The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership (51 page)

Read The Prime Ministers: An Intimate Narrative of Israeli Leadership Online

Authors: Yehuda Avner

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #Politics

“And in what sense do you find that objectionable?”

“In the sense that we, the Jewish people alone, are responsible for our country’s survival, no one else.”

Wordlessly, and seemingly perplexed, the national security adviser deleted the offensive sentences, upon which the prime minister expressed himself totally satisfied.

65

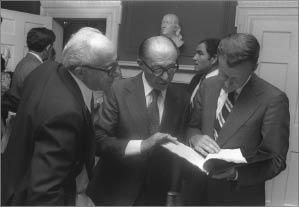

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office

Nat. Sec. Adviser Brzezinski examines the portfolio of his father's rescue efforts of German Jews in the 1930s, presented to him by Prime Minister Begin, with Yechiel Kadishai looking on, 20 July 1977

To Ignite the Soul

As previously arranged, after the White House talks I returned to New York to call upon the Lubavitcher Rebbe and report to him on how we had fared. There, at 770 Eastern Parkway, I found myself settled with the sage in his unadorned wood-paneled chamber, where he greeted me with a beaming smile. Dog-eared Talmudic tomes and other heavy, well-thumbed volumes lined his bookshelves, representing centuries of scholarship and disputation.

We spoke in Hebrew; the Rebbe’s classic, mine modern. What lured me most as we talked were the Rebbe’s eyes. They were wide apart, sheltering under a heavy brow, but fine eyebrows. Their hue was the azure of the deep sea, intense and compelling, although I knew that when the Rebbe’s soul turned turbulent, they could dim to an ominous grey, like a leaden sky. They exuded wisdom, awareness, kindness, and good fellowship; they were the eyes of one who could see mystery in the obvious, poetry in the mundane, and large issues in small things; eyes that captivated believers in gladness, and joy, and sacrifice.

As he dissected my account, his air of authority seemed to deepen. It came of something beyond knowledge. It was in his state of being, something he possessed in his soul which I cannot possibly begin to explain, something given to him under the chestnut and maple trees of Brooklyn rather than under the poplars and pines of Jerusalem to which, mysteriously, he had never journeyed.

I never asked him why, because I felt that he dwelt on an entirely different plane

–

a profoundly mystical plane, one to which I, a mere diplomat, could never aspire. The Lubavitcher Rebbe was a theologian, not a political Zionist. But if Zionism is an unconditional, passionate devotion to the Land of Israel and to its security and welfare, then Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson was a fanatical Zionist.

My presentation, his interrogation, and his further clarification took close to three hours. By the time we finished it was nearly two in the morning. I was utterly exhausted, but not the Rebbe. He was full of vim and vigor when he said, “After listening to what you have told me I wish to communicate the following message to Mr. Begin,” and he began dictating in a voice that was soft but touched with fire:

“By maintaining your firm stand on Eretz Yisroel in the White House you have given strength to the whole of the Jewish people. You have succeeded in safeguarding the integrity of Eretz Yisroel while avoiding a confrontation with the United States. That is true Jewish statesmanship: forthright, bold, without pretense or apology. Continue to be strong and of good courage.”

Then to me:

“What do I mean when I say to Mr. Begin, ‘Be strong and of good courage?’ I mean that the Jewish people in Eretz Yisroel cannot live by physical power alone. For what is physical power? It is made up of four major components: One

–

weaponry: do you have the weaponry to assert your physical power? Two

–

will: do you have the will to employ your weaponry? Three

–

competence: do you have the competence to employ your weaponry effectively? And four

–

perception: does the enemy perceive that you have the weaponry, the will, and the competence to effectively employ your physical power so as to ensure your deterrent strength?”

And then, gently, “But even if you have all of these, Reb Yehuda, but you are bereft of the spirit of

‘

Mi hu ze Melech hakavod? Hashem izuz v’gibor, Hashem gibor milchama

’ [Who is the King of glory? The Lord strong and mighty, the Lord mighty in battle] then all your physical power is doomed to fail, for it has no Jewish moral compass to sustain it.”

At this his usually benign features became grim, and his eyes dimmed to an ominous gray when he added, “For in every generation an Amalek rises up against us, but the

Ribono shel Olam

[the Almighty] ensures that every tyrant in every age who seeks our destruction is himself destroyed.

Am Yisrael chai

[the people of Israel lives on] only by virtue of

hashgocho

[divine protection]. Time and again, our brethren in Eretz Yisroel have been threatened with destruction. Time and again they have floundered and stumbled and been bled. Yet time and again,

b’siyata d’Shamaya

[with the Almighty’s help] they have weathered every storm, overcome every hurdle, withstood every test and, at the end of the day, emerged stronger than before. That is

hashgoch

o

.”

Relaxing, he fixed me with those eyes, and with a surprisingly sweet smile, said, “Now tell me, Reb Yehuda, you visit us so often yet you are not a Lubavitcher. Why?”

Still trying to absorb what he had said, I sat back, stunned at the directness of the question. It was true. This, probably, was my fifth or sixth meeting with the Rebbe. Over the years I had become a sort of unofficial liaison between the various prime ministers I served and the Lubavitch court.

Swallowing thickly, I muttered, “Maybe it is because I have met so many people who ascribe to the Rebbe, powers which the Rebbe does not ascribe to himself.”

Even as I said this I realized I had presumed too much, and I could hear my voice trailing away as I spoke.

The Rebbe’s brows knitted, and his deep blue eyes grayed again, into something between solemnity and sadness, and he said,

“

Yesh k’nireh anashim hazekukim l’kobayim

” [There are evidently people who are in need of crutches]. The way he said it conveyed infinite compassion.

Then, as if tracking my thoughts, he raised his palm in a gesture of reassurance, and with an encouraging smile, said, “Reb Yehuda, let me tell you what I try to do. Imagine you’re looking at a candle. What you are really seeing is a mere lump of wax with a thread down its middle. So when do the thread and wax become a candle? Or, in other words, when do they fulfill the purpose for which they were created? When you put a flame to the thread, then the wax and the thread become a candle.”

Then his voice flowed into the rhythmic cadence of the Talmud scholar poring over his text, so that what he said next came out as a chant:

“The wax is the body and the wick is the soul. Bring the flame of Torah to the soul, then the body will fulfill the purpose for which it was created. And that, Reb Yehuda, is what I try to do

–

to ignite the soul of every Jew and Jewess with the fire of Torah, with the passion of our tradition, and with the sanctity of our heritage, so that each individual will fulfill the real purpose for which he or she was created.”

A buzzer had been sounding periodically, indicating that others from around the world were awaiting their turns for an audience. When I rose to bid my farewells, the Rebbe escorted me to the door, and there I asked him, “Has the Rebbe lit my candle?”

“No,” he said, clasping my hand. “I have given you the match. Only you can light your own candle.”

I all but trembled as I left his presence.

Prime Minister Begin’s own New York itinerary prior to his departure for home was intense. He called on the secretary-general of the United Nations, briefed editors and columnists, met with academics and business leaders, attended synagogue on Tisha b’Av eve, where he sat in bereavement on the floor and listened to Jeremiah’s lamentations over the destruction of ancient Jerusalem, and on the day after appeared on NBC’s Meet the Press, where Bill Monroe of NBC News kicked off by asking him, “Tell us, Mr. Prime Minister, how did your talks with President Carter go?”

“Before I respond to this very important question,” answered Begin, “I would like to say a few words about this day on which we meet, because of its universal importance. Today, in accordance with our Jewish calendar, is the ninth day of the month of Av. It is the day when, one thousand, nine hundred and seven years ago, Roman legions

–

the Fifth and the Twelfth Legions

–

launched their ultimate onslaught on the Temple Mount, set the Temple ablaze, and destroyed Jerusalem, subjugating our people and conquering our land. Historically, this was the beginning of all the suffering of our people, who were dispersed, humiliated, and ultimately, a generation ago, almost physically wiped out. We forever remember this day, which we call Tisha b’Av, and now we have the responsibility to make sure that never again will our independence be destroyed, and never again will the Jew become homeless and defenseless. This, in truth, is the crux of the problem we face in the future

–

making sure it will never ever happen again. And that, in a nutshell, was the underlying theme of my talks with President Carter.”

66

Other than this extraordinary introduction, the essence of the prime minister’s message was the same wherever he went: Israel’s new peacemaking strategy, with its concrete goal of concluding peace treaties within the framework of a Geneva conference, has led to a newfound understanding between Israel and the president of the United States.

At a packed Jewish assembly in Manhattan, Begin delivered an inspirational address that had people who had thought him a warmonger rise to their feet, enraptured. “Proud Jews of America,” he exhorted them, “lift up your voices high, so that all the world may hear you and be witness to our everlasting Jewish camaraderie, our unity, our eternal sisterhood and brotherhood, in solidarity with Zion, forever.”

Finally, to the sound of summer thunder on the night of 24 July, the El Al jumbo jet carrying the premier and his party home growled off the Kennedy runway, racing across rooftops, trees and lakes, banking sharply over the broad sound of Long Island, until, finally, it settled into a steady drone homeward. The prime minister unfastened his safety belt, helped his wife take off her shoes, and beckoned me over. He wanted to dispatch a farewell message to the president from the plane. “Use this to write on. It won’t be a long message,” he said.

He handed me the flight menu and I, down on one knee, leaned the menu on the prime minister’s armrest, and with Yechiel, Freuka and Patir bending over me like spectators at a chess match, I scribbled Begin’s message exactly as he dictated it. Clearly, his perfumed rhetoric was calculated to dispel whatever odors of Rabin’s March meeting that still lingered in the Oval Office. And since he wanted the captain to dispatch his message right away, I had no time to ‘shakespearize’ it. So this is how it read:

Dear Mr. President,

On leaving the airspace of the United States en route home to Jerusalem may I, on behalf of my wife, my colleagues and myself, express our deepest gratitude to you and to Mrs. Carter, and to your close associates, for the wonderful hospitality you bestowed upon us during our stay in your country. Mr. President, great days in my time have been few. We’ve lived through horrible atrocities. We fought and suffered and mourned. May I tell you that the Washington days were some of the best of my life. They will never be forgotten, thanks to you and to your gracious attitude. I remember well our personal agreements, always to speak and write with candor, to strive for a complete understanding, and that even if there are differences of opinion they shall never cause a rift between us and between our nations. I go back home with the deep hope we are making progress toward peace in goodwill and good faith. Much depends on the other side. Let us hope they will not reject the hand we extend to them wholeheartedly.

Prime Minister Begin helping his wife Aliza with her shoes, July 1977

Photograph credit: David Rubinger & Yediot Achronot Archive

Photograph credit: Ya’acov Sa’ar & Israel Government Press Office