The Railway (28 page)

Authors: Hamid Ismailov

Tags: #FICTION / Literary, #FIC019000, #FICTION / Cultural Heritage, #FIC051000, #FICTION / Historical, #FIC014000, #Central Asia, Uzbekistan, Russia, Islam

Once again, I don't know whether I told the truth about that night. No, no, I don't mean the truth about the events themselves â everything happened as described in these pages; what I mean is â the truth about who was responsible. The easiest thing is to blame it all on Uchmah; but it has also been suggested that the ageing Oppok-Lovely was driven to extreme measures by her longing for her errant husband; there have been attempts to implicate Nakhshon; and there have been mentions of Musayev and God knows who else. Mefody-Jurisprudence â who had by then been deprived of his sinecure, so that Kun-Okhun had had to go back to peeing on his head outside the station instead of in the apple-orchard behind Oppok-Lovely's house â came out with all kinds of nonsense about the triune nature of Hoomer, Shapik and I forget who else; but people with more sense were quick to relate this to Mefody's deep-rooted and profoundly Russian belief that a bottle of vodka should always be shared between three, a belief which, since the death of Timurkhan, had been elevated, in the lawyer's alcohol-pickled mind, to the status of an article of faith. But no one, no one in Gilas thought about the role of the eldest son of Fatkhulla-Frontline â the war veteran who was the mind, conscience and honour of the

mahallya

; no one considered a drawing teacher and retired engineer by the name of Rizo-Zero.

Rizo had been born during the War, after the shell-shocked and half-blinded Fatkhulla had been sent back to Gilas in order to mobilise the women to shock labour on behalf of the war effort. This had led to the three-eyed Rizo, later to be known as Rizo-Zero, being born to the beautiful though small-eyed Zebi. I say three-eyed because above the bridge of his nose lay a small pit the size of an almond that looked like a miraculous third eye.

Making the most of his rights as a war veteran, Fatkhulla sent his son off to the railway institute at the age of seventeen, expecting him to return to his native Gilas as one of Kaganovich's esteemed engineers â but Rizo concerned himself at the institute with matters very different indeed. No, no, not the ones you're thinking of â he didn't drink, he didn't smoke, he didn't seduce women; what he devoted himself to, God knows why, was not the theory of railway construction on loess soil or on sand, but the theory of shadow.

Not only did he read, and write summaries of, everything he could find on this subject in any of the libraries â he also used to sit in the sun for whole Sundays on end, studying the slightest variations in his own shadow on the roof, by the lake, in the student hostel or in the stadium. Any student whose coursework or diploma dissertation touched however tangentially on this problem would find their way to him through an improbable number of intermediaries, and he would gladly compose an essay on “Shadow in Dostoevsky's Petersburg Novels” for an evening-class student of printing or “The Shadow of Gogol in the Work of Bulgakov” for a girl who had undertaken a correspondence course in the Humanities. His generosity, however, bore fruit that for the main part proved bitter: the printer's essay was rewarded with a diploma he did not wish to receive, and the correspondence-course student was all but forced to embark on a doctorate. She was courted by three different supervisors, each trying to win her for their department and thus wrest her away from the regular festive rations to which she was entitled by virtue of her position as technical secretary to some Party committee or other.

But Rizo-Zero did not rest on his laurels. He progressed ever further. When he returned to Gilas with a rather mediocre diploma, the best his father could do for him was to find him a job as assistant to Master-Railwayman Belkov. But by then Rizo-Zero had already learned to annihilate his own shadow. Just before sunset on a summer's day, while old Alyaapsindu was dragging behind him a shadow as long as his long years, Rizo-Zero was able â by means of some system of mirrors, or through the properties of mysterious objects, or because he had acquired the ability to emit an invisible light through his third eye â to walk behind him down the very same sidestreets with only the tiniest spots of shadow beneath the soles of his feet, as if it were high noon.

After an argument with Ilyusha the Korean (usually known as Ilyusha-Oneandahalf because Rizo's donkey had long ago bitten off half of one of his ears) Rizo annihilated Alyaapsindu's shadow as well. The old Korean never again went out of his house; instead he went out of his mind, was overwhelmed by

toskÃ

and died.

It was around then that Rizo-Zero was fired by Master-Railwayman Belkov. He found himself a job as a drawing teacher and appeared to lose all interest in shadows.

It was not long, however, before people began seeing Rizo-Zero up on the roof at night with a telescope; and then, during a drinking bout, Ilyusha-Oneandahalf informed the whole of Gilas that Rizo had taken up the study of stars and was especially interested in solar and lunar eclipses. Ilyusha even tried to intimidate Zukhur, who was refusing to sell him vodka, by threatening that Rizo would bring down a terrible eclipse on the town.

Zukhur went straight to the

mahallya

committee to report this to Fatkhulla-Frontline. Fatkhulla tried to calm Zukhur, as if his power extended not only over his son but also over any eclipses his son might call down. Nevertheless, Fatkhulla thought it better to be safe than sorry; on returning from the chaikhana that evening, he took Rizo aside and approached the subject obliquely: “Your mother and I are ageing, my son. Yes, the old folk of Gilas are quietly dying out. Hoomer, Umarali-Moneybags and now Alyaaps⦔

“But that's not because of

me

,” Rizo-Zero interrupted anxiously. “

I'm

not to blame.”

“Of course not. But there's something else. I've heard you've taken it into your head to call down an eclipse. Please don't â why upset people? Especially when Zukhur's just received a consignment of Russian potatoes. He's promised us a whole sack.”

“Father, what on earth are you saying? Have you no fear of Allah? Are such things in the power of a mere mortal? Not a hair will fall from your head unless He so decrees.”

“That's what I'm saying: don't do bad things. If you've got to do something, do something good.”

And Fatkhulla explained what he and his Ukrainian comrade Petro had done in the War to get German prisoners to talk. Rizo-Zero heard him out, holding in his hand a potato that Zukhur had given his father. Only when his father had finished did Rizo, wanting to show at least some loyalty to science, start to demonstrate what brings about an eclipse; the lamp stood for the sun, his father's face was the earth, and Zukhur's potato â the moon. Rizo-Zero circled the moon round his father's face and, at the very moment when its shadow fell on Fatkhulla's one eye, they heard loud shouts from outside, from somewhere around Oppok-Lovely's house. Other shadows leaped and coiled their way into the house and began creeping across the wall. Fatkhulla grabbed his soldier's belt, from which there always hung a crooked Chust knife, and dashed outside. Rizo-Zero dashed after him. Through the dusty vine they saw the moon shrivelling up before their very eyes, like a scrap of paper caught by a flameâ¦

“I told you not to!” the father shouted, and clipped his son on the ear. The son, still holding the potato-moon, said not a word.

The whole of Gilas was pouring out onto the street. Poor Fatkhulla was so ashamed he didn't know where to look with his single eye.

The following morning, after finding out about the terrible explosion by the canal, Fatkhulla â the mind, conscience and honour of the

mahallya

â cursed every part of his son Rizo from head to toe and threw him out of the house.

Rizo-Zero wandered off down the railway line, examining his thoughts. Thoughts structure themselves according to the path one follows; yes, during his years as assistant to Master-Railwayman Belkov, Rizo had learned to resolve even the most stubborn of contradictions between the two rails beneath him. On this occasion, he was thinking: “I'm walking one step at a time, from sleeper to sleeper. My foot rises, then comes down on the sleeper in front. It settles there. My other foot does the same, with the same movement. What then remains on the sleeper behind? Stop! Let's go through that again. There â my foot is still on the sleeper behind. On the sleeper in front lies only emptiness. And then my foot goes and fills that emptiness, occupying that empty space. But if only a moment ago it was occupying the same form of space on the sleeper behind, doesn't that mean that this emptiness has moved from the sleeper in front to the sleeper behind? It seems then that I move forward, while my empty shadow does precisely the opposite. And if we consider my movement from the level crossing to the wool-washing shed as a whole, then has this emptiness I occupy not carried out the same movement in reverse, from the wool-washing shed to the level crossing? Let me draw a little diagram.” And Rizo-Zero bent down over the sleeper and began, with a sharp stone from the embankment as his stylus, to draw a diagram on the creosoted sleeper:

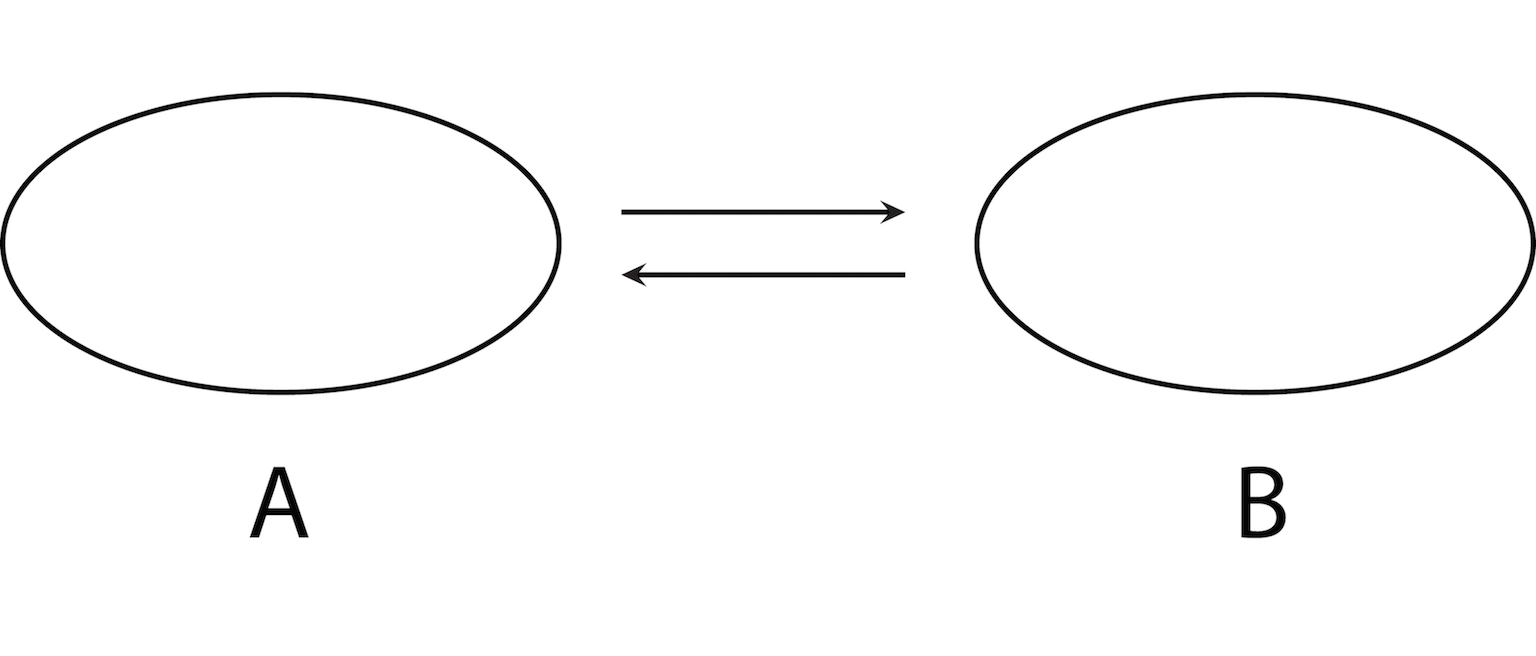

“Here we have the presence, the existence of ellipse A, which is to be transposed, as indicated by the arrow pointing to the right, to its present absence: ellipse B. When it reaches ellipse B, its absence, displaced by its presence, will be transposed to ellipse A; that is A and B will exchange places, but their forms, since nothing in nature can be either destroyed or created, will remain identical during this exchange, that is...” â but before Rizo had pursued his thought to a clear conclusion, there was a piercing whistling, a waving of multicoloured flags and Tadji-Murad, calling Rizo-Zero every name in the book and turning the air blue with his curses, was rushing towards him, closely followed by a wagon he had just uncoupled. Rizo-Zero's thought rushed forward to meet him but, instead of a pure and empty form, it encountered Tadji-Murad's choicest curses: “What the fuck are you doing with your arse stuck up in the air waiting for some fucker to fuck it? Fuck your fucking arse â these wagons will make one great cunt of you! Rizofucking Zerofucker!”

Flabbergasted at the discrepancy between the pure transcendence of thought and the crude language being flung at him, Rizo barely managed to straighten his stiff back before Tadji-Murad, hurtling through space almost as fast as his whistles and curses, slammed into him like one wagon into another and knocked him out of the path of the wagon that had been sent rolling along the gradient.

As they lay there getting their breath back â one from physical exertion, the other from the sudden disarray of his thoughts â Nabi-Onearm, using the freewheeling wagon as cover, jumped across the track with a sack of stolen cotton seeds, tripped over Rizo's large thought-bearing shoe and crashed to the ground, scattering seeds over the railway bed.

“You fuckers!” shouted Nabi-Onearm, seizing the high ground, as he always did, by being first to leap to his feet. His index finger was drilling into the sky, but this time he did not get the chance to speak. Kazakbay-Happytrigger, a guard at the wool-washing shed and the owner of the cows Nabi's seeds were meant to be feeding, suddenly lost his nerve. Afraid that he too might suffer public exposure, he took a potshot at Nabi with his double-barrelled shotgun, cleanly removing the finger with which the one-armed man was pointing at the heavens. Nabi let out a howl and fell to the ground as if dead. Tadji-Murad jumped to his feet to get back to his waving and whistling and inadvertently kicked poor Rizo's forehead with his heavy railwayman's shoe. In the blinding light of this blow, Rizo-Zero saw two rails rushing from one horizon to the other in a vain attempt to meet, suddenly noticed the sleepers that locked them so inseparably apart, and, understanding the meaning of everything in an instant, was thrown into a total eclipse of consciousness.

That summer, cosmonaut Kitov flew into space; when the loudspeaker in the bazaar announced this, the boy's aunts were all in the yard, ironing shirts and trousers for his circumcision. The boy was standing beside them, and he was the only one to hear the voice of all the radio stations of the Soviet Union. He was the first to hear the cosmonaut's surname, Kitov, although the bazaar loudspeaker was interrupted just then by the wheeze of the station loudspeaker, that is, by Ashir-Beanpole wheezing out his eternal, “Attintion, attintion, citizin passingers, thi Sir-DarinskyâDarbazaâChingildi locil train will bi arrivin' it plitform three. It will bi stoppin' fer one minit!”

The boy began to jump about in unaccustomed joy, perhaps because he was proud of understanding what “to fly into space” really meant â unlike the time before, when it had been his aunt Nafisa, throwing her briefcase up into the sky, who had called out, “Lyaganov has flown into space, Lyaganov has flown into space!”

153

That time the boy had felt scared: someone had gone and flown into the sky, with no wings, with no equipment, with nothing at all. Either he'd quarrelled with his wife or else he was wanting to spite someone: he'd just gone and flown up into the sky like Nafisa's briefcase â out of which exercise books, text-books and fountain pens had come raining down.

No, this time it was the boy who had been first to hear the news: “Kitov has flown into space, Kitov has flown into space!” Only the boy had nothing to hurl into the sky; it was the school holidays, and tomorrow would be his circumcision and the yard had been carefully tidied and sprinkled with water.

He felt as happy as if the colt he had been promised a month ago had already been brought into the yard. Tomorrow he would have to sit on the colt and ride round and round the fire till he felt drunk, so that it wouldn't hurt afterwards. He leapt over the patches of sunlight that fell through the thick dusty curtain of the vine and onto the damp, shadowy earth, just as the colt would prance and gallop if it understood what it meant to fly into space. “Kitov has flown into space! Kitov has flown into space!”

Nobody reined the boy back â neither the various “aunties” who lived nearby, nor his granny coming out of the dark house. He knew that tomorrow would be his special day, and so he leapt about until he felt exhausted, until his grandad â or rather step-grandad, since the boy did not have a grandfather of his own, or, for that matter, a father â came in through the gate. Grandad went straight into the dark house, followed by Granny, by Aunt Nafisa and Great-Aunt Asolat and even by Robiya, who was helping them. She was the aunt of Kobil-Melonhead, who was now outside Huvron-Barber's window, playing nuts underneath the cherry trees with Kutr, Hussein, and Sabir and Sabit, the two

lyuli

boys. Kobil-Melonhead, of course, didn't know a thing either about Kitov or about outer space.

The boy longed to go and tell them the news he had been first to hear, but he didn't want to lose his name-day specialness

154

by leaving the house, and so, not quite knowing what to do with himself, he wandered inside after the women, into the dark house, so that he could at least show off about Kitov to Grandad.

But he had barely crossed the threshold before he heard Grandad say in a hopeless tone, “It was a lot of money. I didn't have enough.”

Granny gave a long sigh; one of his aunts began to cry.

Grandad had clearly been talking about the colt. The boy's eyes filled with tears and he stood rooted to the spot. The aunts wandered out of the inner room and stumbled into the boy in the half-dark. They were crying quite openly â goodness knows why â until Granny came and sent them into the yard, saying it was a sin to cry on the eve of a holiday. She didn't see the boy.

All this made the boy angry. He wiped away his tears and went out onto the street, having quite forgotten about Kitov and even about his own specialness.

No, he did not find Kobil outside Huvron-Barber's window â the only boys playing nuts were Kutr and the two

lyuli

boys, Sabir and Sabit. Hussein was sitting on the ground, leaning back against the wall of his house. It was clear that he had already lost and was looking not at the nuts but at the tall figure of Shapik, who was picking his nose beneath the cherry trees.

Old Alyaapsindu was walking down the noon alley, dragging his short shadow behind him. Just as the boy reached the players, Kobil-Melonhead came running up behind the old man, shouting, “Bitov's in space! Bitov's flown into space!” Neither the boy, nor old Alyaapsindu, who went on dragging his shadow along without a backward glance, bothered to point out to Kobil-Melonhead that it was not Bitov but Kitov who had flown into space;

155

nor did the boy feel like saying that it was he who had been first to know, that it was he who had told Kobil's Aunt Robiya. No, the boy no longer wanted anything under the sun.

“And they didn't buy him a horse,” Kobil concluded. Blankly, the boy went up to him and boxed him on the ear. Kobil said nothing, and only Shapik, like a motor gradually gathering speed, began stuttering his “Bloody⦠Bloody fuckâ¦!”

The players were distracted for a moment, even though the game was nearly over. And then, instead of either winning the last nut or losing everything he had already won, little Sabir just grabbed the nut and ran off with it, shouting out, “Quick, Sabit, scarper!”

Sabit had longer legs than Sabir and he dashed after his younger brother, but Kutr managed to trip him up. Sabit crashed down on top of Shapik. They started fighting; little Kutr was going for Sabit's balls, but Sabit for some reason went for Shapik, who was completely innocent. And only a shout from Fatkhulla-Frontline put an end to all this. Kutr and Sabit rushed off in different directions, and Kobil and the boy were left on their own in the shade. Musayev walked by in the sun, muttering slogans. Then Kobil-Melonhead suggested they play filmsâ¦

And so the afternoon drew to an end, empty and useless. In the evening Satiboldi-Buildings and everyone from the

mahallya

began to gather in their house to cut carrots for the

plov

and get everything ready for the following day. Nabi-Onearm was one of the first arrivals and, being unable to do anything very useful with only one hand, he naturally began to organise those who came after him. He sat Tadji-Murad, Rizo-Zero and Faiz-Ulla-FAS down to cut carrots, and he sent Kun-Okhun and Timurkhan off to chop wood and break up coal. Tolib-Butcher began cutting up the sheep; Temir-Iul was put in charge of setting out the tables and benches; Fatkhulla-Frontline sent messengers round the

mahallya

so he could get an idea of how many guests would be coming; Garang-Deafmullah checked that everything was in place for the ritual; Tordybay-Medals brought his son Sherzod, who was going to take the place of the boy's colt; and even Ortik-Picture-Reels, after showing one of his Indian films, turned up at midnight for a cup of tea.

The women of the

mahallya

were working away in the inner rooms; only Oppok-Lovely had yet to return from the City, having gone there to invite her idolised but elusive Bahriddin to the feast. A little further down the street, in Aisha's house, Saniya and Uchmah had sewed countless kerchiefs and napkins from calico they had requisitioned from the house of Soli-Stores. “Stolen goods are the strongest!” Aisha declared, finding that Soli's calico was so sturdy that her scissors were growing blunter more quickly than she could dash to and from the little shop of Huvron-Barber, who was himself hard at work sharpening not only her scissors, but also the knives being used to cut carrot and onion, lean meat and fat, potato and pumpkin, melon and watermelon.

In a word, the entire

mahallya

was at work. Even Uncle Monya, the hunchbacked Jew about whom no one knew anything at all, was applying a fresh coat of paint to his gate.

By midnight, Rif the Tatar gravedigger, had dug a splendid fireplace. Over it hung a vast cauldron, big enough to cook the thirty-five kilos of rice that Murzin-Mordovets, accompanied by Zangi-Bobo and Mefody-Jurisprudence, had brought in his car from the Kok-Terek Bazaar. Murzin gave the bottle he had earned to Mefody, since he himself, as he put it, “would soon be back on the road chasing roubles.” Mefody united his immemorial trinity, and soon he, Kun-Okhun and Timurkhan were on their way to the station to perform their eternal ritual.

That night the boy did not sleep. This, for once, was not because of a lack of supervision on the part of the adults, but at their insistence. It was essential to be tired for tomorrow's circumcision, in order to get through it more easily â and there may have been other reasons as well. Many things, after all, were happening that night for the first time: it was the first time that Rokhbar was baking naan bread in Granny's oven; it was the first time that Grandad wasn't making fun of his friends Djebral the Persian from Shiraz and Fatkhulla the Tadjik from Chust, each of whom had only one eye, but on opposite sides of their faces. Instead of knocking their foreheads together, he was observing everything from the shadows with the dignity expected of a master of the house and whispering to his child-messengers, who transmitted his instructions to Nabi-Onearm, who then jabbered away for all he was worthâ¦

But however the boy tried to stay awake and keep an eye on everything â since that was what Granny had told him to do â all the same, towards morning, after eating piping hot naan bread straight from Rokhbar's oven, he sat down where Grandad used to store huge black watermelons during the winter and curled up for a moment on the cotton hulls. He could hardly have slept long â probably it was no more than the tiniest scrap of sleep â but while he was asleep he saw many things: he was deep in a palm forest, with no sky to be seen at all, and he happened upon a tree stump swarming with wasps â and then from behind this stump appears Rokhbar, who turns out to be Nabi-Onearm, who is sucking his one hand, which has been dipped in either pain or honey. “I'm the beekeeper,” Granny says to Oppok-Lovely, who for some reason has lost not her hand but her leg. “Let's dip your willy in this.” The boy feels frightened, sees Shapik weeping and Sabir and Sabit laughing, then hears the words, “Come on, try these on⦔ When his amputated willy turns in his hands to a pen, he thinks sadly about the colt that was meant to save him, but all he can see by the tethering post is a ladder⦠and then he sees the very same ladder in Rokhbar's oven shed and he hears Granny's very real voice: “Come on, try these boots on⦔

The boy sat on the bottom step of the ladder and, only then remembering his dream, began to try on the new boots.

“They're not too small, are they?”

“What good is it to me that the world is so big if my boots are too small?”

156

the boy said in a voice hoarse from lack of sleep. The women burst into laughter, and Rokhbar slapped her baker's glove against her thigh as she said, “A real little young warrior!”

He walked off in his new boots, which really were a little tight for feet that had spread out during a barefoot summer, but they were gently and snugly tight, as if long barefootedness had made his feet grow a protective sheath. As he walked out of the gate, they made a knocking sound against the five-kopek piece cemented into the ground for good fortune; it was as if his feet were pure bone.

It was already dawn, a quick summer's dawn. Izaly-Jew's cocks woke Lyuli-Ibodullo-Mahsum's donkey, and Lyuli-Ibodullo-Mahsum's donkey woke the cows on the Samarasi Collective Farm. The old war veteran Fatkhulla-Frontline excused himself for half an hour and drove his veteran sheep to the scrubland by the Salty Canal. Last of all, the Koreans' pigs started grunting; their smell, which had ripened during the night, was carried by the dawn breeze towards the station, where Akmolin was hooting and a sleepy Tadji-Murad was frightening equally sleepy crows with his whistle. And along with the dawn, though the sun was still below the horizon, the guests began to arrive for their

plov

.

The first, on his own, still all wrinkled and curled up from the night cold, was Rakhmon-Kul, one of the sons of Chinali; Garang-Deafmullah welcomed him with a prayer, and the two of them shared a bowl of

plov

. Then came the two drivers â Murzin the Mordovian and Saimulin the Chuvash; they had decided to fill up a little before setting out on their journeys. After that Dolim-Dealer, Oppok-Lovely's heir, brought four men who worked as weighers at the Kok-Terek Bazaar. Next Tadji-Murad, whistle in hand, brought Akmolin, who had left his shunter in the siding opposite the little shop of Yusuf-Cobbler; then Yusuf-Cobbler himself wandered in, wearing his green embroidered Margilan skullcap in honour of the

plov

he was about to eat and bowing to all sides to be sure not to miss anyone. Then came: Huvron-Barber; everyone from the cotton factory; the Tatars from the wool factory; eleven Korean footballers about to set out for a friendly match against their fellow-countrymen at the “Political Section” collective farm; and Lyuli-Ibadullo-Mahsum. Next, holding his hand just below his heart in Uzbek fashion, came Master-Railwayman Belkov. Garang-Deafmullah was no longer able to keep up with saying a prayer to welcome each guest, and so Fatkhulla-Frontline â who had returned from taking his sheep to pasture â and Nabi-Onearm â waving his one hand Shiite-style

157

as he greeted Ezrael, the son of the Persian Huvron-Barber â had to help him out, saying prayers of welcome in separate corners of the room. After being welcomed, each guest was served

plov

; they ate decorously, drank a lazy cup of green tea, listened to another prayer from either Tolib-Butcher or Kun-Okhun â who had sobered up after performing his nocturnal duty towards Mefody-Jurisprudence â and then got to their feet and set off to work.