The Seventh Angel (6 page)

Authors: Jeff Edwards

Doyle brushed a speck of lint from the lapel of her gray silk business suit. “That doesn’t make any sense,” she said. “China already

has

the bomb. They don’t

need

to get it from Russia, and certainly not from a Podunk province like Kamchatka.”

“

It’s not that simple,” the national security advisor said. “China

does

have the bomb. But not the kind of bomb they

want

. Their nuclear weapons are all single warhead configurations; each missile carries one nuclear warhead. But they’ve been trying since the eighties to develop

MIRV

technology, or

multiple independently-targeted reentry vehicles

. One missile can carry multiple nuclear warheads, and strike several different targets at the same time. The People’s Republic of China has poured a lot of time and money into MIRV research, but they haven’t been able to make it work. Remember the big stink at the Los Alamos National Laboratory in the late nineties? One of our scientists was caught trying to pass nuclear secrets to China.

That’s

what the Chinese were after. MIRVs.”

General Gilmore smiled ruefully. “In the minds of a lot of the minor nuclear powers, MIRV technology has become the admission ticket to the grown up table. The United States has MIRVs. Russia, Great Britain, and France have them. But Israel doesn’t. India, Pakistan, and North Korea don’t. And neither does China.”

“

Okay, the Russians have this MIRV technology, and the Chinese want it,” Doyle said. “Does it necessarily follow that the governor of Kamchatka can deliver it to them?”

“

We don’t know yet, ma’am,” the analyst said. “But it’s possible. He

did

work in close proximity to the technology at Arzamas-16. And he’s got a fairly significant slice of the Russian Navy’s nuclear arsenal right in his own back yard.”

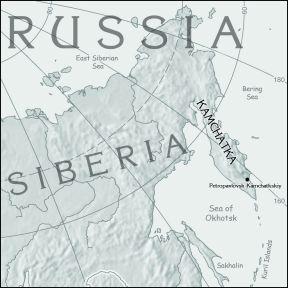

The analyst clicked his remote, and the photo of Oleg Grigoriev was replaced by a map of the Russian Federation. Near the right edge of the map, the Kamchatka peninsula dangled from the southeastern edge of Siberia. The shape of Kamchatka was vaguely like that of Florida, narrow at the northern edge where it connected to the mainland, bulging broadly in the middle, and then tapering to a dagger point at the southern end.

The analyst pressed another button and his remote became a laser pointer. He directed the beam toward the video screen. The red dot of the laser pointer flitted across the map of Kamchatka, and came to rest on a black dot labeled

Petropavlosk-Kamchatkskiy

.

“

This is Petropavlosk, the capital city of Kamchatka.” Another click of the remote brought up a pop-up window to the left of the Kamchatka peninsula. The new window contained a grainy black and white photo of a naval base. A trio of submarines were visible, each moored to a battered concrete pier. “Petropavlosk also happens to be the home port for the Russian Pacific Fleet’s nuclear missile submarines. Based on the latest threat assessments, there are three Delta III class nuclear ballistic missile submarines based in Kamchatka. Each of the Delta III submarines carries sixteen Russian R-29R ballistic missiles, better known to NATO countries as the SS-N-18 Stingray. And each of these missiles is armed with three nuclear weapons, in a MIRV configuration. That works out to 48 nuclear warheads per submarine.”

He paused for a second to let his words sink in; then he looked at the White House chief of staff. “To answer your question more clearly, ma’am, we think there’s a very good chance that Sergiei Zhukov can deliver MIRV technology to China, if that is indeed his intention.”

Veronica Doyle frowned. “Those submarines aren’t under Zhukov’s control, are they? I mean, the Russian military isn’t going to hand command authority for strategic nuclear weapons over to a local politician, right?”

“

No,” said Brenthoven. “Ultimate control of those subs rests in Moscow, with the Russian Ministry of Defense. Local command authority flows through the senior naval officer in Petropavlosk, who takes his orders from Moscow. Provided the Russian command structure remains intact, Zhukov shouldn’t be able to touch those submarines.”

“

Do we have any reason to expect a disruption of the Russian command structure?” the president asked.

Brenthoven rubbed his chin. “We don’t have any specific intelligence about an external threat, Mr. President, if that’s what you mean. But the Russian Navy is having a rough time right now. They’re drastically under-funded. Their sailors are underpaid to begin with, sir. And it’s not at all unusual for them to go months without being paid.”

“

This has been going on for a while, sir,” General Gilmore said. “It’s a problem in all branches of the Russian military, but it’s especially bad in their Navy. The crime rate among their officers is spiraling out of control, and it’s even worse among their enlisted sailors. Extortion, theft, robbery, you name it. Sailors are stealing parts and supplies from their own ships and submarines, and selling them to feed their families.”

The president looked at his national security advisor. “So the deteriorating state of the Russian military could make it vulnerable to destabilization?”

Brenthoven nodded. “That’s a possibility, sir.”

“

It’s a very

real

possibility,” General Gilmore said. “Not so much in places like Moscow, or Vladivostok. The Russians pour a lot more effort and resources into maintaining their military units stationed in high-visibility areas. But some of the obscure bases in Siberia, the Urals, and Kamchatka get little or nothing these days. When people get hungry enough, and desperate enough, the system starts to break down.”

“

This is the twenty-first century,” said the White House chief of staff. “Russia may not be the great Soviet Empire any more, but it’s still a major industrial nation. Conditions can’t possibly be as bad as all that.”

“

Yes they can,” the secretary of homeland security said quietly. “Look at how quickly and utterly our own infrastructures broke down when Hurricane Katrina wiped out New Orleans. Evacuation systems failed; communications failed; emergency relief efforts were overwhelmed; police officers deserted their posts. Hell, in some parishes, the police were looting and shooting right alongside the nut jobs and the criminals.”

She shook her head. “We tell ourselves that we’re beyond such things, but we’re not. The fabric of civilization is much thinner and more fragile than we’d like to believe. And, if the system can break down in the most powerful and prosperous nation on the planet, it can certainly happen to the Russians.”

The president stared at the video screen—the Russian nuclear missile submarines superimposed over the map of the Kamchatka peninsula. “Do we have any reason, beyond oblique hints by Mr. Grigoriev, to suspect a legitimate connection between China and the Governor of Kamchatka?”

“

What little evidence we have is almost entirely circumstantial,” the national security advisor said. “But the medical team at the embassy in Manila pulled a half-dozen 5.8mm military rounds out of Oleg Grigoriev. Ballistic analysis tells us that the bullets were fired from a short-barreled Type 95 assault rifle, the same configuration favored by the Special Operations Forces of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.” Brenthoven closed his leather-bound notebook and tucked it into the pocket of his jacket. “That doesn’t

prove

that the shooters were Chinese military, but it certainly seems to fit the scenario. If Grigoriev is telling the truth, it makes sense that the Chinese would try to shut him up.”

The president scanned the faces of the people gathered around the table. “We’re smelling a lot of smoke, but I don’t see any fire. I’m not saying that it’s not there, but I can’t see it yet. If one of you can connect the dots on this Kamchatka-China thing, now is the time to speak up.”

No one spoke.

“

Okay,” the president said. “Keep on this, Greg. Maybe it’s nothing, but I’m not ready to make that call yet.” He nodded to the analyst. “Let’s move on. What’s next?”

The analyst keyed his remote, and the pictures on the video screen were replaced by an image of a small submarine hanging from a launch and recovery crane on the fantail of a white-hulled oceanographic research ship. “Mr. President, this is the deepwater submersible

Nereus

…”

The president sighed. Submarines.

Why

did it always have to be submarines?

USS TOWERS (DDG-103)

NORTHERN PACIFIC OCEAN (SOUTH OF THE ALEUTIAN ISLANDS)

TUESDAY; 26 FEBRUARY

0947 hours (9:47 AM)

TIME ZONE -10 ‘WHISKEY’

“

How much oxygen have they got left?” The voice came from one of the half-dozen or so khaki-clad men and women milling around near the ship’s boat deck. Ann Roark made a point of ignoring them as she worked through the list of pre-launch procedures to get

Mouse

ready to go into the water.

Some of the onlookers were probably chiefs and some of them were probably officers, but Ann couldn’t tell the difference. It had been a man’s voice, but beyond that, Ann didn’t make any effort to figure out which of the Navy types had spoken. As far as she was concerned, they were all pretty much interchangeable.

The pattern was fairly set now; one of the uniforms would toss out some variation of that question every minute or so, always delivered in hushed tones, and always unanswered. “Do you think they’ve still got air?” “Are they alive?” “How did it happen?” “How bad is the damage?” “Why aren’t they communicating?”

The Navy types weren’t really talking to Ann. They probably weren’t even talking to each other. The whispered questions seemed to be a kind of conversational defense mechanism. By recycling the same unanswerable queries, it was somehow possible to imagine that the crew of the

Nereus

was still alive. When the questions stopped, the mental images began to filter in: two men and one woman lying dead in the darkened confines of the tiny submarine.

Ann didn’t indulge in the useless string of unanswerable questions. She had her own mindless litany: a statement, not a question. “This is not supposed to be a rescue,” she said through her teeth. Her breath came out like smoke in the cold Alaskan air. “This is not supposed to be a rescue. This is not supposed to be a freaking rescue!” She had repeated those words to herself at least fifty times, as though blind repetition could alter the situation.

She moved carefully as she worked. There was frost on the deck, and she didn’t want to slip and fall on her ass in front of all these Navy yahoos. They’d laugh about

that

for forty years, wouldn’t they?

Mouse

hung from the heavy steel arm of the boat davit, swinging gently from the cable that was ordinarily used to raise and lower the ship’s two

R

igid-

H

ulled

I

nflatable

B

oats. The robot was bright yellow, disk-shaped, and about seven feet in diameter. A pair of large multi-jointed manipulator arms protruded from the leading edge of the disk, and three pump-jet propulsion pods were mounted to the trailing edge in a triangular formation. The forward end of the robot was arrayed with clusters of camera lenses, sonar transducers, and other sensors.

The curve of the machine’s yellow carapace was stamped with the words NORTON DEEP WATER SYSTEMS, and the streamlined black ‘

N

’ of the Norton corporate logo. It was the company’s mark of ownership, there for all the world to see. For all of Ann’s personal sense of ownership, Mouse belonged to Norton, not to her.

She unscrewed a waterproof pressure cap from the ventral data port, and plugged a length of fiber-optic into the narrow connecting jack beneath. She plugged the other end of the cable into a hand-held test module about the size of a brick, and began to punch buttons and watch the results on the built-in digital display. The readouts were all in hexadecimal, but Mouse was Ann’s baby. She knew every status code by heart.

Officially, the machine’s name was

M

ulti-purpose

A

utonomous

U

nderwater

S

ystem Mark-I

. Usually, that was shortened to M-A-U-S, or

Mouse

. By classification, it was an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle,

not

a robot. The United States Navy didn’t care for the word

robot

, with its science fiction movie connotations. Consequently, that word was never officially used, and even unofficial use of the

R-word

was discouraged. The machine was either referred to as

Mouse

, or by one of several more generic designations: the

unit

, the

package

, the

system

, the

equipment

, or even the

UUV

. Never the

robot

.