The Shadow Dragons (22 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

“To be fair,” Sigurdsson said, “most of the editions carry your name—everyone just thinks it was a pseudonym for Daniel Defoe.”

“Daniel Defoe murdered me in 1723,” Johnson stated. “He and Eliot were working on a companion book they called the

Pyratlas.

It was to be Eliot’s audition to become the Cartographer’s apprentice, and with me having my own book, Defoe was going to be shut out altogether. So he had me killed, and published the book himself.”

“That’s very interesting,” Sigurdsson said as he made a shushing gesture to his companions out of Johnson’s view. No point in antagonizing the fellow by letting him know they’d just had dinner with his old-friend-turned-adversary. “So how is it you came to be here, in this, ah, state?”

“Apparently, at some point Defoe betrayed Eliot as well, and faked his own death to go into the Archipelago,” said Johnson. “In the years that followed, Eliot’s son, Ernest, had also become a mapmaker, thus continuing in the family trade. What Defoe only discovered later was that the McGees had been hiding secret clues to the pirate treasures in duplicate maps—maps that young Ernest subsequently burned. A few survived, but not enough that Defoe could use them to find the treasures without consulting a second book I had been writing, which I called

The Maps of Elijah McGee.

“Somehow Defoe had discovered a process to resurrect the dead by way of painting their portraits—so he commissioned one of me to ask me the whereabouts of the book. The minute I could speak, I spit in his face.”

“You can spit?” said Archimedes.

“Well, I could make the gesture,” said Johnson. “As long as he knew my intent, it didn’t matter if I couldn’t really spit. Anyroad,” he went on, “after he realized I couldn’t be coerced, he sold me to someone who’d just stolen one of the Dragonships—the

Indigo

Dragon,

I think he called it—so I ended up in the possession of actual pirates. Ironic, isn’t it?”

“That would be a correct assessment,” said the professor. “Did any of these pirates have names?”

“Most of them flat-out ignored me,” Johnson said, “except when they needed something. So I never got more than the occasional name, like ‘Coleridge’ or ‘Blake.’ But I did catch what they called themselves as a whole—they said they were part of the Imperial Cartological Society, and that they’d been commissioned by royalty. That makes them privateers, which is as bad as pirates in my book.”

“I agree,” the professor said, looking somberly at his companions. They were all thinking the same thing: that Defoe, who was among the Caretakers Emeritis, was in league with Burton—and they had no way of telling anyone at Tamerlane house. “Did any of them survive the, ah, sea-beastie attack?”

“I couldn’t tell you,” said Johnson. “After the first blow, I ended up where you see me—and my peripheral vision isn’t what it used to be.”

“I’m impressed that you even made it this far,” said the professor.

“We used your own notes, Professor,” Johnson replied. “Yours, and those of someone called Bert. They were given to the society by someone called Uruk Ko.”

Professor Sigurdsson lowered his head. That was the hat trick. If the Goblin King had aided the Imperial Cartological Society, the Goblins had to be in league with the Winter King’s Shadow.

“The notes,” he said suddenly. “Did any survive the wreck?”

“I doubt it,” said Johnson, “but I can recall most of what was written on them. They had to do with the precautions, I believe.”

“Precautions?” asked Quixote.

“There are seven islands that must be crossed,” said Johnson. “You cannot simply bypass them. Each one is akin to a gate, and gates must be entered properly.”

“I remember,” said the professor. “We’ve come prepared.”

“That’s good,” said Johnson, “since we weren’t. We didn’t take the cautions seriously, and as a result, the

Aurora

was lost.”

“Professor,” Rose whispered, “you have one of the pocket watches—is it possible to release Captain Johnson from the portrait?”

“An interesting thought,” said the professor. “Let’s find out.”

They explained what they wanted to try, and Johnson responded with considerable enthusiasm. Archimedes retrieved several scraps of cloth and timber from the wreck, and Quixote fashioned a sort of sling-on-a-pole to scoop up the portrait.

It took only a few tries for him to succeed, but when they had the picture onboard, their expressions fell.

There was no place on the frame to insert the watch. Johnson was trapped within.

“That’s all well and good,” he said. “I’ve gotten used to it, anyway.”

“It may be for the best,” said the professor. “There’s a time limit unless you’re at a particular location. And that would literally ruin your week.”

“Will you still take me with you, anyroad?” asked Johnson. “I’m really tired of seeing the same fish and coral day after day, and there’s only been one other person come over the falls since I got here, and he died straightaway. He’s just over there, to the right.”

Quixote steered the

Scarlet Dragon

over to where Johnson had indicated, and sure enough there was a skeleton, facedown in the water. It could not have been there very long, as the coral had not yet begun to form around the bones, and scraps of his clothing that had not yet rotted were still floating about.

“I think this is Wilhelm Grimm,” the professor said sadly. “He must have displeased his master.”

“And he was simply dropped over the waterfall?” Rose exclaimed in horror. “If he died, then what hope do we have of finding Madoc alive?”

“Your father is a man of unusual mettle,” said Sigurdsson, “and I suspect, as Samaranth probably knew, that just dropping him over the falls would not be enough to kill him. The same might not be true for mere mortals like myself.”

“No, look,” said Quixote, pointing. A dagger was lodged firmly between two of the skeleton’s ribs, next to its spine. “He was killed, then discarded. Truly, an ignoble act.”

“Do you think it was Burton who did it?” Rose asked quietly. “Or someone else?”

“Whoever it was, my dear child,” the professor said, turning her away from the sight, “this person is past worry. The troubles of this world are no longer his.”

“Pardon,” said Quixote, “but that is a strange platitude to hear from someone who is himself dead.”

“I am a Caretaker,” Sigurdsson replied. “The troubles of this world

are

my business.”

No one spoke any further, and Quixote adjusted the sails, pointing the little craft to the west.

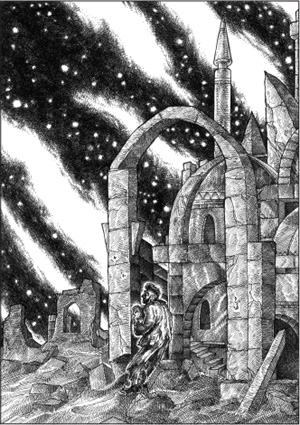

Standing among the ruins was a man, dressed in rags . . .

The Ruined City

The portrait

of Charles Johnson struck up an immediate friendship with Archimedes, who was fascinated by the tales of pirates and privateers. Their Golden Age, which had been documented by Johnson, Defoe, and the McGees, was an era that the owl had missed completely when Jack and John had brought him into the future with Rose.

“You actually hid clues to the treasures in the maps themselves?” Archimedes asked. “Ingenious!”

“It was Ernest’s idea,” said Johnson, “because of his connection to the Empress Josephine, and Napoleon’s hidden fortune.”

“You’re more interesting than most portraits I’m acquainted with,” said the owl.

“Thank you,” said the captain.

With Johnson thusly preoccupied at one end of the boat, the professor, Quixote, and Rose were able to discuss their concerns with a bit more privacy.

“The

Aurora

belonged to the Goblins,” said the professor. “If Burton was able to procure it from them, along with my notes, it’s all but certain they are in league together.”

“What worries me more,” Quixote mused, “is what Johnson told us about Defoe. That isn’t the behavior of a Caretaker.”

“It isn’t,” said the professor, “but we shall just have to trust in the Caretakers’ ability to look after themselves. We have a hard enough task of our own.”

“Heads up,” Johnson called. “We’re approaching the first gate.”

The first of the seven gates was a lighthouse.

“That’s rather small for an island, and rather odd for a gate,” said Quixote.

“It’s a most important one,” said the professor, “and one I’m guessing the society disregarded.”

“I tried to tell them,” Johnson said, sighing, “but they wouldn’t listen.”

“What must we do?” said Quixote.

The professor picked up the tallow lantern. “Simply take this to the room at the top and replace the lantern that’s there.”

Quixote looked at him in surprise. “That’s all?”

The professor nodded. “That’s all. But hold fast to the empty lantern. It’s our receipt, so to speak.”

“On whose account?”

“This is the land of the dragons,” said the professor. “Somewhere up there in the darkness, they’re watching. And somewhere here below as well. The lantern is marked with the letter

alpha,

and replacing a light in the lighthouse is a show of our good intentions.”

“Sort of like leaving the milk out for the faery folk, or the brownies,” said Rose. “I think I understand.”

Quixote hopped from the boat to the narrow steps of the lighthouse and quickly ascended the steps. While the others waited, they scanned the waters around them for any signs of life, and it was Johnson who found it.

“Oh, dear,” he moaned. “Look.”

They looked in the direction Johnson was facing and saw a rising swell of water. Something massive was swimming just under the surface, and it was coming toward the

Scarlet Dragon.

It grew closer, and larger, and the professor was just about to suggest deploying the balloons on the boat when a brilliant beam of light cut through the gloom above their heads. The light shone in two directions: one beam back toward the waterfall, and the other forward to the west.

The swell disappeared.

“Whew,” said Johnson, as Quixote descended the steps with the empty lantern and rejoined them. “That was excellent timing.”

“I’m sorry it took as long as it did,” Quixote replied. “I forgot to take a match. Fortunately, someone had left some behind.”

He held up a small brown coin purse. “There were a few matches inside, along with some coins and a few pebbles,” he said. “We got lucky.”

“The luck is accidental,” the professor said, taking the small purse. “I must have left it there myself. I’ve been wondering what happened to it for decades.

“Here, look,” he said, examining the contents. “This round black quartz is actually the tear of an Apache princess that I found in Arizona. And this”—he held up a small white stone—“I took from a stream in France that is said to cure all ills and heal all wounds.”

“And the coins?” asked Quixote. “Of what significance are they?”

“I kept those in case I needed to buy an ale,” said the professor. “This adventuring life is hard work, and it makes one very thirsty.”

With the offering to the dragons made, they sailed on toward the next island gate.

“Professor,” Rose asked suddenly, “do you know what time it is?”

“I’m not sure if time works the same way here as it does up top,” the professor replied. “Worry not, dear Rose. We’ll get there, by and by.”

“But professor,” Rose started to say.

“There,” the professor interrupted, pointing. “The second gate!”

The next island was wildly overgrown with foliage and was almost perfectly divided down the middle by a large swamp.

“Anything dangerous here?” asked Quixote.

“The usual,” said the professor. “Ligers and tigons, and the occasional gorilla, who will leave you be if you throw the names of books at them.”

“Throw books?” asked Rose.

“No,” said the professor, “just the names. They’re usually content with those. The only creatures to watch out for here are the crocodiles—they fly, you know.”

Sure enough, the moment the

Scarlet Dragon

moved into the swamp, the air was suddenly filled with winged crocodiles. They swooped and wove as if they were a great flock of leathery cranes, flying south for the winter.

It took only seconds for them to focus their attention on the tiny boat and its edible occupants, and they changed their formation to envelop the

Scarlet Dragon.

Before the others could react, the professor reached into a satchel and flung a handful of small objects into the air. The crocodiles immediately dispensed with the formation to chase the treats. Professor Sigurdsson threw two more handfuls for good measure, and soon all the flying crocodiles had retreated into the jungle.

Rose peered inside the satchel. “Lollipops?”

“Indeed. The crocodiles here are fond of lollipops,” the professor explained, “and I made certain to raid the store of them Bert keeps onboard the

White Dragon

so that we’d be prepared.”

“I don’t think it likely that you carried many lollipops on your first voyage here in the

Aurora,

” said Quixote, “so how did you discover the crocodiles’ weakness for them?”

“Completely by accident, I assure you,” replied the professor. “As we were fighting them off, one of the crew was yanked overboard—and it was in watching the crocs tear the poor devil to pieces that we realized what they were really after.”

“The lollipops,” said Rose.

“Just so,” said the professor. “He had a penchant for them. Claimed it kept him from eating too much, as he hoped to keep his weight down. Ironic, isn’t it?”

“This is not a gate where we must pay a toll to get through,” the professor said at the third island. “To pass here, one must simply resist the urge to take something.”

“How do you mean, professor?” asked Rose.

“I’ll show you,” he said, “but this is a place we’d best cross in the air.”

He and Quixote deployed the balloons, and the little craft rose into the air.

The island was small, and unremarkable in most respects. It had palm trees, sandy beaches, and a few gently rolling hills. And in the center was a large, glistening lake.

“Look,” he said, pointing over the edge of the

Scarlet Dragon

at the water below.

The lake was filled with gold.

Not just raw ore, or coins, but every manner of object one could think of: fruit, and fish, and mugs, and swords, and on and on—all made of the gleaming yellow metal.

“A pirate’s repository, perhaps?” asked Quixote.

“No,” said the professor. “Death. The waters here bring death. Look farther.”

All around the edges of the lake were larger golden masses, which the companions had at first assumed to be simple piles of gold. But they weren’t—they were people.

“The water turns everything it touches into gold,” said the professor, “including those who seek to take some of it for themselves.”

Quixote was holding Johnson so that he could also see the spectacle below. “Look!” the captain said. “There’s one of those sorry privateers!”

Professor Sigurdsson looked more closely, then lowered the

Scarlet Dragon

a few yards.

“Hmm,” he said. “That’s William Blake, unless I miss my guess. Surprising—I would’ve thought he had a stronger will than that.”

In a few more minutes they had passed over the lake, and the professor said it was safe to drop back into the waters past the western beach.

According to Johnson’s memory of the professor’s notes, the next island gate had a name. “It’s called Entelechy,” he said.

“Both are,” said the professor. “The island, and its queen. They share the same name—although it’s more politic to refer to her as ‘the Quintessence.’ As far as I know, she’s Aristotle’s goddaughter, and so is at least two thousand years old.”

“Finally,” said Rose. “I’ll get to meet someone my own age.”

Entelechy was a prim and proper island, with a well-kept harbor and several soaring towers of blue stone. They stopped at the dock and left Archimedes and Captain Johnson to guard the boat. The professor led the others to a great turquoise-tinged reception hall.

The Quintessence was seated on a throne at the head of a magnificent banquet table. She was perhaps twelve feet tall and had all the presence of a giant. Her gown billowed around her immense chair, and her hair was piled high above a glittering crown.

“Great Quintessence,” the professor said, bowing. “We seek passage through your gate, if you please.”

“Come closer,” she commanded, “that I may better see you.”

A curious look of . . . happiness appeared on the queen’s face as she watched the professor. She considered them all, briefly, then turned back to Rose.

“You have the look of the Old World to you, girl,” she said. “I may allow you to pass. Who are your forebears?”

“My father’s father was Odysseus,” she replied.

“Ah,” said the queen. “I might have guessed. You are familiar to me. And your mother’s parentage?”

“No one you’d know.”

“Hmm,” said the queen. “And you?”

Quixote bowed. “I am the lady’s humble protector,” he said simply.

“I see,” said the queen. “And you?”

“I am a simple traveler,” said the professor, “seeking out what beauty there is in the world.”

“And what have you found?”

“If seeking beauty was my only goal, I should be happy to stop here,” said the professor, “but we have other needs, and thus must go on.”

The queen smiled. “That’s an excellent answer,” she said, smiling. “I believe I will let you pass, for a price.”

“There’s not much left to barter with,” Quixote whispered to the others, “only the candles!”

“Those are for a different gate,” said the professor. “Name your price, milady.”

“Will you give me a kiss?” the queen asked, bending down so he could reach her.

“I shall,” said the professor. And he did.

“Ahh.” The queen sighed. “I have missed that—it was as nice as before, so long ago. It does grow lonely out here, you know,” she said with a look of sorrow on her face. “There have been few other visitors of late.

“Another descendant—or was it an ancestor?—of Odysseus passed this way not long ago, and I allowed him through, because he knew my godfather.”

Rose and Quixote were silently thrilled by this—the first proof they’d had of Madoc’s survival, and passing.

“There was another,” said the queen, “but he was rude, and a bit delusional. I let him pass, but I kept one of his arms.”

“We really ought to be going,” said Quixote, his eyes wide. “Begging your pardon.”

“You won’t stay to dine with me?” said the Queen.

“We really must go,” Rose concurred.

“So we must,” the professor said. He bowed deeply and kissed the queen’s hand.

She bowed her head in assent, and the companions returned to the boat. Shortly after, they were again underway.

“I don’t know what to say, Professor,” Rose said with a broad smile. “That was an impressive display of personal charm.”