The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (36 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

“What kind will you have?” asked the bartender.

“Make it a good one!” I said, not knowing there were several kinds.

It tasted horrible to me, but at the end of five minutes it began to feel good inside my spirit. I definitely dropped the idea of the barber for the afternoon and asked for another cocktail. I then became aware of this astonishing fact: in four months this was the first day I had missed school, and the most stupefying part of it was that this did not give me the slightest feeling of guilt. On the contrary, I had a vague impression that this period was ended, and that I would never return. Something very different was going to come into my life.

In my second cocktail I found a white hair. This moved me to tears, in the euphemistic intoxication produced by the first two cocktails I had drunk in my life. This apparition of a white hair at the bottom of my glass appeared to me to be a good omen. I felt ideas and ideas being born and vanishing, succeeding one another within my head with an unusual speed—as if, by virtue of the drink, my life had suddenly begun to run faster. I said to myself, “This is my first white hair?” And again I sipped that fiery liquid which I had to swallow with my eyes shut, because of its violence. This perhaps was the “elixir of long life,” the elixir of old age, the elixir of the anti-Faust.

I was sitting in a dark corner from which I could easily observe everything, without being observed—which I was able to verify, as I had just said “elixir of the Anti-Faust” aloud and no one had noticed it. Besides, there were only two persons in the bar in addition to myself—the bartender, who had white hair but seemed very young, and an extremely

emaciated gentleman, who also had white hair, and who seemed very old, for when he lifted his glass to his lips he trembled so much that he had to take great precautions not to spill everything on the floor. I found this gesture, betraying a long habit, altogether admirable and of supreme elegance; I would so much have liked to be able to tremble like that! And my eyes fastened themselves once more on the bottom of my glass, hypnotized by the gleam of that silver hair. “Naturally I’m going to look at you close,” I seemed to say to it with my glance, “for never yet in my life have I had the occasion, the leisure, to take a white hair between my fingers, to be able to examine it with my avid and inquisitorial eyes, capable of squeezing out the secret and tearing out the soul of all things.”

I was about to plunge my fingers into the cocktail with the intention of pulling out the hair when the bartender came over to my table to place two small dishes on it, the one containing olives stuffed with anchovies, the other

pommel souglées.

“Another?” he asked with a glance, seeing that my glass was less than half full.

“No thanks!”

With a ceremonious gesture he then wiped up a few drops that I had spilled on the table and went back to his post behind the bar. Then I plunged my forefinger and my thumb into my glass. But as my nails were cut very, very short it was impossible for me to catch it. In spite of this I could feel its relief; it seemed hard and as if glued to the bottom of the glass. While I was immersed in this operation an elegant woman had come in, dressed in an extremely light costume with a heavy fur hanging around her neck. She spoke familiarly, lazily to the bartender. Full of respectful solicitude, the latter was preparing for her something that required a great din of cracking ice. I immediately understood the subject of their conversation, for an imperceptible glance cast by the bartender toward the spot where I was sitting was followed after a short interval by a long scrutinizing gaze from the lady. Before fixing her eyes on me with an insistent curiosity she let her eyes wander lazily around the entire room, resting them on me for a mere moment, meaning in this clumsy way to make me believe it was by pure chance that her gaze settled on me. With his eyes glued to the metal counter, the bartender waited for his companion to have time to examine me at her leisure, and then, with rapid words and an ironic though kindly smile, he told her something about me which had exactly the effect of making the woman’s face turn in my direction a second time. This time she did it with the same slowness, but without taking any precautions. At this moment, exasperated as much by this scrutinizing gaze as by my clumsiness in not being able to get out the white hair, I pressed my finger hard against the glass and slowly pulled it up, slipping it along the crystal with all my might. This I could do without being seen, for a column concealed half of my table from the lady and the bartender just at the spot where my hand and my glass happened to be.

I did not succeed in detaching the white hair, but suddenly a burning pain awakened in my finger. I looked, and saw a long cut that was beginning to bleed copiously. Out of my wits, I put my finger back into the glass so as not to spatter blood all over my table. I instantly recognized my error. There was no hair at the bottom of my glass. It was simply a very fine crack that shone through the liquid of my accursed cocktail. I had cut myself by mistake in sliding the flesh of my finger hard along this crack, with the impulsive pressure which the lady’s second glance had increased in intensity. My cut was at least three centimetres long and it bled uniformly and without interruption. My cocktail became almost instantly colored a bright red and began to rise in the glass.

I was sure I knew what the bartender had said to the lady. He had told her that I was most likely a provincial who had dropped in here by chance, and that not knowing what kind of cocktail to order I had naively asked him to “make it a good one.” In spite of the distance I could have sworn that I had seen exactly these syllables emerge from between the bartender’s lips. At the moment when he finished telling his anecdote my blood had begun to color my drink, making it rise, and my hemorrhage continued. Then I decided to tie a handkerchief round my finger. The blood immediately went through it. I put my second and last handkerchief over it, making it tighter. This time the spot of blood which appeared grew much more slowly, and seemed to stop spreading.

I put my hand in my pocket and was about to leave, when a Dalinian idea assailed me. I went up to the bar and paid with a twenty-five peseta bill. The bartender hastened to give me my change—my drink was not more than three pesetas. “That’s all right,” I said with a gesture of great naturalness, leaving him the whole balance as a tip. I have never seen a face so authentically stupefied. Yet I was already familiar with this expression; it was the same that I had so often observed with delight on the faces of my schoolmates when as a boy I had exchanged the famous ten-centimo pieces for fives. This time I understood that it worked “exactly” the same way for grown-ups and I at once realized the supremacy of the power of money. It was as if by leaving on the bar the modest sum of my disproportionate tip I had “broken the bank” of the Hotel Ritz.

But the effect I had produced did not yet satisfy me, and all this was but the preamble to that Dalinian idea which I announced to you a while ago. The two cocktails I had just drunk had dissipated every vestige of my timidity, all the more so as I felt after my tip that the roles were reversed and that I had become the author of intimidation. An assurance and perfect poise now presided over the slightest of my gestures, and I must say that everything I did from this moment until I reached the doorstep was marked by a stupefying ease. I could read this constantly on the face of the bartender as in an open book.

“And now I should like to buy one of those cherries you have there,” I said pointing to a silver dish full of the candied fruit.

He respectfully put the dish before me. “Help yourself, Señor, take all you want.”

I took one and placed it on the bar.

“How much is it?”

“Why, nothing, Señor. It’s worth nothing.”

I pulled out another twenty-five peseta bill and gave it to him. Scandalized, he refused to take it.

“Then I give you back your cherry!”

I put it back into the silver dish. He reached the dish over to me, beseeching me to put an end to this joking. But my face became so severe and contracted, so offended, so stony, that the bartender, completely bewildered, said in a voice touched with emotion,

“If the Señor absolutely insists on making me this further present. . .”

“I insist,” I answered in a tone which admitted of no argument.

He took my twenty-five pesetas, but then I saw a rapid gleam of fear flash across his face. Perhaps I was a madman? He cast a quick glance at the lady seated beside me at the bar whom I could feel staring at me hypnotically. I had not looked at her for a single second, as though I had been completely unaware of her presence. But now it was to be her turn. I turned toward her and said,

“Señora, I beg you to make me a present of one of the cherries on your hat!”

“Why, gladly,” she said with agile coquettishness, and bent her head a little in my direction. I took hold of one of the cherries and began to pull it. But I saw immediately that this was not the way to do it, and remembered my long experience with such things. My aunt was a hatmaker, and artificial cherries had no secrets for me. So instead of pulling, I bent the stem back and forth until the very slender wire that served as its stem broke with a snap, and I had my cherry. I performed this operation with a prodigious dexterity and with a single hand, having kept my other, wounded, hand buried in the pocket of my coat.

When I had obtained my new artificial cherry I bit it, and a small tear revealed the white cotton of its stuffing. Having done this, I placed it beside the real cherry, and fastened the two together by their stems, winding the wire stalk of the false one around the tail of the real one. Then, to complete my operation, I picked off with a cocktail straw a little of the whipped cream that covered the lady’s drink and applied it to the real cherry, so that now the real and the false both had a white spot, the one of cream and the other of cotton.

My two spectators followed the precise course of all these operations breathlessly, as if their lives had hung on each of my minute manipulations.

“And now,” I said, solemnly raising my finger, “you will see the most important thing of all.”

Turning round, I went over to the table I had just occupied and, taking the cocktail glass filled with my blood, and holding my hand around it, carried it cautiously and daintily put it down on the metal top of the bar; after which, quickly removing my hand from it and picking up the two cherries by their joined stems I plunged them into the glass.

VII. My Rare Works

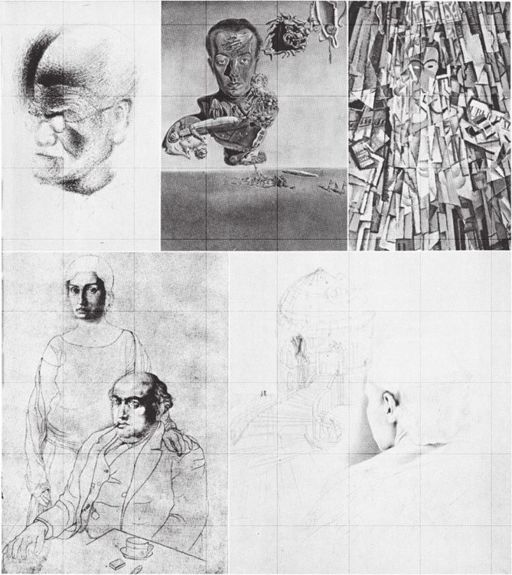

Portrait of Sigmund Freud, clone on blotting paper in London a year before his death.

My first Surrealist portrait: Paul Eluard, at Cadaques in 1929.

Self-Portrait, my first Cubist painting, clone in 192o. Portrait of my Father and Sister, my first pencil drawing.

My first “architectural drawing,” inspired by the contours of Gala’s head.

VIII. The Tragic Implications of Spain

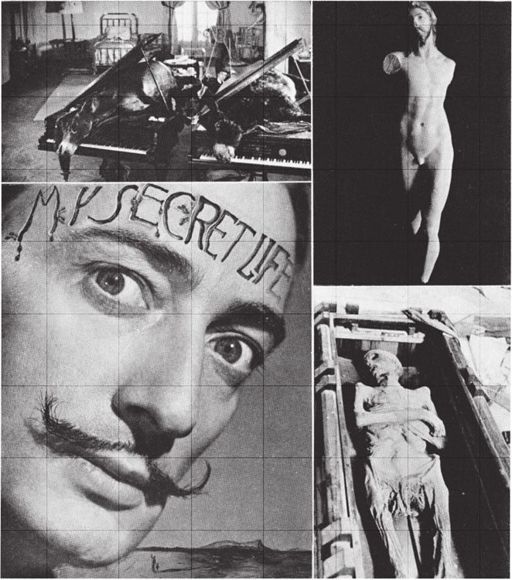

“Le Chien Andalou,” first Surrealist film by Dali and Butmel: asses putrefying on pianos.