The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (58 page)

Read The Secret Life of Salvador Dali Online

Authors: Salvador Dali

At the moment when I arrived in Paris, the intellectual elements were rotten with the nefarious and already declining influence of Bergsonism which, with its apology of instinct and of

l’élan vital

(the life urge), had led to the crudest esthetic revaluations. Indeed an influence blown over from Africa swept over the Parisian mind with a savage-intellectual frenzy that was enough to make one weep. People adored the lamentable instinctive products of real savages! Negro art had just been enthroned, and this was accomplished with the aid of Picasso and the surrealists! When I reflected that the heirs of the intelligence of a Raphael Sanzio had fallen into such an aberration, I blushed with shame and rage. I had to find the antidote, the banner with which to challenge these blind and immediate products of fear, of absence of intelligence and of spiritual enslavement; and against the African “savage objects” I upheld the ultra-decadent, civilized and European “Modern Style” objects. I have always considered the 1900 period as the psycho-pathological end-product of the Greco-Roman decadence. I said to myself: since these people will

not hear of esthetics and are capable of becoming excited only over “vital agitations,” I shall show them how in the tiniest ornamental detail of an object of igoo there is more mystery, more poetry, more eroticism, more madness, perversity, torment, pathos, grandeur and biological depth than in their innumerable stock of truculently ugly fetishes possessing bodies and souls of a stupidity that is simply and uniquely savage!

And one day, in the very heart of Paris, I made the discovery of the 1900 subway entrances, which unfortunately were already in the course of being demolished and replaced by horrible modern and “functional” constructions. The photographer Brassai made a series of pictures of the ornamental elements of these entrances, and people simply could not believe their eyes, so “surrealistic” was the Modern Style becoming at the dictate of my imagination. People began to look for 1900 objects at the

flea market, and one would occasionally see, timidly rising beside a grimacing mask from New Guinea, the face of one of those beautiful ecstatic women in terra cotta tinted in verdigris and moon-green. The fact is that the influence of the 1900 period was beginning to make itself felt in the form of a steadily growing encroachment. The modernizing of Chez Maxim’s, which was becoming increasingly popular again, was interrupted; reviews of the 1900 epoch were revived, and the songs of this same epoch returned to favor. People speculated on the gamey and anachronistic side of 1900 in serving us literature and films in which sentimentalism and humor were combined with naïve malice. This was to culminate a few years later in the collections of the

couturière

, Elsa Schiaparelli, who succeeded in partially imposing the terribly inconvenient fashion of wearing the hair up in back—completely in accord with the 1900 type of morphology, which I had been the first to preach.

I thus saw Paris become transformed before my eyes, in obedience to the order I had given at the moment of my arrival. But my own influence has always outdistanced me to such a point that it has been impossible for me to convince anyone that this influence came from me. It was a phenomenon similar to the one I experienced on my second arrival in New York, upon observing that the window-displays of the great majority of shops in the town were visibly under the surrealist influence, and yet at the same time definitely under my personal influence. But the constant drama of my influence lies in the fact that once launched it escapes from my hands, and I can no longer canalize it, or even profit by it.

I found myself in a Paris which I felt was beginning to be dominated by my invisible influence. When someone, who until then had been very modern, spoke disdainfully of functional architecture, I knew that this came from me. If someone said in any connection, “I’m afraid it will look modern,” this came from me. People could not make up their minds to follow me, but I had ruined their convictions! And the modern artists had plenty of reason to hate me. I myself, however, was never able to profit by my discoveries, and in this connection no one has been more constantly robbed than I. Here is a typical example of the drama of my influence. The moment I arrived in Paris, I launched the “Modern Style” in the midst of the most hilarious hostility. Nevertheless the

prestige of my intelligence was gradually imposing itself. After a certain time it began to take, and I was able to perceive my imprint here and there merely in walking about the streets: laces, night clubs, shoes, films—hundreds of people were working and earning an honest living as a result of my influence, while I myself continued to pace the streets of Paris without being able to “do anything.” Everyone managed to carry out my ideas, though in a mediocre way. I was unable to carry them out in any way at all! I should not even have known how or where to turn to find the last and most modest place in one of those 1900 films that were about to be produced with a prodigality of means and stars, and that but for me would never have been made.

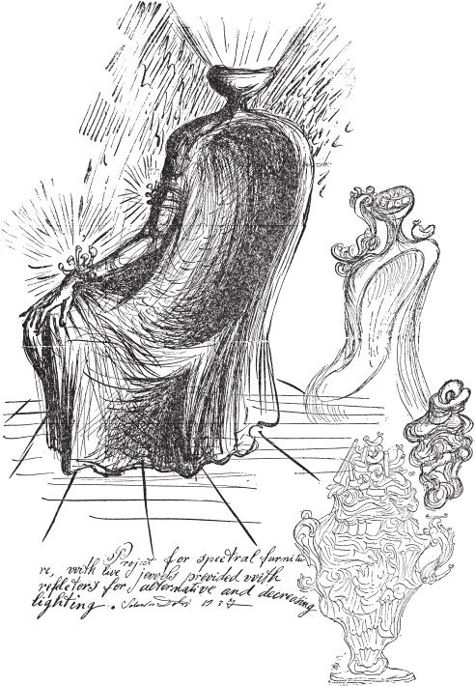

This was the discouraging period of my inventions. More and more the sale of my paintings was coming up against the freemasonry of modern art. I received a letter from the Vicomte de Noailles which made me foresee the worst difficulties. I therefore had to make up my mind to earn money in another way. I drew up a list of the most varied inventions, which I considered infallible. I invented artificial fingernails made of little reducing mirrors in which one could see oneself. Transparent manikins for the show-windows, whose bodies could be filled with water in which one would put live gold fish to imitate the circulation of the blood. Furniture in bakelite molded to fit the contours of the buyer. Ventilator sculptures modeled by forms in rotation. Camera masks for news reporters. Zootropes with animated sculpture. Kaleidoscopic and spectral spectacles through which one would see everything transformed, to be used on automobile rides when the scenery became too boring. Cleverly combined makeup to eliminate shadows and make them invisible. Shoes provided with springs to augment the pleasure of walking. I had invented and worked out to the last detail the tactile cinema which would enable the spectator by an extremely simple mechanism to touch everything in synchronism with what he saw: silk fabrics, fur, oysters, flesh, sand, dog, etc. Objects destined for the most secret physical and psychological pleasures. Among the latter were distasteful objects intended to be thrown at the wall when one was in a rage, and that would break into a thousand pieces. Others were built entirely of hard points and were intended by their jagged appearance to provoke feelings of exasperation, grinding of teeth, etc., such as one experiences in spite of oneself at the noise made by a fork rubbed hard against the marble top of a table. These objects were made to exasperate the nerves to the limit, while preparing the agreeable discharge which the mind would experience at the moment of throwing the other kind of object that breaks so gratifyingly with the pleasant noise of a bottle being opened—plop!

1

I had also invented objects which one never knew where

to put (every place one chooses immediately appearing unsatisfactory), intended to create anxieties that would cease only the moment one got rid of them. It was my contention that these objects would have a great commercial success, success, for everyone underestimated the unconscious masochistic buyer who was avidly looking for the object capable of making him suffer in the most indefinite and least obvious way. I invented dresses with false insets and anatomical paddings calculatingly and strategically disposed in such a way as to create a type of feminine beauty corresponding to man’s erotic imagination; I had invented false supplementary

breasts budding from the back—this could have revolutionized fashion for a hundred years, and still might. I had invented a whole series of absolutely unexpected shapes for bath-tubs, of bizarre elegance and surprising comfort—even a bath-tub without a bath-tub made of a waterspout of artificial water which one would step into and emerge from bathed. I had made a whole catalogue of streamlined designs for automobiles, which were those that would be called streamlined ten years later.

These inventions were our martyrdom, and especially Gala’s. Gala, with her fanatical devotion, convinced of the soundness of my inventions, would start out every day after lunch with my projects under her arm, and begin a crusade on which she displayed an endurance that exceeded all human limits. She would come home in the evening, green in the face, dead tired, and beautified by the sacrifice of her passion. “No luck?” I would say. And she would tell me everything, patiently and in the smallest details, and I have the remorse of not always having been just in appreciating her unsparing and limitless devotion. Often we would have to weep, before going to appease our worries and the epilogue of our reconciliation in the stupefying darkness of a neighborhood cinema.

It was always the same story. They would begin by saying that the idea was mad and without commercial value. Then, when Gala with all the efforts and the ruses of her eloquence had in the course of several insistent visits succeeded in convincing them of the practical interest of my invention they would inevitably tell her that the thing was interesting in theory but impossible to carry out practically, or else, in case it happened to be possible to carry out, it would be so expensive that it would be madness to market it. In one way or another the word “mad” always cropped up. Discouraged, we would definitely abandon one of our projects, which had already cost Gala so much perseverance, and with fresh courage we would launch another of my inventions. The false fingernails did not go; let us now try the kaleidoscopic spectacles, the tactile cinema, or the new automobile design. And Gala, hurrying to finish her lunch, would give me a kiss before starting out on the pilgrimage of the buses, kissing me very hard on the mouth, which was her way of saying “Courage!” And I remained the whole afternoon painting the picture I happened to be working on, of an untimely and anti-modern character, while the uninterrupted cavalcade of unrealizable projects passed through my head.

And yet all my projects were realized, sooner or later, by others; but invariably so badly that their execution would sink into anonymity, the disgust which they created making it impossible to do them over again. One day we learned that false fingernails for evening wear had just become the fashion. Another day someone came bringing the news, “I’ve just seen a new type of car-body”—whose lines were exactly in the spirit of the models I had designed. Another time I read, “Display windows have recently been featuring transparent manikins filled with live fish.

They remind one of Dali.” This was the best that could happen to me, for at other times it was claimed that it was I who in my paintings imitated ideas which had in fact been stolen from me! Everyone preferred my ideas when, after having been progressively shorn of their virtues by several other persons, they began to appear unrecognizable to myself. For once having got hold of an idea of mine, the first comer immediately believed himself capable of improving on it.