The Road to Woodstock (32 page)

Read The Road to Woodstock Online

Authors: Michael Lang

Still, I could not help thinking about what John must be going through. It tore at me that he and Joel had not had the same amazing experience with Woodstock that Artie and I had. For whatever reason, they’d spent a miserable three days stuck in the telephone building in White Lake and now John was having to pledge his trust to pay our bills. I certainly did not have the money to pay my share, and neither did Artie or Joel. I also knew that as bad as John felt, Joel’s position—he was John’s partner but the Roberts family considered him an outsider—was somehow worse.

Joel and John were devastated and turned their anger and resentment toward Artie and me. John’s family was similarly disposed toward us, and even Joel appeared to have become somewhat persona non grata in their eyes. It quickly became them against us. We agreed to table things and reconvene when more information was available.

There was no joy in Mudville that day.

LEE MACKLER BLUMER:

John and Joel came back from the meeting and they were very disturbed. I guess that’s when John’s father said he was going to bail him out. Later he would say they could never use the logo or call anything Woodstock again. John Roberts promised he would never give anybody the license while his father was alive. His father thought it sullied the family’s name. I

think John’s brother finally came around, realizing that it was a cultural phenomenon and that he had so much to do with it. But I don’t think his father ever really forgave John for Woodstock.

I needed to get some sleep before heading back to White Lake to follow up on the situation there. I checked into the Chelsea Hotel and slept for eighteen hours. On my way out, about two o’clock the next day, I saw Janis Joplin, feathers and all, in the lobby. She and her band had been staying there too. “It’s

you

!” she screamed. As I looked around to see who she was yelling at, she jumped all over me.

Public opinion was doing a complete turnaround over the festival. On Tuesday, the

New York Times

published yet another editorial, this time more positive and titled

MORNING AFTER AT BETHEL

. The

Boston Globe

compared Woodstock to the march on Washington, writing:

The Woodstock Music and Art Festival will surely go down in history as a mass event of great and positive significance in the life of the country…That this many young people could assemble so peaceably and with such good humor in a mile-square area…speaks volumes about their dedication to the ideal of respect for the dignity of the individual…In a nation beset with a crescendo of violence, this is a vibrantly hopeful sign. If violence is infectious, so, happily, is nonviolence. The benign character of the young people gathered at Bethel communicated itself to many of their elders, including policemen, and the generation gap was successfully bridged in countless cases. Any event which can do this is touched with greatness.

There was one gap, though, that we weren’t bridging.

Al Aronowitz concluded his daily coverage in the

New York Post

with an article on August 19 titled

AFTERMATH AT BETHEL: GARBAGE & CREDITORS

. In it he asked:

You wonder where the four kids who promoted this thing are going to get the money [to pay off their debts], and Mike Lang smiles and tells you how happy he is. Meanwhile back in New York, his partner, 24-year-old John Roberts, is busy transferring several hundred thousand dollars from one account to another. It was Roberts’ personal fortune that was used to underwrite the venture, with the liability divided four ways. “John,” says Mike Lang, wearing the same Indian leather vest he has worn all week, “is very happy with the success of this thing,” and he tells you how the town and the county and Max Yasgur…have asked the festival to return next year…You ask why you haven’t seen John Roberts all weekend. “Oh,” says Mike, “John didn’t come. He was too nervous.”

On Monday morning, when questioned by Aronowitz, I had been optimistic about the future of Woodstock Ventures. And I didn’t really have a good answer as to why John or Joel couldn’t find thirty minutes to come to the field.

I spent all day Wednesday in White Lake to make sure the cleanup was proceeding and to let the staff know what was up. John had promised that everyone would be paid. I borrowed a pickup truck and drove the fields and back roads to get a sense of the job ahead. It was extensive. We were missing about forty rental vehicles; more than twenty were never found. Some wound up in lakes and ponds.

That evening I headed back to the city. Joel and John had asked

me to come to a meeting at their apartment so the three of us could talk. Before leaving Sullivan County, I thought to stop by the El Monaco and say hello to Elliot Tiber and see how he had made out. We caught up, and as I was leaving, he said, “Wait a minute! I have something for you.” He went to the office and came out with $31,000 in a paper bag. “Here,” he said. “We sold every ticket we had by the morning of the first day.”

All the ticket outlets eventually yielded an additional $600,000. It was indicative of our paralyzed thinking in those first postfestival days that it took Elliot to remind us of the outlets.

I stashed the money under the spare tire in the trunk (actually, under the hood) of my Porsche and took off for the city. I arrived at about eight at their Upper East Side apartment building and parked out front. I was a bit nervous, not knowing quite what to expect. We had all been through a major ordeal together and had been blown apart when it ended. What now? Since the unpleasant meeting at the bank, communication between the four of us had been reduced to zero. When Ripp and Grossman had appeared at the bank that day, I honestly felt repulsed, finding myself cast with strangers against my partners. I thought to myself, “It’s only the specter of John’s family that keeps me on this side of the table.” Artie’s feelings were much less ambivalent. He wanted nothing more to do with John and Joel.

I rang the bell at apartment 32C, and John opened the door looking a decade older than his twenty-four years. Joel looked haggard as well. We sat down and tried to assess things. They wanted to know my plans. I really didn’t have any plans beyond getting through the wrap-up of the festival and dealing with the odd situation our business was in.

John asked if I would be willing to stay with them in Woodstock Ventures, which they assumed they would keep. I had grown to like

and respect John, and although I still had trouble relating to Joel, I thought his heart—if not his head—was in the right place, especially when it came to John. Should I choose to stay on, though, it was clear that Artie would not be with us going forward. While remaining their partner was probably the right move on several levels, abandoning Artie was not something I was prepared to do.

Joel and John were incredulous. They just couldn’t understand my choice. I felt I didn’t have a choice.

As I prepared to leave, I remembered the money I had stashed in the Porsche. “I almost forgot!” I said. “I stopped by the El Monaco and picked up the ticket receipts. After commissions, it came to thirty-one thousand. Would you like me to deposit it, or do you want to come downstairs with me and take—” Before I could finish my sentence, Joel was escorting me to the car.

Over the next several weeks, the four of us began to discuss the dissolution of Woodstock Ventures. It was determined that Woodstock Ventures was $1.4 million in the hole. Joe Vigoda, a music-business lawyer, represented Artie and me. We proceeded on the basis that either they would buy out our shares or we would buy out theirs. My interest was not in getting out of the partnership but in getting Woodstock out of debt. We made an offer that left John and Joel with the debt until we had the money in place to pay them back; John was outraged by this idea. Everyone was screaming at one another—nothing was resolved.

I’d always been pretty good at bringing disparate elements together, but with family pressures and distrust on one side, and the impossibility of a reconciliation with Artie on the other, I could see no way forward together unless we found some immediate relief from our financial problems.

Artie and I went to meet with Freddy Weintraub at Warner Bros. We asked for an advance of $500,000 against our share of the future

profits of the film, so that we could take the corporation out of its immediate problems and pay off some debts. Weintraub said no, claiming that the film’s profitability was in doubt. I thought that was bullshit. Ted Ashley and Warner Bros. execs knew what they had. They were happy to have us in a vulnerable position because that would make their own buyout offer more attractive.

I took the weekend off and flew to England for the Isle of Wight festival, slated for August 29 to 31. I went over with Albert Grossman and the Band, who were backing Dylan. I wanted to see if the spirit of Woodstock had crossed the pond. Should our company survive, this might have some effect on our future plans. The show was a bit of a letdown: As beautiful as the Isle of Wight was, it was missing the magic of Woodstock—at least for me.

Joel saw it this way: “When it was all over, Mike Lang and Artie Kornfeld went off somewhere, to the Isle of Wight, or onto TV shows and said, ‘We’re on to the next thing. Woodstock is history.’ Their two ex-partners stayed there and cleaned up the land and paid the vendors.”

Back in New York, the situation continued to deteriorate. At our next meeting, we sat down to discuss a settlement. This time, we offered to take Joel and John out of the picture by assuming all the debts and paying them $150,000, or they could take us out of debt and pay us $75,000. There must have been some basis for the disparity between those figures, but I no longer remember what it was. We needed an accounting of Woodstock Venture’s financial status so we could present our position to prospective investors. In addition to Albert Grossman, Artie Ripp had found a few other possible backers, and it seemed possible we could raise the money we needed.

Ultimately, as it turned out, Artie and I had to sell our shares to Joel and John. The Roberts clan suddenly changed their tune, threatening the bankruptcy they had been so adamantly opposed to earlier in August, perhaps as a threat. By then I had had enough of the arguments, hassles, and resentments. Our offer to pay off the debts and take over the responsibilities had been sincere. I did not want our employees and vendors to suffer should the Roberts family go through with their threat of filing for bankruptcy. I was not in the Woodstock business, and I never looked at concert promotion as a career path. I had lived out my dream and gained much from its success. If we could not finish this well, I thought, then let’s at least finish it.

So Artie and I agreed to leave the partnership. The split was reported in the

New York Times

on September 8. We relinquished our shares and any right to the Woodstock name. I retained the option to buy back the Tapooz property at cost. Though

Billboard

had run the article describing in detail the new studio to be operated by Woodstock Ventures, the project had languished since things had blown up in Wallkill.

Artie’s and my buyout settlement was a whopping $31,750 each. In fact, our attorney made us sign a letter acknowledging that he was opposed to our accepting the deal.

JOYCE MITCHELL:

I remember going to one meeting at the lawyer’s; I could strangle him now. I didn’t like the fact that they were buying Michael out. I thought that that was wrong—but I don’t think he had a choice.

Shortly after we settled, Warner Bros. paid $1 million to Joel and John to buy out Woodstock Ventures’ half of the film rights, along with a small percentage of the net. Artie and I would never have sold out our

rights, and maybe Weintraub and others at Warners realized that. Artie and I later surmised that talks about a buyout were already in the works with the Roberts clan, unbeknownst to us, before we left Woodstock Ventures.

When

Woodstock

was released in March 1970, it became a tremendous success—and took the festival to people all over America and around the world. It won an Academy Award for best documentary and was nominated for an Oscar in several categories. In the film’s first decade, Warner made over $50 million on it. In 1969, before the movie was released, Warner Bros. Pictures was the least profitable of the eight major Hollywood studios. By buying

Woodstock,

the studio had its first coup in many years. At the premiere, Warner Chairman Steve Ross came up to me and said, “You and Freddy Weintraub can do anything together!” Between the film and a pair of soundtrack albums, Warner’s stock began to soar. The company was in the youth-culture business now. Artie and I never saw a dime from any of the proceeds from the film or soundtracks.

ARTIE KORNFELD:

We probably lost, between us, about fifty million after we were forced out of the company.

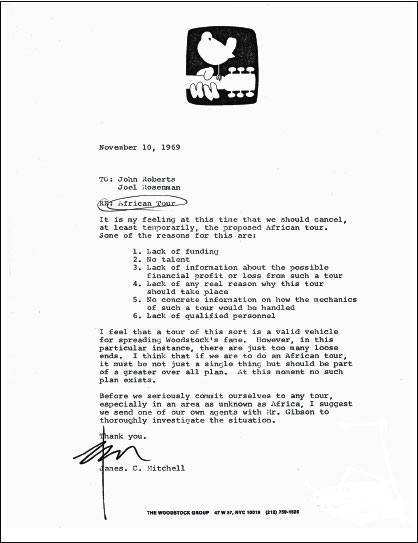

Though we severed our ties with John and Joel, staff members who continued to work for Woodstock Ventures kept me in the loop on things connected to the festival. About six weeks after our split, a copy of a memo to John and Joel from our purchasing agent, Jim Mitchell, crossed my desk. It was in response to a far-fetched business proposition that Joel and John had become taken with: a sort of traveling Woodstock tour throughout the continent of Africa.

I found that pretty funny.

I had moved on, but Woodstock would be with me wherever I went—I didn’t need a package tour for that.

It’s two months after Woodstock, on one of those typically sunny October days in Los Angeles, and I’m driving my rental car down the Sunset Strip. I’d flown out from New York to meet with Columbia Pictures about a film idea.

Rolling Stone,

with the headline

WOODSTOCK

450,000, has hit the newsstands, along with

Life

magazine’s special Woodstock edition. In a few months, the movie and soundtrack album of the festival will be released. I notice the driver of a blue convertible in the lane next to me slowing down and waving. I recognize the sandy hair, long sideburns, and chiseled face. It’s Stephen Stills.

“Hey, man, I can’t believe I ran into you,” he yells. “Follow me over to my house. There’s something you’ve got to hear.”

“Sure,” I say, curious, and I follow him along the busy strip. I haven’t seen Stills since he left Woodstock by helicopter early Monday the eighteenth. We turn right onto Laurel Canyon and drive up the hill until we pull into a driveway tucked behind a security gate. I park next to a Mercedes 600 with the hood up and follow Stills down some steps into a

basement music room, with amps and mics set up. Dallas Taylor is messing around on a drum kit as we walk in, and Stills tells him, “Let’s play Michael the song.” He sits down behind a Hammond B-3 organ, starts to play, and moves close to the mic:

I came upon a child of God

He was walking along the road

And I asked him, Tell me where are you going

And this he told me

He said, I’m going on down to Yasgur’s farm

Gonna join in a rock ’n’ roll band

I’m going to camp out on the land

And get my soul free

We are stardust

We are golden

And we’ve got to get ourselves

Back to the garden…

Stills sees the stunned look on my face, and breaks out into a gap-toothed smile. “Right after we left the festival,” he explains, “we went to see Joni [Mitchell] on the set of

The Dick Cavett Show.

We’d left her behind when we flew up to Bethel—[David] Geffen didn’t think she could get back in time to do the TV spot. She watched the festival coverage on television, wrote this song at Geffen’s apartment in New York, and gave us the tape that night. We just recorded it for our next album.”

I was completely overwhelmed. That feeling of hearing the song for the first time that way has remained with me to this day.

W

ithin weeks after the festival, people began calling with business propositions. I was now in a position to become a national promoter. But booking typical concerts or tours held little appeal for me,

and I didn’t pursue that kind of work. After experiencing Woodstock, I felt most music-business situations seemed mundane. And although I was nearly broke, I was still exploring and trying to understand who I was and where I really wanted to go.

Nevertheless, in December, I got a call from the Rolling Stones organization. Sam Cutler wanted help in the last-minute planning for a concert in northern California. The Stones were losing the Sears Point Raceway days before the free concert scheduled for December 6 and asked if I would fly out to help. It was a disaster in the making, but I agreed to give whatever assistance I could. The Stones and their staff had approached it with good intentions, but with almost no planning or infrastructure. The concert was moved to Altamont Raceway.

That day at Altamont was one of the worst experiences of my life. I truly got to see the dark side of the drug culture. People high on all kinds of exotic concoctions were just wandering through the crowd. There were beatings going on throughout the day, down front near the stage, and there was no one to stop them.

The Hells Angels, who were there to defend the stage and protect their bikes parked next to it, provided the only security. They beat up not only the audience members unlucky enough to have been pushed into their bikes, but also musicians like Marty Balin of the Airplane, who tried to intervene. A member of the audience, Meredith Hunter, was there with his girlfriend and got into a skirmish early in the afternoon. He left and returned later with a gun. When he pulled it out, he was stabbed to death by an Angel. Hunter’s killing was captured on film by the Maysles brothers in their Altamont documentary,

Gimme Shelter

.

Only four months after Woodstock, people were saying that Altamont marked the end of an era. I didn’t see it that way. What happened at Altamont was terrible and showed how awful things can get without foresight and proper preparation. Altamont should have been a great day of music for the Bay Area.

For me, the end came five months later when four students were shot and killed and nine others wounded by National Guardsmen at Kent State University. The image of unarmed American kids being gunned down on a college campus by other American kids in uniform brought home the insanity of how far out of control things had spun during the Nixon administration. Neil Young’s immediate reaction, “Ohio,” which Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young recorded within days, demonstrated again how music could reflect on the events of our time and help to point the way to turn things around.

In 1970, Artie and I formed a partnership and tried to build a new kind of entertainment business together. It didn’t last long. While I loved Artie and Linda, being in business together just did not work. We separated within a year to pursue our own paths. We were such close friends that splitting up the business profoundly affected us personally. Artie felt that I was abandoning him; I felt that I couldn’t stay. It strained our relationship for years.

In the early seventies, after turning down an offer from Gulf + Western execs to run Paramount Records, I agreed to take on a production deal, which then became the label Just Sunshine. I made albums with people whose music I liked: a then-unknown Billy Joel, singer-songwriter Karen Dalton, the R & B vocalist Betty Davis, blues-man Mississippi Fred McDowell, and the gospel group the Voices of East Harlem, to name a few.

Like concert promotion, artist management didn’t appeal to me, but I had managed Billy Joel on an interim basis while we looked for someone to work with him full-time. One day Billy and I were on our way to the airport and “You Are So Beautiful” by Joe Cocker came on the car radio. Billy looked over and said, “You know, no matter how many times they count this guy out, he always seems to get up again.”

I became reacquainted with Joe Cocker in 1976. I knew he had destroyed his career by doing too many disastrous shows too drunk to stand up. Still, I was shocked by his physical condition and near incoherence. Remembering Billy’s words, I agreed to work with him on a temporary basis to try and rebuild his health and his reputation. That association lasted for sixteen years. During that time I helped him to get control of his drinking, refocus on his incredible talent, and reestablish himself as a major star in Europe and around the world. (In a

Spinal Tap

moment in 1991, we would part company.)

While managing the careers of Joe and also Rickie Lee Jones, in 1987 I produced a festival with West German promoter Peter Rieger for 250,000 East German kids behind the wall in East Berlin. With Joe as the headliner, we added bands from East Germany, Russia, and West Germany. We followed that with another outdoor concert for 100,000 kids in Dresden. We were the first Westerners to play Dresden since World War II.

These events were to be the lead-up to a twentieth-anniversary Woodstock event in 1989. I hoped to have it take place on both sides of the Berlin Wall. I thought the spirit of Woodstock could create a bridge between East and West.

After an incredible two years of meetings and dozens of cloak-and-dagger interludes in East Germany, I finally attained tacit approval from the Honecker government to proceed. But in the end, the project was torpedoed by Warner Bros. and the Communist Party in Moscow. Strange bedfellows.

As it happened, on the day the wall fell in 1989, I was back in Berlin on a Cocker tour. With the mayor, we organized a spontaneous concert/celebration featuring bands from the East and the West. With millions of people in the streets of Berlin and more pouring “through” the wall, it was an amazing experience to be in the midst of history being made.

Though for years I would have bet against it, there would be two festivals celebrating Woodstock anniversaries: in 1994, on the twenty-fifth anniversary, and in 1999, for the thirtieth. John Roberts and I had always managed to stay in touch, and in the late eighties we began talking about Woodstock again. Eventually he, Joel, and I met to discuss the twenty-fifth anniversary.

In the winter of 1994, I managed to secure the 800-acre Winston Farm, the Schaller land near Saugerties we’d originally wanted for Woodstock. With three-fourths of Woodstock Ventures reunited, I brought in John Scher, then president of PolyGram, and together we produced what we all felt was a great festival for 350,000 very happy kids and, in many cases, their parents. Artie, whose wife Linda tragically died in 1988, came up from Florida to share the weekend of August 12, 13, and 14 with us.

Many of the original Woodstock performers returned, including Santana, Joe Cocker, and Crosby, Stills and Nash, as well as new artists Sheryl Crow, Green Day (whose manager had been in Sha Na Na in ’69), Porno for Pyros (whose leader Perry Farrell started Lollapalooza, a kind of traveling Woodstock), the Red Hot Chili Peppers, and Metallica. The press criticized our getting corporate sponsorship (Pepsi), but that had become part of the concert business—even for Woodstock. And most people who came could have cared less. The realities of the festival’s costs (over thirty million dollars) meant that the ticket prices for the weekend would have been substantially higher without sponsors. Though it was not my ideal scenario, I was basically okay with it as long as it didn’t compromise our plans.

In true Woodstock style, the communal spirit lived, it rained like hell, Mud People abounded, and Woodstock ’94 made money for everyone but us.

Five years later, on July 23–25, Woodstock ’99 took place at Griffiss Air Force Base in upstate New York’s Mohawk Valley, near Rome. John Scher (now at Ogden), Ossie Killkenny, and I produced the festi

val, with Woodstock Ventures serving as the licensor. We wanted to return to the bucolic Winston Farm, but the political balance of the Saugerties town board had changed and they could not reach a decision on moving forward with us. Griffiss was well suited should it rain, and the logistics there were fantastic: hundreds of buildings to house our crews and staff; hundreds of acres for parking, camping, and performances; and easy access to the site.

I again wanted a mix of classic acts, jam bands, and the less extreme side of the hard-edged music happening at the time. Going against my instincts, I went along with the consensus and so the lineup, an amazing amalgam of the biggest acts of the day, was darker and more aggressive than I would have liked. At one point during planning, I was talking to Prince about a Hendrix tribute, and he asked me, “Why are you having all those nasty bands?” I did not have a good answer. During the performances of acts like Limp Bizkit, Korn, and Rage Against the Machine, the mosh pit was a scary sight. The audience surfing got pretty aggressive, and we were horrified to later find out that incidents of women being molested had been reported.

The weather was brutally hot, with no rain for relief, and while there was plenty of free water on tap, concessions were selling it at $4 a bottle, as though it were Yankee Stadium. When I found out about the prices, I tried to get the concessionaires to reduce them to something sane, but I was told it was too late to change them. To balance this, I ordered several trailerloads of water to be distributed for the taking around the site. While the vast majority of the kids had a good time, the festival became more like a massive MTV spring-break party than a Woodstock.

At 7

P.M.

on the final evening, the mayor of Rome and various county and state officials held a press conference to congratulate us on a terrific weekend and to invite us back. A few hours later, as the festival was ending with the Chili Peppers covering Hendrix’s “Fire”

( which had been so powerful in ’69), some of the kids in the back of the audience began lighting bonfires. Soon a group of about fifty goons, bent on provoking the crowd, decided to torch a line of supply trucks; then they went through the concession stands, “liberating” whatever they could. When the melee grew to involve several hundred people, the police came in en masse. Kids were running everywhere, mostly to get out of the way. I waded out into the middle of it to make sure the cops were not overreacting. And to their credit, they showed great restraint in the mayhem.

In retrospect, I realized I had failed to heed the lesson I had so clearly learned in 1969 and many times since: trust my instincts.

In the years since Woodstock, I have put on many events in America and abroad and have pursued interests in music, film, and the arts. Along the way, I produced a short film by Wes Anderson called

Bottle Rocket

, which introduced Wes and the actors Luke and Owen Wilson to the world. While on a trip to Moscow and working with the Kremlin Museum, I acquired the film rights to the Russian classic

The Master and Margarita

, by Mikhail Bulgakov. It is now in development and projected to shoot in 2010.

In the past forty years, Woodstock has been the elephant in the room in my life. To keep it in perspective, I have made the room much bigger. It is full of family and friends and adventures lived and yet to come.

Many of Woodstock’s artists look back to the festival in ’69 as a turning point for all of us. As Carlos Santana recently said, “At Woodstock I saw a collective adventure representing something that still holds true today. When the Berlin Wall came down, Woodstock was there. When Mandela was liberated, Woodstock was there. When we celebrated the year 2000, Woodstock was there. Woodstock is still every day.”