The Shadow Dragons (24 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

The professor started, and Madoc laughed.

“I’m only joking,” he said to the old Caretaker. “Really, though—what were you expecting me to say? That I’ve had time to reconsider my choices, and I’ve turned over a new leaf?”

“I’m pretty sure that’s a lie,” said Archimedes.

Madoc rolled his eyes. “Of course it’s a joke, you stupid bird,” he said, more exasperated than irritated. “I used to be the villain of the story, or hadn’t you heard?”

“Actually, you still are, after a fashion,” said Sigurdsson. “Or at least, your Shadow is.”

“Now you have my attention,” Madoc said, sitting cross-legged in the sand. “Tell me.”

The companions sat on the sand across from Madoc, and Professor Sigurdsson told him everything that had happened in the quarter century since the conflict on Terminus.

Several times the professor nearly paused in his narrative, concerned that he might be sharing something that would better remain a secret—but each time he reminded himself that without Madoc’s help, they would not be able to defeat the Shadow King. And while they were still a long way from being friends, or even friendly enemies, Madoc was at least listening to what they had come to say.

“We need your help, Madoc,” the professor said. “Show him, Rose.”

She walked back to the

Scarlet Dragon

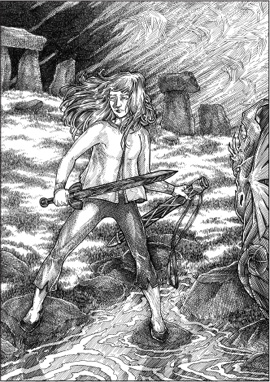

and retrieved a bundle, which she placed on the sand in front of Madoc. Slowly, carefully, she folded back the oilcloth to reveal the shattered remains of the sword Caliburn.

“We need you to repair the sword, Father,” Rose said simply. “Can you do it? Please?”

Madoc stared at the sword for a long moment, as if he couldn’t comprehend what he was seeing. His face was inscrutable, and Quixote and Sigurdsson exchanged worried glances. What did this mean, that he didn’t react at all?

Suddenly Madoc fell to his knees, dropped his head into his hands, and began to shake violently.

Quixote was about to step forward, and Rose was reaching out a hand to comfort him, when they realized together that Madoc was not sobbing.

He was

laughing.

He laughed so hard that he could not speak, could not stand. Tears ran down his face as he erupted in a paroxysm of laughter, choking, sobbing, guffawing, all at once.

“If you only realized, child,” he choked between spasms. “If you only understood how important this object was to me, once . . .”

“We do understand, Madoc,” Sigurdsson began.

“You understand nothing!” shouted Madoc, his anger rapidly sobering him. “Nothing!

“My brother was the one who wished to conquer the world!” he cried. “I only wanted to do what was right! But each time, he forced his way ahead and did as he wanted—only I paid the price!”

“He paid a price too, Father,” Rose said. “He was imprisoned in the Keep of Time, never to leave. And it was his own son who banished him there.”

Madoc blinked at her, as if he didn’t understand. “Arthur?” he said. “Arthur banished him?”

“Yes,” said Rose.

“He—he never said,” Madoc began. “Even when I returned to Camelot, if he had only told me . . .”

“Would that have changed anything?” asked the professor.

Madoc grew cold again. “No,” he said, his voice edged with hatred. “He took my hand, and then he took my wife. He deserved everything I brought down on his house.”

“All you’ve ever brought down is darkness, Madoc,” said the professor. “And that darkness has continued to fester and grow, until it now threatens to cover two worlds. And you still have the ability to choose the right thing.”

“It’s too late for that,” Madoc said, shaking his head. “After what was done to me—”

“Spare me,” said Archimedes. “You were always the rational one, Madoc. But nothing you’ve said is rational in the least. So Merlin wanted to conquer the world, and sacrifice his own son in the process. You defended the boy, then lost your hand trying to kill your brother. And after all that, you set out to basically subjugate everyone else who has ever lived. And you failed at that. So why don’t you show some of the mettle you used to have, and just do the thing you know to be right?”

Madoc glared at the bird and trembled a little, but then he steadied himself and spoke. “All right.”

“All right, what?” said Archimedes.

“It’s very simple,” Madoc said. “I will do as you ask, and repair the sword. But I want you to do something for me.”

“I’ll consider it,” said Rose. “But I cannot promise anything.”

“This is not a negotiation,” said Madoc. “This is a barter. I am the only one who can give you what you want, and so I am asking you for something I want. You either say yes, or you say no. Whatever happens now is entirely up to you.”

“What is it that you want, son of Odysseus?” said Quixote. “Ask, and we shall consider.”

“As I said,” Madoc repeated, “it’s very simple. I’ll repair the sword, and you can go back and defeat whatever evil it is that my Shadow has perpetrated. But when you are victorious, I want you to return to Terminus and drop a door from the Keep of Time over the waterfall.”

“You want us to provide you with a means of escaping your prison, you mean,” said Professor Sigurdsson. “I don’t know if that will be permitted.”

“I’m not asking for escape,” said Madoc, “or else I’d be demanding to return with you now. I know that there are lines no one will cross for me, and if nothing else, I don’t relish the idea of encountering Samaranth again anytime soon. All of which is why I’m asking for the door—any random door will do. It won’t be a means of escape so much as a sort of parole.”

“Freedom is freedom,” said Quixote.

“I say we agree to it,” said Archimedes, who had continued listening and observing during the entire discussion. “I’ve actually known him longer than any of you, and honestly, I always liked him better than the other one.”

At the mention of his brother, Madoc winced, as if the words stung. But he said nothing.

“Even if we do agree,” said Quixote, “where do we find a door from the keep?”

“If this is successful,” the professor said, “then we will have recovered all of the doors that are being hoarded by Burton. We can have our pick of them.”

“And if you’re not successful?” said Madoc. “What then? I will have done this service for you for no benefit to myself.”

“Once you would not have asked a boon for yourself, to do something that cost you so little and helped so many,” the professor replied.

Madoc regarded him with a rueful stare. “That was a different time, and long past. Don’t try to sway me with what cannot be reclaimed.”

“I’ve read the Histories,” the professor said. “I know as much about you as any man, save for my protégés, and I know the caliber of man you once were.”

Madoc brandished his right arm, which bore the tarnished hook. “It was your students whom I have to thank for this,” he said, waving the hook in the air. “And also for making me the man I am now. And that you cannot change.”

“Will you take my word of honor?” Quixote said suddenly. “My word, as a knight, that whatever it may take, we shall deliver you one of the doors?”

Madoc tipped his head back and laughed. “I might, if you were a real knight,” he said brusquely. “Go back and play your little games with windmills and shrubberies and fat, useless squires. There’s nothing for you to promise here.”

“My word then,” offered Sigurdsson. “As a Caretaker of the

Imaginarium Geographica.”

“A bit more appealing, but no,” said Madoc. “Not that I doubt your sincerity, but from what I can gather you appear to be dead— and dead people have a way of living down to one’s expectations.”

“Then will you take

my

word?”

Rose stepped between the knight and the professor and laid a comforting hand on Madoc’s hook. He started to protest, but after a moment lowered it. Rose took his other hand in hers and looked up at him, her face serene.

“I am your daughter,” she said softly. “I am the child you never knew, who was raised by someone you claimed to love. In her name, and on her blood, which also runs in my veins, will you take my word that whatever we must do, we will somehow find a way?”

At first, as she spoke, Madoc would not meet her gaze. Then, slowly, he lifted his eyes to look at her.

“Green,” he said quietly, “flecked with violet. Her eyes were not violet.”

“But yours are, Father.”

He looked at her a moment more, then, almost imperceptibly, he nodded. “Your word I will take.”

“Then we agree,” Rose said. “If you will repair the sword, we will give you one of the doors from the Keep of Time.”

The Return

It was not

by accident that it began in Oxford.

The darkness that began to spread over the cities of Europe covered England first, then moved east.

The Allied forces had been assured that it was all according to some greater plan—but calls to the Chancellor went unanswered, and it was no comfort to them when they received reports that their enemies’ strongholds were also being plunged into darkness.

It had been unsettling enough to receive the strange reports of ships manned by children that appeared and disappeared, mounting raids against friend and foe alike before disappearing into the mists. But this strange darkness was worse, because it had been foretold. It was worse because it was darkness with form, and with purpose.

One by one, the cities of the world were made dark by the shadows of the Dragons.

Hank Morgan watched numbly as the shadows covered Oxford, then London, and Paris, and Berlin, and Cairo, and Amsterdam, and Tokyo, and Rome, and on and on.

He returned to the Kilns in Oxford and looked around at the tumbledown wreck the cottage had become in the last seven years. Reaching behind a cupboard, he retrieved a hidden Trump and quickly began to sketch in the details of a destination he’d been told never to draw.

A few moments later he stepped through the card to Tamerlane House.

With Quixote and Archimedes’ help, Madoc soon had the forge glowing hot. He had several rough but still incredibly inventive tools, which could be attached to his hook for a multitude of uses. Once the coals were turning white with the heat, he waved off the knight and the owl and went to work.

Rose watched from the sand not far away, while Professor Sigurdsson was content to sit in the boat and read. “It’s John’s book, you know,” he said in explanation. “I’d like to finish it before the trip is over.”

Rose knew what he was avoiding saying, and she resented slightly that he was not more direct—but at the same time, she was a little bit grateful for the lie.

Quixote quickly realized that the work Madoc was doing was far beyond his own experience, and he wisely kept his distance. But Archimedes was a different story. The sword, and its original creation, were not so far removed from his own time, and from the culture that had created him.

He offered a word of advice now and again, and eventually Madoc offered him a modified apron to wear to protect him from the showering of sparks, and Archie took an active role in restoring the sword.

Rose watched this in wonderment. Archie had been Madoc’s teacher before he was hers. He had been present when her mother fled Alexandria, during the first betrayal. And now, here he was, centuries later, helping Madoc to create the weapon that would destroy a piece of himself.

Archimedes did not judge him, and was no more or less critical than he was with anyone else.

Is that because he’s mechanical, and not truly alive,

she wondered,

or is there something more? Is it perhaps because he knew Madoc before he was Mordred, before the betrayals— and is helping the man he was, not the man he is?

Is there a difference? And is the difference in the man I see, or in how I choose to see him?

She also looked back at the professor, reading in the

Scarlet Dragon,

and wondered what had motivated

him.

This trip would very likely cost him his existence—an existence that was essentially a second chance at life. But he had risked it to seek out the very man who had killed him, to ask for his help. Why? How could he have believed it was even possible? And yet there Madoc was, doing the very thing they needed the most.

Rose suspected she knew what her uncle John would say if he were here:

This is what it means to grow up, to learn why we do the things we do and make the choices we make. It just comes down to how much you believe in something, and doing it, and not worrying about the outcome.

Come to think of it, she reconsidered, that was more along the lines of what her uncle Jack would say.

Madoc worked for one hour, then two, then four. The sweat was pouring off him in rivulets, and his arms had gone brown with the heat.

Again and again he flipped the sword with the tongs and hammered away at it as if possessed. Slowly, ever so carefully, the pieces of the sword began to coalesce into a whole again.

Finally he swung the hammer high over his head and struck the last blow.

Tossing the tongs to Archimedes, he dropped the hammer in the sand and walked over to the water’s edge.

He stood there for a long moment, examining the glowing red metal. Then he bowed his head. “Thank you, Nimue. Forgive . . .”

Madoc knelt and plunged the sword into the water.

A cloud of steam issued up and enveloped him, and for a moment he was completely enshrouded in the whiteness. But then it evaporated, and he rose to his feet.

Madoc turned around to face the others. In his hand, he held the gleaming black sword Caliburn.

He clenched his jaw. “This is what I wanted,” he said numbly. “This is what I fought for, what I . . .

“Here.” He flipped the blade around to offer the hilt to Rose. “Take it. I no longer want it—not when I know what it’s already cost me, and everyone else who has touched it. Take it.”

But Rose merely stood there with her hands at her side.

“You have the sword Caliburn in your hand,” she said. “You have a Dragonship. You could return and take the throne if you wish. You could defeat your own Shadow easily—and then you would be master of the world.”

Archimedes let out a squawk, and Quixote stared at the girl in astonishment. Was she suddenly insane?

Madoc met her eyes, trying to read what he saw there. She was inscrutable, and worse, there was no guile in her. She was really offering him the sword and the ship.

“Madre de dios,” Quixote muttered.

“Choose,” said Rose.

“I shattered this sword the first time,” Madoc told her evenly, “because I truly believed that was my destiny. I return it to you now, whole and unbroken, because I know that it is not.”

“That,” Rose said as she took the sword from his hand, “is why you were able to hold it at all. And that, if nothing else, means there is worth in you still.”

Quixote raised his eyes heavenward in a silent prayer, then held his hand out to Madoc. “Thank you.”

Madoc looked down at the outstretched hand, then turned his back to the companions and strode over to the forge to start breaking it down.

“What if you need to use it for something else?” said Archimedes. “Shouldn’t you leave it be?”

“I won’t use it again,” Madoc said as he continued his dismantling effort. “Once you’ve repaired the sword of Aeneas and Arthur, everything else is just metal.”

It took only a few minutes for Rose, Quixote, Archie, and the professor to ready the

Scarlet Dragon

for the return voyage home. They wrapped the sword in an oilcloth and secured it under a crossbeam in the prow. Then they went to say good-bye to Madoc.

He had finished dismantling the forge and had strewn the pieces all across the beach. He was standing with his back to them, forty or fifty yards away—far enough that he couldn’t feel them behind him as they prepared to leave, but not so far that the echoing properties of the wall wouldn’t conduct their farewells.

“Thank you, Madoc,” said Archie. “Farewell.”

“I am grateful to you,” said Quixote, “and we shall not forget our promise.”

“I forgive you,” said the professor. “This visit has been far more enjoyable than the last time we met.”

“Good-bye, Madoc,” said Rose. “Good-bye, Father.”

Madoc did not turn around, nor acknowledge that he had heard them.

The four companions boarded the

Scarlet Dragon

and inflated the balloon. In seconds it was aloft and pointed east.

The

Scarlet Dragon

flew rather than sailed, because on this trip there was nothing to search for but the horizon. The little ship sped along through the gloom and mist as quickly as they could compel it to go.

It was difficult to estimate time or distance, because there was no real day or night here—it was all varying degrees of light and dark.

Every so often, one of them would glance over at the bundle under the cross-brace, as if to reassure themselves that they had really done it, that the sword was there, and whole. Once Rose offered to unwrap it, but Quixote placed his hands on hers and shook his head.

“It is not a frivolous thing, to be displayed for our amusement or comfort,” he said. “You will know when the time is right, and you will hold it as it is meant to be held.”

“Also,” said Archimedes, “you might drop it over the edge. And that would be a bad, bad thing.”

“We don’t want to spoil the trip now, do we?” said Professor Sigurdsson.

“Professor,” Rose began to ask—but she could not find the words to finish the question. It didn’t matter. He knew what she wanted to know, and his answer was that he refused to turn and look at her.

“Faster,” Rose whispered to the

Scarlet Dragon.

“We must go faster.”

It was difficult to tell, there in the twilight of the place past the Edge of the World, if the ship was flying any faster because of her prompting, but she felt it was, and that gave her hope.

Their altitude was such that they could not see the waters below, and had no way of knowing if they had passed most or all of the islands. Their only hope was an eastward course—and speed.

The professor fell.

He did not faint, but suddenly his legs would not hold him upright in the boat any longer.

Rose and Quixote knelt next to him and sat him upright. “Are you all right, Professor?” Rose asked. But she could read the answer on his face. He was pale—but not from exertion or anemia. He was beginning to become slightly transparent. Ethereal.

He was starting to fade.

“No, no, no, no,” Rose said, squeezing his hand. “We’re almost there, Professor! You have to hold on!”

He tried to stand, but it was too difficult, and he slumped back down. “Here,” Quixote said, folding the professor’s coat into a pillow. “Lie down a moment. Gather your strength.”

“I fear my strength has all but left me, Don Quixote,” said the professor. “I just wish it wasn’t so dark out here. I suppose it’s all right for the Dragons, but I really prefer the sunshine.”

“Really, Professor?” Rose asked, anxious to keep him talking. “Tell us about it.”

“It was among my greatest joys of living,” Professor Sigurdsson said weakly. “That may sound odd for someone who lived in London, but in my youth, I often traveled to sunnier climes. I had just hoped, when my time finally came, that I would be able to expire in some golden field somewhere.”

“There is such a place,” Quixote said quietly. “I have seen it, and it is the most wonderful place. There is indeed a golden meadow, the most glorious you can imagine, filled with grasses and flowers that cover every inch of earth. And just beyond is a castle made of crystal, where the great heroes of history may go when they have earned their final rest.

“I am certain,” he went on, laying a hand on the professor’s forehead, “that there is a place there for you, my noble friend. And there are three beautiful women who watch over the heroes, so that if any have lost their way, they can help them find the road to Paradise.”

Tears filled Rose’s eyes, and they ran down her cheeks and dripped onto the professor’s face. “Don’t worry, my dear,” he said, consoling her. “Things have happened the way they were meant to. I got to see my dear friends one last time. I was able to make peace with the man who murdered me. And I got to be a hero one final time. There is nothing more I could have asked or expected in this world or any other, and truly, I am content.”

“A light!” Archimedes shrieked. “I see a light!”

The companions looked past the prow of the ship to see what had gotten the owl so excited—and then they became excited themselves. There was indeed a light.

The edge of the waterfall was in sight.

Rising swiftly out of the darkness, the light that spilled over from the Archipelago created an artificial horizon—but it was still distressingly far away.

“We’re going to make it, Professor,” Rose said, gripping his hand. “I know it.”

But he shook his head, and touched her cheek. “My dear, we might—just might—make it to the surface again, but it will be too long a journey back to the Nameless Isles for me to survive. You must accept this.”

She bit her lip and nodded, then hugged the old man tightly, for she knew it would be her last opportunity to do so.

“Is there anything I might do?” Quixote asked.

“Just one thing,” the professor answered. His voice was little more than a whisper now. “I don’t want to go while I’m lying here on my back. Will you help me to stand?”

“Of course, my friend.”

Together, Quixote and Rose lifted Professor Sigurdsson up until he was on his feet, but he was already too weak.

“It’s all right,” he said, slumping in their arms. “I can meet my fate sitting.”

“You shall not!” said Quixote. “Not while I am with you. By God, you will stand!”