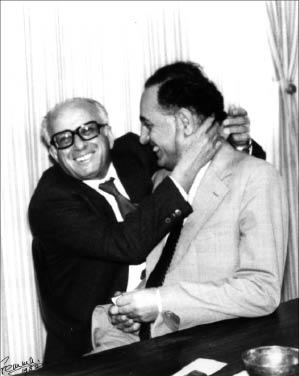

Photograph credit: Gemma Levine, London, UK

Yechiel Kadishai and author, November 1978

“And after that?” queried another.

“After that I began working on behalf of families of the Irgun fallen and the wounded. In those early days our ministry of defense discriminated against our people in favor of the former Hagana fighters. However, I discovered a number of fair-minded sorts working in the ministry and they helped me out. It was during the course of that work that I came to Mr. Begin’s attention, and I began working for him in sixty-four. I haven’t stopped since.”

Later, among themselves, or so I was told, the ambassadors discussed Kadishai’s natural exuberance. One of them, claiming private knowledge, said that loyalty meant more to Begin than ability. All concurred that the two men were inseparable, Kadishai having been unswervingly loyal during Begin’s solitary years in the political wilderness of opposition, during which he suffered eight consecutive electoral defeats. Kadishai, they concluded, was the man to cultivate.

I learned quickly that Yechiel had an intuitive ability to anticipate Begin’s every wish, as though they communicated telepathically. Yechiel was the one person outside the family with whom Begin could totally unwind. With him he could share both confidences and casual chitchat. Yet even Yechiel’s natural gusto tended to subside into a restrained reverence whenever he entered Begin’s presence, and this proved true of all of Begin’s old-time underground fighters. He still expected absolute obedience. Daily, I noted how these veterans related to him with a fidelity that bordered on total submission. To them, he was a patriarch.

“Sure, he’ll sometimes ask my opinion, but that’s usually to

convince

me of the correctness of his own,” Yechiel once confided to me. “Most of the time we understand each other without talking.”

This made him invaluable as chief of the prime minister’s bureau. Yechiel knew who to recommend for positions of influence in the sure knowledge that Begin would approve them; he would soften up Knesset bigwigs and party ringmasters before they entered the prime minister’s presence; while absenting himself from meetings he would know exactly who said what to whom; he arranged the prime minister’s visitors’ schedule without having to consult him; and he intercepted and deflected those he knew Begin would not want to see.

As for the prime minister himself, for one who had recently suffered a heart attack, his day was jam-packed. Up at dawn, he would start his day’s work with a glass of lemon tea and a survey of the news. He would listen to the

BBC

on the radio, read all the major dailies with intense concentration, occasionally making notes, and committing the papers’ contents to his photographic memory. Next was a perusal of the foreign press. Then he would look over any documents he was currently dealing with, eat a light breakfast, make a few calls to cabinet colleagues, and arrive at the office by eight. There, he studied the overnight cables, sat with his staff for briefings and issued instructions, and then he would move from his desk to the lounge corner of his office, where he received a steady flow of callers. He would go home for lunch with his wife at one without fail, which he followed with a nap, and a return to the office at three thirty. He stayed until six. The last hour was usually spent dictating and signing letters, after which he would review the forthcoming day’s schedule, bid a personal goodnight to each of his secretaries, and exit the building in the company of Yechiel, who would hand Begin’s briefcase to the head of his security squad. The briefcase contained two files, one relating to domestic affairs, the other to defense and foreign affairs.

Most evenings were taken up with public engagements, at the end of which the prime minister would ascend the stairs to his private quarters, study the two sets of files at the kitchen table over a final glass of lemon tea, retire to bed with a book, and be up four or five hours later to start the next day afresh.

Although Begin took pride in thinking of himself as first among equals, he ruled his cabinet with a rod of iron. His opening words at the inaugural meeting were “There shall be no smoking!” He then insisted his ministers pay due respect to the Knesset by attending whenever it was in session

–

most particularly on Mondays and Tuesdays, when much of the parliamentary work was done.

Grunts of objection rolled around the table. They were cut short when the prime minister asked for silence so that he could give them a piece of his mind.

“We have to restore the dignity of the Knesset to our national life by improving our attendance,” he admonished. “It is shameful that the public see a virtually empty chamber every time they switch on their television sets. If we cabinet members set an example, the rest of the Knesset will follow.”

Defense Minister Ezer Weizman whispered to Agricultural Minister Ariel Sharon, “It’s a crazy idea! It won’t work!” A look from the prime minister told Weizman he had been heard, and the former commander of the air force muttered a request for forgiveness. Moshe Dayan passed Begin a note that prompted the prime minister to pause and say, “The foreign minister thinks my request is not feasible, since it will leave you too little time to run your ministries. I therefore accept his recommendation, that you divide your Knesset attendance equally between you

–

half of the cabinet to attend on Mondays and half on Tuesdays.”

The sigh of relief over the reprieve was palpable.

Compared to the temper of Rabin’s cabinet ministers, Begin’s were meek. Rabin had Peres to contend with; he had to watch his back. Not that this was unusual in Labor circles. Labor cabinets were invariably cacophonous, punctured with caustic leaks and acerbic blasts. Labor leaders were for the most part a single-minded, disputatious lot

–

trade unionists, kibbutzniks, party strongmen

–

united by an adherence to the socialist creed, but fractured by its multiple nuances. Internecine warfare was the norm, each leader creating his own camp followers, and each wheeling and dealing behind the others’ backs. In contrast, the new Likud cabinet, with its one commanding, charismatic figure in the chair, was disciplined and leakproof, at least to start off with.

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

Prime Minister Begin chatting with his foreign minister Moshe Dayan, 20 June 1977

Lack of leaks drove the media to distraction, particularly when the prime minister was preparing himself for his first meeting with the American president, and every official mouth was tight-lipped. Menachem Begin knew that to Jimmy Carter and his chief advisers

–

National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance

–

the paramount element of the Middle East dispute was not so much the enmity of the Arab states, threatening though that was, but the Palestinian question. Solve the Palestinian question, they contended, and you have the key to peace. This was Carter’s ambition

–

a comprehensive settlement to be achieved through a Middle East peace conference at Geneva, with a Palestinian representation at the table. To this end he had already met most of the Arab heads of state, and we anticipated that this president would readily ignore the earlier Ford-Kissinger pledge to keep Arafat and his

PLO

out of the process as long as they did not recognize Israel’s right to exist. Moreover, we assumed that if and when Begin launched his promised settlement drive in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, the chances were that Israel would risk not merely U.S. reprimand, but perhaps U.S. economic and military sanctions, too. Indeed, by one official estimate, “The vastly differing approaches of Begin and Carter reveal a philosophical chasm that may prove impossible to bridge, and unless a mutually acceptable formula is found, the times ahead could be so abrasive as to bring the U.S.-Israeli relationship to its lowest ebb since the establishment of the state.”

Meanwhile, a new American ambassador had come to town and was making the rounds. Houston born, and a Yale man, Samuel Lewis was a career diplomat with a great deal of experience, self-confidence, a sense of humor, and an open mind. Over our first cup of coffee he told me with absolute candor

–

clearly for Begin’s ears

–

that the president was very impatient to get his Middle East diplomacy going, and that he would not shrink from being ‘confrontational’ if that was what it would take to make it happen. With equal candor, he confided, “I’ve informed Washington that Mr. Begin needs careful handling, and honey is going to get us a lot further than vinegar. I’m flying ahead to Washington in the hope of cooling things down a bit.”

The prime minister made no comment when I reported this to him. He was devoting every spare waking hour to planning his own pitch with the president. Again and again he pored over the protocols of the March Rabin-Carter clash, and read and reread the entire file of the president’s declarations on the Middle East. Almost daily, he sat with his senior ministers to finesse Israel’s position on the convening of a Geneva peace conference. At one such meeting he summed up his feelings about the American president: