The Road to Woodstock (28 page)

Read The Road to Woodstock Online

Authors: Michael Lang

ELLEN SANDER:

Janis Joplin danced with them as if they were one, they shouted back at her, they wouldn’t let her off until they’d drained off every drop of her energy.

Everyone was primed for Sly and the Family Stone—who were ready to put on a SHOW. They were decked out in fantastic outfits—Sly in white fringe, Sister Rose in her platinum wig and fringed go-go dress, and bassist Larry Graham in a feathered hat with matching suit. Their performance was beyond phenomenal—“M’Lady,” “Sing a Simple Song,” “You Can Make It If You Try,” “Everyday People.” During the spectacular finale, “Dance to the Music”/“Music Lover”/“I Want to Take You Higher,” Sly took us all to a psychedelic church as he and five hundred thousand people did a feverish call-and-response like a preacher and his congregation in a revival down South.

CARLOS SANTANA:

I got to witness the peak of the festival, which was Sly Stone. I don’t think he ever played that good again—steam was literally coming out of his Afro.

ELLEN SANDER:

Grace Slick and Janis Joplin were dancing together, their eyes tight shut and their fists clenched and their bodies whipping around. “

Higher!

” Sly shouted into the crowd. “

Higher

!” they boomed back with the force of half a million voices at their loudest. He threw up his arms in a peace sign, a billow of fringe unfurled around them, and the audience responded, shouting “Higher” in unison and raising their arms and fingers into the air, joyously, desperately, arms and hands and fingers raised in peace signs, heads and voices crying out into the night, crying the anguished plea of the sixties,

“Higher, higher

!”

It took a while to come down after Sly’s performance, but leave it to Abbie Hoffman to turn the mood around. He grabbed me backstage, saying in a panicked voice, “I just saw someone running around with a gun, you’ve got to help me find him!”

I didn’t realize it at the time, but Abbie, after a twenty-four-hour shift in the medical tents, had decided to take the edge off. He’d popped a hit, or two or three, of acid. Not seeing anyone from security around, he and I went to find the gunman.

“I think he went under the stage

!” Abbie said with total conviction, so we started looking everywhere under the massive structure where assistants were changing film magazines. After a few minutes of futile searching, Abbie stopped. He turned to me with this perplexed look and said, “You really aren’t afraid to die, are you?”

I wasn’t sure what to make of this, but I started to question the wisdom of this quest. When the “nut with a gun” turned into the “nut with a knife,” I realized the only

nut

I was likely to run into down there was Abbie.

It was three thirty in the morning and the Who were about to go on, so I said, “Look, Abbie, whoever you saw is gone, so let’s just go watch some music and chill out for a few minutes.”

He agreed and we headed back up to the stage to sit with musi

cians from various groups who’d gathered to watch. Abbie kept fidgeting next to me. He couldn’t stop talking. “I’ve really gotta say something about John Sinclair! He’s rotting in prison for smoking a joint!” Sinclair, the manager of the radical Detroit rock band the MC5 and the founder of the White Panther Party, was set up by the cops and sentenced to ten years in prison for the possession of two joints.

“Okay, Abbie,” I tried to reason with him, “there will be a chance later on, between sets or something.”

But he persisted. “No, I really gotta say something!

Now!”

“Abbie, the Who is on,” I reminded him—they were about halfway through performing

Tommy

in its entirety, so I don’t know how he failed to notice. “You can’t make a speech in the middle of their set—let them finish!

Chill out!

”

Just after “Pinball Wizard,” Abbie leaped up before I could grab him and rushed to Townshend’s mic, while Pete had his back turned and was adjusting his amp. Abbie started earnestly beseeching the audience to think about John Sinclair, who needed our help. He was in his element, berating everyone for having a good time.

“Hey, all you people out there having fun while John Sinclair is being held a political prisoner…”

WHAM! Townshend, turning back to the audience and seeing Abbie at his mic, whacked him in the head with his guitar.

Abbie stumbled, then jumped to the photographer’s pit, dashed over the fence, and vanished into the crowd below. A pretty dramatic exit. That was the last I saw of him that weekend.

HENRY DILTZ:

I was right in front of the Who, on the lip of the stage. There was Roger Daltrey, with his fringes flying. Abbie Hoffman ran onto the stage and Pete Townshend took his guitar and held it straight out, perfectly, with the neck toward the guy, just like a bayonet, and went

klunk

. I thought he killed him.

Early in the set, Townshend had already kicked Michael Wadleigh in the chest while the director crouched in front of him with his camera. Now Townshend was over the top with fury. “

The next fucking person who walks across this stage is going to get fucking killed!

” he yelled as he retuned his Gibson SG. The audience at first thought he was joking and started laughing and clapping. “You can laugh,” he said coldly, “

but I mean it!

”

PETE TOWNSHEND:

My response was reflexive rather than considered. What Abbie was saying was politically correct in many ways. The people at Woodstock really were a bunch of hypocrites claiming a cosmic revolution simply because they took over a field, broke down some fences, imbibed bad acid, and then tried to run out without paying the bands. All while John Sinclair rotted in jail after a trumped-up drug bust.

The Who continued with their exhilarating performance of

Tommy,

and just as the sun rose, they played raucous rock and roll classics from their days as mods: “Summertime Blues,” “Shakin’ All Over,” and “My Generation.” They were astonishing. Later, I couldn’t believe the band thought they were subpar and that the audience didn’t get into

Tommy

.

PETE TOWNSHEND:

Tommy

wasn’t getting to anyone. By [the end of the set], I was about awake, we were just listening to the music when all of a sudden,

bang

! The fucking sun comes up! It was just incredible. I really felt we didn’t deserve it, in a way. We put out such bad vibes—and as we finished it was daytime. We walked off, got in the car, and went back to the hotel. It was fucking fantastic.

BILL GRAHAM:

The Who were brilliant. Townshend is like a locomo

tive when he gets going. He’s like a naked black stallion. When he starts, look out.

ROGER DALTREY:

We did a two-and-a-half-hour set…It made our career. We were a huge cult band, but Woodstock cemented us to the historical map of rock and roll.

The Jefferson Airplane did their best to follow the Who, but anything after that would have been anticlimactic. The sun was shining, though, and the Airplane, who’d been partying for twenty-four hours, made the most of it. Joining them on keyboards was Nicky Hopkins, who’d played with the Stones and had been slated to play Woodstock with the Jeff Beck Group. “You’ve heard the heavy groups,” Grace Slick said from the stage, “now welcome to Morning Maniac Music.” Grace’s beauty took my breath away. She, Marty Balin, Jorma Kaukonen, and Paul Kantner alternated lead vocals. “Somebody to Love,” “Volunteers,” “White Rabbit”—they did their big hits and also longer, psychedelic jams.

GRACE SLICK:

We’d been up all night and I sang the goddamned songs with my eyes closed, sort of half asleep and half singing. We probably could have played better if we’d been more awake, but part of the charm of rock and roll is that sometimes you’re ragged.

They were exhausted, as were we all. Our newly created city was cast off into some crazy dreams by their trippy morning lullaby.

The perfect way to begin to day three.

AUGUST 17, 1969

It’s four thirty on Sunday, and the first act of the day—Joe Cocker and the Grease Band—have just finished their set. There’s a storm coming and it’s going to be a lollapalooza. I haven’t seen the wind kick up like this since a tropical storm blew through Coconut Grove in 1966. The stage crew is racing around to cover all the equipment with the last of the plastic and tarps before the rains come. After three days of this, we’ve run through miles of plastic sheeting. Booming thunder and jagged streaks of lightning seem to be Nature’s way of saying it can produce fireworks far beyond the sonics blasting from our stage.

Some of the stagehands point to previously buried cables, becoming noticeably more visible as the earth has turned to mud over the past day. These cables carry electrical wire from under the stage to the towers. One of the stage electricians is convinced the cables’ outer shell is wearing away, exposing hot wire. Chip says he’ll check them out but that these “horse dong” cables are impenetrable, that stomping feet

can’t break through the shell. They are mining cables and have a solid copper casing under the outer rubber. But while we are powwowing, someone panics and calls over to the telephone building and gets Wes’s security ally John Fabbri all freaked out. He says we should shut down, and he and Joel argue over which would be worse: a violent riot or mass electrocution. I ask someone to call back and tell them we’ll make sure neither happens. The cables are safe, but the stage power can’t be used during the thunderstorm—we’ll have to shut down for a while anyway.

I’m used to the rain. More troubling are the sixty-foot towers. On top of those towers are the massive Super Trouper lights weighing hundreds of pounds apiece. If one shakes loose, it could be disastrous. The forty-mile-an-hour winds are making the towers sway, which is a frightening sight, especially since kids are perched on the scaffolding—thousands more packed around the towers’ bases. Chip sends some of the riggers to the top of the towers to lay the lights on their sides and tie them down. The towers are engineered to withstand high winds, but this storm is pushing their limits, especially with the kids’ added weight. We’ve got to get people off them and away without causing panic. The wind is fierce—gusts are blowing rain like wet bullets, drenching everything.

John Morris reacts quickly: He grabs the mic to let the audience know what we’re going to do and what they should do. “Please, get down from those towers! Move back away from the towers! Clear away before someone gets hurt! Keep your eyes on those towers.” He stands alone onstage as the crew, musicians, and bystanders seek cover. Though the mic is hot, he has to get the message out before power is cut.

After two days of onstage announcing and not much sleep, John’s voice is shot. I watch him give his all to help keep people safe. He’s holding what could be a lightning rod in his hand, but he doesn’t flinch. “Wrap yourself up, gang—looks like we’ve got to ride this out!” John tells the crowd we have to shut down until the storm passes, but we are here with them and

they are with each other and together we will get through this. It is a heroic moment for John.

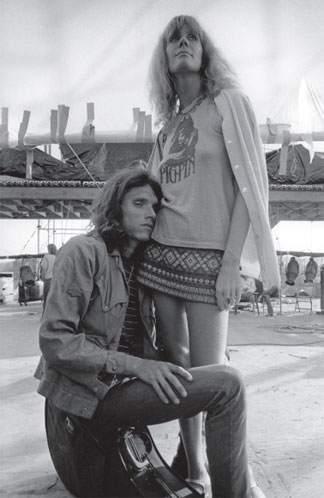

Copping

© BARON WOLMAN

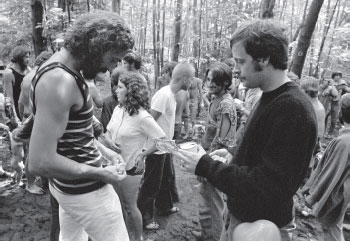

A clothing boutique in the woods

© BARON WOLMAN

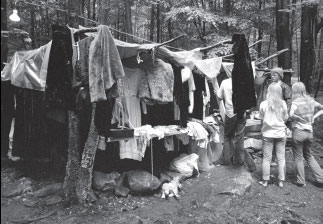

Watermelon stand

© KEN REGAN

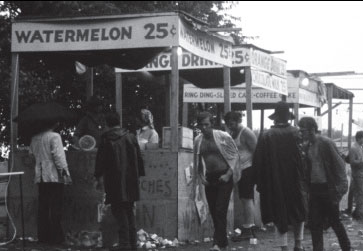

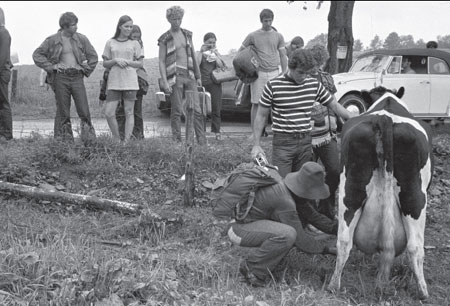

Fresh milk

© BARON WOLMAN

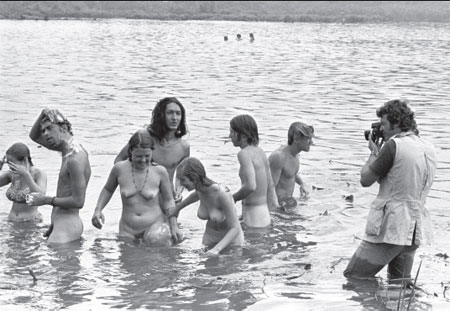

A photographer getting his feet wet

© BARON WOLMAN

© HENRY DILTZ

Penny taking a break at the side stage

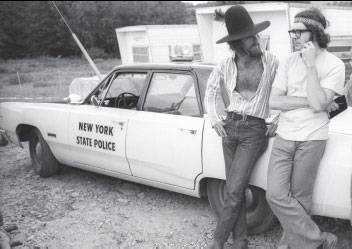

Filmmakers Michael Wadleigh and Bob Maurice

© HENRY DILTZ

© KEN REGAN

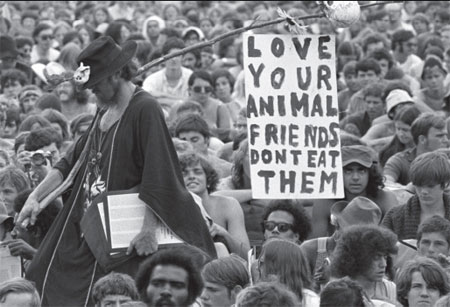

Animal rights at Woodstock

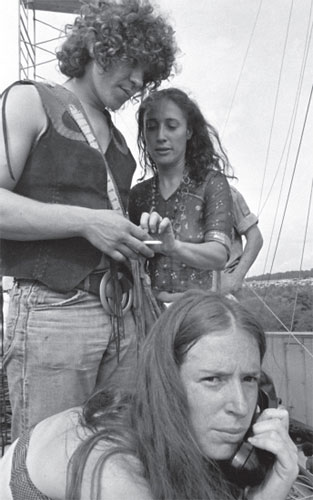

Me with Joyce Mitchell and Ticia on the phone.

© BARON WOLMAN

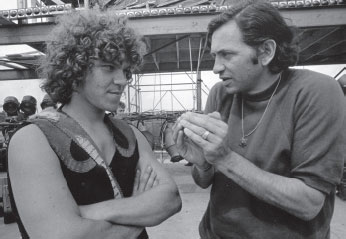

Me and Bill Graham

© JIM MARSHALL

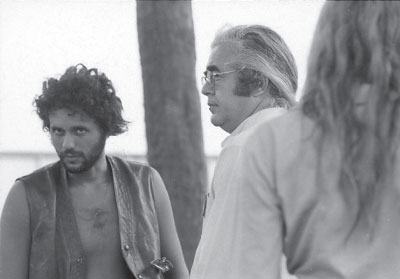

Artie with Albert Grossman

© HENRY DILTZ

Checking on Tim Hardin

© HENRY DILTZ

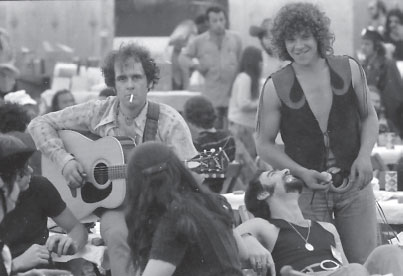

Joan Baez with Joe Cocker’s manager Dee Anthony and Joe’s producer Denny Cordell

© HENRY DILTZ