The Road to Woodstock (30 page)

Read The Road to Woodstock Online

Authors: Michael Lang

The Who

© HENRY DILTZ

August 17

© HENRY DILTZ

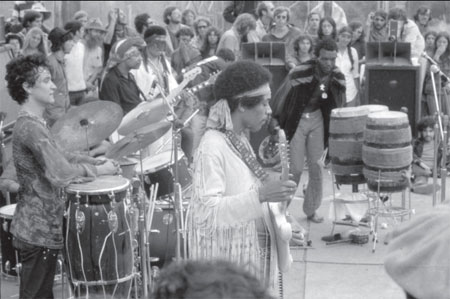

Geraldo Velez and Juma Sultan on percussion, Larry Lee on rhythm guitar, and Billy Cox on bass with Jimi Hendrix

© HENRY DILTZ

Max and Miriam survey the festival site

© BILL EPPRIDGE

T

he morning had started under sunny skies. People woke to the sound of Hugh Romney’s hoarse voice: “

What we have in mind is breakfast in bed for four hundred thousand!

Now it’s gonna be good food and we’re going to get it to you. We’re all feedin’ each other.”

Stan and Hugh had worked out a plan to distribute thousands of cups of granola to the stage area. Some people who didn’t want to lose their spots had not been eating.

STAN GOLDSTEIN:

There were people sitting right in front of the stage dead center who wouldn’t give up their piece of ground to get a sandwich, to have a vegetable, to go to the toilet. They were there and they weren’t moving. Now, if a reporter walked up to them and said, “How are you doing?” “Oh, man, I’m doing all right.” “How long have you been here?” “Oh, I’ve been here for two days, I guess.” “Have you gone off and gotten some food?” “Oh no, man, I’m really, really hungry.” “You haven’t eaten anything in two days?” “No, man, I haven’t eaten anything, I’m really hungry.” And then the reporter goes away and reports that these kids are starving in front of the stage. The fact is, you couldn’t have moved that kid ten feet to get some food.

The Hog Farmers loaded an open-bed truck with garbage cans lined with plastic and filled with granola. Once ready, they guided the truck through the crowd. “

Excuse me, please, truck coming through—please, would you move to the side of the road, we’re bringing a truck through with food

?”

STAN GOLDSTEIN:

I talked to the concessionaires who were out of food and got them to help us load all their unused paper goods to

take to the free kitchen. I got another 150,000 or so potential servings’ worth of paper goods as a donation from the concessionaires.

There were two fewer Food for Love stands on Sunday than there had been the day before. Angry kids and members of the Motherfuckers, fed up by the prices and the wait, burned them down Saturday night. The Hog Farmers tried to defuse the situation and at least controlled the blaze to just the two. Hugh even enlisted help from the kids when he spoke Sunday morning: “There’s a guy up there—some hamburger guy—that had his stand burned down last night. But he’s still got a little stuff left, and for you people that still believe capitalism isn’t that weird, you might help him out and buy a couple hamburgers.”

By Sunday, Woodstock now seemed like a way of life. I was almost used to it—expecting to see the things I was seeing; even the faces in the crowd became familiar. Kind of like seeing people in the neighborhood where you grew up. I guess your mind adapts to anything after a while.

Everybody had settled in, and we’d figured out how to cope with the most pressing problems, and crises like food shortages and sanitation were nearly in hand. We’d gotten into a routine of sending people out to fix the pipes to keep the water flowing—and figured out how to get trucks in and out when necessary.

To start the day’s activities, someone onstage played an out-of-tune “Reveille” on the bugle. The highlight of the morning was the appearance of Max Yasgur. I’d been over to his house a few times through the weekend and Max was having a tough time, enduring several angina attacks. When Mel and I saw him approaching us backstage, we

thought, “Uh-oh, problem.” But as soon as we saw the broad smile flash across his gaunt face, we knew all was well.

MIRIAM YASGUR:

He went over to see what was happening. He wanted to express his thanks and let them know he appreciated the way they were acting. Max came back and said, “You really can’t believe what it looks like from up there!”

I asked Max to come onstage and say a few words to the audience, that they’d love to meet the man who gave them and us his land for this wonderful weekend. He seemed a bit shy about it at first, but it didn’t take long to talk him into it. Chip escorted him up to the microphone and Max began: “I’m a farmer…,” and the people cheered. “I don’t know how to speak to twenty people at one time, let alone a crowd like this.” Max went on clearly and slowly, peering through his glasses at the multitudes stretching as far as the eye could see. “This is the largest group of people ever assembled in one place, but I think you people have proven something to the world: that a half a million kids can get together and have three days of fun and music—and have nothing

but

fun and music! And I God bless you for it!”

It was incredibly moving to see Max up there, overcome with emotion. Watching him address this historic gathering, I was again humbled by the miraculous course of events that had brought us to this moment.

Max was with us all the way. When he found out that a few people were selling tap water to festivalgoers, he hung a huge sign on his barn that said

FREE WATER

. He gave away water, milk, cheese, and butter—and asked a relative to donate bread to go with it. His daughter, a nurse, volunteered in the medical tent, and his son, Sam, helped direct traffic. “If the generation gap is to be closed,” he told a reporter, “the older people have to do more than we’ve done.”

It was time to start the music, and around 2

P.M.

, Joe Cocker went on. Another unknown was about to become a star. Backed by the Grease Band, he stunned the audience with his soulful vocals—and his unique stage moves. I guess you could say Joe kind of invented air guitar that day—or at least popularized it. The Grease Band had a loose approach and opened their set with a blues jam without Joe before launching into their repertoire when Cocker hit the stage. Joe took all kinds of covers and made them his own: “Dear Landlord,” “Feelin’ Alright,” “Just Like a Woman,” “I Don’t Need No Doctor,” “I Shall Be Released.” He turned Ashford and Simpson’s “Let’s Go Get Stoned” into an anthem, ad-libbing a bit about his stay in New York. For the finale, he did what became his signature, “With a Little Help from My Friends.” That song perfectly described the weekend and everybody knew it. His howling, expressive take transformed the Beatles hit into a Joe Cocker song. Just as they were finishing, the sky darkened. Then all hell began to break loose.

JOE COCKER:

I was the only guy in the band that didn’t drop acid that day and I regretted [it] to some degree…I didn’t feel that for this mass of people I was getting through until we did “Let’s Go Get Stoned,” which got all of them up because most of them

were

. When we got into “With a Little Help from My Friends,” I felt as we got toward the end of that tune that we’d caught the massive consciousness. I suddenly felt I’d got them to accept what we were doing. It was a powerful feeling for me. And then it was shattered when somebody yelled to me, “Joe, look over your shoulder!” I looked and saw massive clouds coming in. I just thought, Oh dear, had we done this?

Twenty minutes after we cut power, the worst of the storm passed. But rain continued to fall and we had to keep the concert shut down. I’d planned a surprise for the audience, and as Artie and I stood on

stage watching a plane fly overhead, thousands of flowers cascaded from the sky.

BILL WARD:

It was still cloudy and dark but it had stopped raining, and a little airplane flew over and flowers came floating down. Thousands of people stood there and looked up at the sky. They were just standing there with their mouths open. They were all wet, the place was full of mud, and they were entertaining themselves by sliding in the mud. There was a hilly pasture there, and some people had clothes on and some didn’t, and they’d get a running start and flop down on their butts and slide along in the mud.

GREIL MARCUS:

The kids yelled, “Fuck the rain, fuck the rain,” but it was really just another chance for a new kind of fun. Odd gifts of the elements, our own latter-day saints appeared out of nowhere. In front of the bandstand a black boy and a white boy took off their clothes and danced in the mud and the rain, round and round, in a circle that grew larger as more joined them.

Moonfire, a kindly warlock, preached to a small crowd that gathered under the stage for shelter. A tall man with red-brown hair and shining eyes, barefoot and naked under his robes, he had traveled to the festival with his lover, a sheep…Off in the corner was his staff, topped by a human skull, the pole bearing his message:

DON’T EAT ANIMALS/LOVE THEM

…Albert Grossman, his pigtail soaking wet, was standing nearby and Moonfire ambled over to lay on his blessing. Grossman dug it. Rain simply meant it was a good time to meet new people.

Ten Years After had arrived in the wee hours that morning and were due to go on after Joe Cocker, who they knew from back home in England. The stage was still wet and I was prepared to put the show

on hold until it was safe to repower. But Country Joe and the Fish insisted they could play without electricity. The storm had really put us behind schedule, and there was so much water onstage that we needed more time to clear it. The stagehands tried to discourage the band, saying it was still too dangerous to turn on the power and set up the microphones and amps. But Joe McDonald and Barry Melton wouldn’t take no for an answer. They didn’t need power, they said, they’d play acoustically, with no mics, no amps, no electricity. They had a ukulele, percussion instruments, and some drums.

JOYCE MITCHELL:

Country Joe came in, and he said, “I’ve had enough of this. Those kids are out in the rain, they’re out in the mud. We’re playing music for them.” And that’s what they did. To me, he was a big hero. I can’t tell you how impressed I was with the way he did that.

COUNTRY JOE M

c

DONALD:

When the electricity went out, the kids were bored. Having played a lot of demonstrations, we knew that people would respond to some kind of nonamplified noisemaking. We wound up banging pots and pans and did a little agitprop drumming. We chanted “No rain” and played cowbells, and the audience picked it up. Then we got the idea to pass out drinks to the audience. And everything was going really well until Barry Melton, who was the lead guitar player of the Fish, brought two cases of beer in aluminum cans and started throwing them into the audience and hitting people in the head. Then they started throwing things back at us.

GREIL MARCUS:

The Fish kept on playing and Joe kept on smiling. They reminded me of the brave rodeo clowns that run into the pit when a rider’s hurt and the bull’s ready to trample him.

COUNTRY JOE M

c

DONALD:

I felt completely at home, it was really an amazing free space. In 1969 the counterculture was not a secure place to be. A lot of people didn’t like you and would just come up and hit you or arrest you for being a rocker or a hippie. So it was very refreshing to be in a totally free environment where you weren’t going to be trashed for being part of the counterculture. And it became very obvious to me from the word go that this was our turf.

Along with cans of beer, Barry and the band tossed out oranges and bottles of champagne. Finally, at six thirty, the sun actually came back out and we restored power. Some people had left, but those who stayed seemed almost reinvigorated by the storm. Plugged in, the Fish launched into their regular set, reprising their upbeat “Rock and Soul Music.” By the time they finished, it was dusk. Ten Years After was already onstage, waiting for its equipment to be set up. Their guitarist and singer Alvin Lee was revved up and ready to go.

LEO LYONS OF TEN YEARS AFTER:

We had come from a gig in St. Louis, Missouri, at 6

A.M

. I’d had nothing to eat. I went down to the gig and Pete Townshend came over and said, “Don’t eat or drink anything that’s not in a sealed can because everything is spiked. I ended up on a trip last night, and it’s really, really dodgy stuff.”

We were supposed to go on just after the rain stopped and then Country Joe and the Fish rushed past us and jumped onstage before us. Because we waited so long, we wanted to get on, play, and get the hell out of there. We had tuning problems—we had to stop after the first song and retune, but the audience was great.

Around 8

P.M.

, Alvin Lee opened with the bluesy “Spoonful,” followed by a lengthy “Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl.” The band ended their two-hour set with a long improvisation, “I’m Goin’ Home,” which referenced several early rock and roll songs and showcased Alvin’s

guitar playing. He left the stage lugging a watermelon someone had passed along to him.

Iron Butterfly was booked for Sunday afternoon, but John Morris told me that their agent had called with a last-minute demand for a helicopter to pick them up in New York City. Apparently the agent had a real attitude, and we were up to our eyeballs in problems. So I told John to tell him to forget it, we had more important things to deal with.

LEE DORMAN OF IRON BUTTERFLY:

Two or three times we checked out of our hotel and went to the heliport on Thirty-third Street. But the helicopter never came. I guess it had more important things to do, like feed people. It would have been great to play “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” up there.

Next up was the Band. I was really looking forward to their set. I’d become friends with Rick Danko and Richard Manuel. Though Rick had been hanging out for a while, the others arrived right before the thunderstorm. They seemed a bit overwhelmed, and I think they were nervous about the sound not being perfect. They were very fastidious about their production, and this was going to be pretty loose by their standards. But the festival was down the road from their homes, so this was an easy gig for them.

ROBBIE ROBERTSON:

There was an area where all kinds of people—the artists, managers, record people, whoever—were mingling. Fellini faces were whipping by—it was like a gypsy caravan, a very colorful sight.