The Second Wave (2 page)

Authors: Michael Tod

Everything that felt uncomfortable, it seemed, was ‘good for you.’ The bundle of dried grass that he had once brought into the cave to make the ground less hard to sleep one had been thrown out, and he had been called ‘a self-indulgent squimp’. He was

glad

the old squirrel was gone, but now his father seemed to be just as awful!

Crag, Rusty and Chip doggedly worked their way down the cliff-face, one paw searching for a new hold whilst the other three paws held on to whatever projection or crack their sharp claws could cling to. Crag and Chip moved confidently, head down, but Rusty, never happy on high faces, descended slowly, tail first, feeling for holds and keeping her teeth clamped tightly together. It would not do to show fear.

Chip called out to her, ‘There’s a good hold just below your left paw,’ but his words were lost in the splash and roar as the rain squall reached the land, drenching the squirrels on the rock face. In a moment their wet fur flattened to their skins and their tails became as thin as those of rats.

‘Hold on,’ shouted Crag. ‘It’ll pass in a moment.’

They clung on to the rock face chilled and uncomfortable, Rusty’s teeth chattering audibly. Then, as suddenly as it had arrived, the squall passed on and the sun was visible again, though now so low that little warmth reached the cliff-bound animals. Crag signalled them to start down again.

The light was fading from the western sky as the three reached the tumbled rocks piled along the cliff-base. Here there was some protection from the wind, and the bedraggled animals hopped down from rock to rock, making their way towards the shore.

Chip could hear the crashing of the waves above the roar of the wind and a melancholy whistling as the gusts tore through the brambles and the shrubby bushes which grew between the fallen rocks. He shivered and kept close behind his mother, hoping his father would stop soon. He was cold and hungry, and this unfamiliar place frightened him.

As the last of the daylight died they came to a Man-den, a wooden hut built between two great rocks, where his father and mother sniffed the air for recent scents. Then, apparently satisfied, Chip’s father wriggled into the darkness underneath the hut’s wooden floor.

‘This’ll do for us,’ he called back, and Rusty and Chip crawled in after him.

Compared with the outside world, it was warm under the hut floor and the youngster licked himself dry – he could hear his parents doing the same. He was very hungry, but knew better than to ask for food, which plainly wasn’t to be had that night. He would have to wait until morning, so he fumbled about in the darkness for a sleeping place. In a corner he found a pile of dry grass brought in by some other animal, and quietly and guiltily burrowed into it. He knew this was a sinful act, but he was

so

cold. No squirrel would know, but he must remember to be lying on the bare ground before it got light.

He heard his father start the Evening Prayer.

‘Invincible Sun,

Forgive us, your poor squirrels,

For always failing.

Tomorrow, we will,

If you give us the strength,

Try to do better.’

Try to do better at what? Chip wondered. What would the Mainland be like? Would they find other squirrels? Would they be like he was? There were so many questions that he dared not ask. He wriggled round in the grass and slept restlessly.

CHAPTER TWO

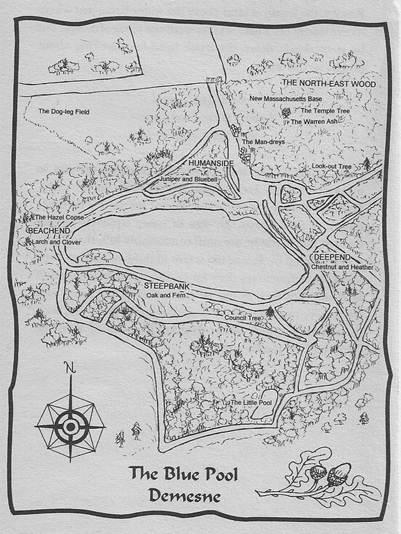

The rain and the wind had died away during the night and the red squirrels at the Blue Pool, on the Mainland fifteen miles to the north-east of Portland’s great rock, peered out of their snug dreys at the pink glow in the sky that was the herald of a warm autumn day.

Alder the Leader had declared this day was to be Sun-day, devoted to fun and recreation.

Even as early as this, the squirrels could sense the squirrelation that would spread from drey to drey and bring them all together to enjoy each other’s company, with feasting, chases through the branches and, in the dusk, story-telling in the Council Tree on the steep bank overlooking the pool.

Each knew that the Harvest was in. Their weeks of frantic activity were over, and sufficient nuts were hidden and buried to see them through the hardest of winters and well into the otherwise hungry days of early spring.

The nuts had been hidden in groups of eight. By their ancient law, embodied as always in a Kernel, they would dig up and eat only seven of these.

One out of eight nuts

Must be left to germinate.

Here grows our future.

Marguerite the Tagger paused with her head outside and her body still in the warmth of the drey high in the Deepend tree. She sniffed the air and pulled her head inside. There was time for another little doze. Her two youngsters, Burdock and Oak, were big enough to fend for themselves. Together with the other squirrels born that year, they had been tagged at her recommendation with an appropriate Tag to indicate their character, or to commemorate some worthy, or unworthy, achievement.

To be a True Tagger demanded a great deal of observation and concentration. An unfair denigratory tag could ruin a squirrel’s life, though there would always be a chance to earn a better one. This year had produced a good-quality harvest of dreylings. One was her own son, Young Oak, who had earned his tag, the Wary, because he was always suspiciously alert for any sense of danger. Marguerite’s own father, Oak, Young Oak’s grandfather, was tagged the Cautious, and some squirrels thought that the two tags meant the same thing, but, to a True Tagger, there was a world of difference. It was a good thing to have a ‘wary’ son – it meant that there was a better chance of grandchildren. Being Wary was a good trait.

Her brother, Rowan the Bold, lived at the humans’ side of the pool. His tag had been with him since he was a dreyling and suited him well, though now as a father of two he could not indulge in exciting climbabout journeys away from the Blue Pool any more. Marguerite was sure that he missed these and that he sometimes fretted at the lack of opportunity to be bold and adventurous.

One of her short-lived uncles, Beech, had earned the tag the Ant Watcher from his obsessive fascination with the way wood-ants carried food to their nests under huge mounds of pine needles. Beech had been on the ground watching a little group foraging when the fox had seen him. The Ant Watcher had not even felt the snap of its jaws.

Marguerite’s daughter, Young Burdock, had been tagged the Thoughtful. Like Marguerite herself, she was always trying to puzzle out complex things. Marguerite recalled her own early tag, the Bright One, and wanting to know exactly to what it referred – but even then she had known that it was bad form to question your tag.

Now, with the two youngsters chattering excitedly on the branch outside, she gave up any hope of a doze and nudged her life-mate, Juniper the Steadfast, to wake him.

It had taken him a long time to earn

that

tag. He was two years her senior, and she had never even known his first tag. It had been the Scavenger when she was a dreyling, then the swimmer after an incident with the invading grey squirrels the year before. Finally, he had earned his present tag by always being reliably at her side through all the dangers and hazards they had experienced together since his first life-mate, Bluebell, had given her life to save others. Bluebell was the only squirrel to have had a tag-change after death; she was awarded the tag Who Gave All to Save Us in place of Who Sold Herself for Peanuts, which had been earned by behaviour they all wanted to forget.

Marguerite wriggled out of the drey, sat on a branch and groomed herself in the sunshine, licking her fur and combing her tail-hairs with her claws. Soon Juniper followed her.

‘Perfect day for a Sun-day,’ he said, looking round at the tops of the pine trees where the rain-soaked needles were steaming away the night’s moisture, then down to the pool, which he could glimpse through the tree-trunks below. He sat there, as he did on most fine mornings, combing his whiskers and enjoying the colour of the pool. It was a different colour every day. Sometimes, as now, it would be blue. On other mornings it would start green and change through several shades to turquoise and eau-de-nil. Even on overcast days it usually ended up that intense sapphire colour that had earned it the Blue tag and which attracted humans to come and see it summer after summer.

Marguerite and her family climbed head first down the trunk of their tree to forage, pausing below branch level to look about and scent for possible danger. Juniper spoke the Kernel –

‘A watchful squirrel

Survives to breed and father –

More watchful squirrels.’

Kernels as important as this one could not be repeated too often. Knowing these Kernels of Truth gave the youngsters the greatest chance of survival in a world in which a squirrel would be regarded by many animals as nothing more than a welcome meal.

It is so peaceful here, now that the Greys have gone, Marguerite was thinking. So pleasant to live quietly in this beautiful place with her life-mate and their youngsters after the frenetic action of the previous two years. And yet … No, she didn’t really enjoy all that activity, and yet … She had to admit to herself that it was exciting having to plan for your very survival, using your wits, and your energy and skills, to keep one leap ahead of your enemies…

CHAPTER THREE

Chip woke with a start. It was still dark, but he knew he must be out of the warmth of the dried grass before his parents discovered that he had sinned by indulging himself with comfort. He thought there was a little time yet before his parents would wake, so he wriggled down again into the warm nest. The storm must have blown itself out. There was no wind-sound, though he could feel vibrations through the ground from the sea-swell pounding the rocky shoreline.

He lay there, listening to the breathing of his sleeping parents, trying to identify an unfamiliar feeling that surrounded him. He tried to focus on it, straining his mind and his whiskers to pick up whatever it was. In a way it resembled the warmth of the grass around his body, but it was more subtle than that. It came from the wood above him, from the Man-den, the hut on its little plateau amongst the huge boulders.

There were no men there – he would have scented and heard them moving long before this – but it

was

Man-associated. It was something like the ‘cared for’ feeling he remembered from his mother when she has suckled him back in the spring. Then, in a distant, painful memory, he recalled his grandfather, Old Sarsen, saying, ‘Don’t get squimpish about that youngster. He’s not yours. You have only borne him to serve the Sun.’ And over the next few days that warm, cared-for feeling had been withdrawn.

Now he sensed that the hut was cared for – by humans. Could

things

be cared for? Could squirrels themselves ever be cared for except when they were dreylings? He hugged himself with the excitement of the thought.

A finger of grey light probed under the hut. Chip quietly destroyed his nest in the corner and moved away from the scattered grass to lie down on the cold soil until his parents woke. They lay as they taught him to, with their tails away from their bodies so as not to indulge in the warmth these might unworthily give them. He copied them and shivered.

A herring-gull, perched on the ridge of the hut above, called raucously. Crag and Rusty sat up at the same time and Rusty reached out and shook her son’s shoulder where he lay, pretending to be asleep. ‘Time for prayers, Chip-Son,’ she told him.

Crag glowered at her.

‘Chip, you must wake now,’ she said forcing herself to sound hard and uncaring.

The three went out into the chill of the dawn air. If the sun

was

up over the eastern sea, it was hidden by the vast stone bulk of Portland behind them. Crag climbed on to a small rock, gave a quick look round for danger and, seeing none, said the Morning Prayer –

‘Be not too wrathful,

Oh Great Sun, on those squirrels –

Who sinned in the night’.

Chip shifted uncomfortably as Crag went on.

‘Let us serve your needs

For the whole of this your day

Weak though we may be.’

‘Let us find sustenance,’ Crag said, after the long silence that followed, and only then could they start to forage amongst the rocks for food.

On the seaward side of the hut a spring of clear water trickled down through small pools overhung with brambles. Each drank from the stream in turn – first Crag, then Rusty, then Chip.

They found a few roots and a puffball which, though beginning to set spores, was just edible. These, with a few hard-pipped blackberries and some crimson hips, made up their meagre breakfast. Then Crag saw some sloes on a stunted blackthorn bush between two rocks and allowed each of them one of the mouth-drying fruit, before ordering Rusty and Chip to follow him along a Man-track that wound between the boulders.