The Shadow Dragons (9 page)

Read The Shadow Dragons Online

Authors: James A. Owen

As he drew, the lines of the cloudy apple ink left only a shiny, moist indication that quill had touched skin; but as he sketched his way down the right side of Charles’s back, a curious transformation began to happen on the left.

The lines wavered, faded, then solidified into a rich, reddish-brown color, much like the lines in the older maps of the

Geographica.

As the map was being created before the companions, all of them were transfixed by the mapmaker’s work—except for Rose. While the others watched the line work magically appearing, she remained focused on the maker.

They had only ever met once before, in this very room, but she had known who he was instantly.

She knew because her mother and grandfather had told her stories about him and about her father, who was called Madoc before he took the name Mordred, and through the stories she came to know them. She knew everything about them, including— or perhaps especially—the flaws that had made them who they became. And she learned something else: that when you know everything about a person, it becomes very difficult to hate them, and very easy to love them.

And so there, in that small stone room near the top of a floating tower made of time, six personages watched the old mapmaker create his work on his living canvas. Two, the clockwork owl and the ancient knight, watched with a sense of duty for what was to come. Three, the Caretakers, watched with awe, reverence, and a small inkling of fear for what the map portended. But only one, the Grail Child Rose, watched with love—because she was the only one there who was more concerned with seeing the mapmaker himself than with obtaining what he might provide to them.

The Cartographer halted to consider his work, then again leaned close and completed the circlet of islands that ringed Charles’s back. “Now,” he said softly, “for the final three.”

He dipped the quill one last time, then stoppered the bottle. “Waste not, et cetera,” he breathed to no one in particular. Swiftly he drew one final island in the center and added several notations above and below.

The old man leaned back and closed one eye, examining, appraising. Then, with a nod that indicated he was satisfied, he stood up and replaced the quill and bottle where he’d found them.

“One of my better works, all told,” he said, wiping his hands on a cloth. “You’re quite a good canvas, young Charles. Patient, not fidgety, very few moles to work around. If I’d had a hundred of you I could have done the entire

Geographica

on the backs of scholars and done away with the parchment altogether. We could have kept you in a village somewhere, growing fat and happy on tea and cakes. Then, whenever a captain needed to go somewhere, we’d just call out your particular island and send you off with him.”

“An interesting idea,” John said as Charles groaned and straightened up. “But what happens when you lose one of the, uh, maps?”

“Interesting doesn’t always equal practical,” came the reply, “but being practical is always less interesting.”

“How do you feel, Charles?” Jack asked as he helped his friend slip his shirt back on. “Does it itch?”

“It’s not really too bad,” said Charles as he tucked his shirt into his trousers. “It does tingle a bit, but not unpleasantly so. A little like having some friendly ants roaming around searching for a picnic.”

“Better you than me,” said John. “When you get back to London, you’ll just have to remember to sleep on your back to avoid explaining it to your wife.”

“No worries there,” said the Cartographer. “The map isn’t visible in the Summer Country—only here, in the Archipelago.”

“Well, if I’d known

that

,” Jack huffed, “I’d have volunteered myself.”

“Mmm-hmm,” Charles hummed skeptically. “I’m sure you would have, Jack.”

“Thank you, for . . . for everything,” said John, offering his hand to the Cartographer, who paused, then took it at the wrist, in the old fashion. “We should leave. There’s no, ah, time to waste.”

“We’ve overlooked one thing,” Jack said mildly. “We’re still stuck in the Keep of Time.”

“It gets easier after the first thousand years or so,” said the Cartographer.

“That is a problem,” John agreed, realizing they’d come via a one-way passage. “And we don’t have a Compass Rose with which to contact anyone either.”

“Isolation clears the mind and sharpens the senses,” said the Cartographer.

“Perhaps we could fashion some sort of rope and lower ourselves down,” Charles suggested.

“And then what?” said Jack. “We swim to the Nameless Isles?”

“We could use the Opening to access the Underneath, and the islands below,” John suggested, rubbing his chin. “Autunno is the closest source of allies we have.”

“That just creates a whirlpool,” Jack countered. “We’d only drop

farther”

“Why are they arguing about this?” Quixote asked the Cartographer. “Aren’t we just going to take the boat?”

The Cartographer shrugged. “I think it’s the process they have to go through. They are somehow required to argue pointlessly about things that are completely irrelevant before deciding to do what was staring them in the face all along.”

John looked at the old men. “You have a boat?”

“Of course I have a boat,” the Cartographer shot back. “You yourselves sent me here in it. It hasn’t gone anywhere else since.” He jerked a thumb over his shoulder at the chaotic shelves behind his chair.

Sitting there on the edge of the uppermost shelf was a small glass bottle that contained a miniature Dragonship.

“The

Scarlet Dragon,”

John said in realization. “I’ve never given it another thought.”

“I’m not surprised in the least,” Archimedes said, preening.

“So it turns into a boat when we break the glass,” Jack said. “We still have no way to escape the tower.”

“I’m suddenly beginning to see why you’re professors,” said the Cartographer as he handed Jack the ship in the bottle. “Arguing about the problem instead of asking if anyone has a solution is the best way to ensure tenure. Cambridge is lucky to have you.”

“I teach at Oxford,” said Jack.

“That’s right,” the old mapmaker murmured. “I keep forgetting what year it is.”

He rustled around in the far corner of the room, where things seemed to be organized in piles rather than piled on shelves. After a minute he uttered a triumphant “Aha!” and turned back to the companions with a wry gleam in his eyes. He was clasping several sheets of parchment as if they were fragile china dolls.

“Here,” the Cartographer said, proffering the pages to John. “See what you can make of these.”

The old sheets of parchment looked very much like those in the

Imaginarium Geographica,

and John said as much, wondering aloud if they might have come from the same milling.

“Identical, in point of fact,” the old mapmaker said with a hint of derision in his voice. “I’m surprised you even questioned it.”

John and Jack examined the pages, which were ragged along one edge. “Torn out?” Jack asked. “Were these removed on purpose?”

The Cartographer nodded. “There are secrets hidden within those pages that were too much to handle for some of the Caretakers-in-training,” he said blithely. “De Bergerac in particular made unorthodox use of them, and when that idiot Houdini was recruited, the Far Traveler and I were vindicated in our decision to tear them out.”

“I thought the

Geographica

couldn’t be destroyed,” said Charles. “Wasn’t that actually a problem when we started all this?”

The Cartographer sighed like a schoolmarm with a worn-out dunce cap. “For one thing, boy, I am the Cartographer. I made the atlas. So I can take out whatever I wish. And for another thing, I wasn’t destroying them, merely hiding them. The ones that have been drawn on are dangerous enough—but four or five centuries ago a rogue Caretaker actually stole a stack of blank sheets.”

“Is this the moon?” John asked, looking through the pages.

“And . . . Mars?”

“Don’t get distracted from your goals,” the Cartographer said, grabbing the pages and riffling through them. “This here is what you need right now.”

The page bore an unfinished drawing of a familiar place that was as comforting in its own way as Ransom’s card of the keep had been.

“That’s home!” Rose exclaimed. “I would so love to go there, Uncle John!”

“Avalon,” said John, nodding. “That would be the perfect place to start the journey to the Nameless Isles. But,” he continued, “the drawing is incomplete. Will it still work in the same way as Ransom’s card?”

“What Ransom does by practice and instinct, you’ll have to do paint-by-numbers,” the Cartographer replied in a tone that was only slightly condescending. “I’ve seen you draw, Caretaker. You should be able to finish what Roger Bacon started.”

“If you have the means to travel out of this place,” remarked Charles, “then why didn’t you leave ages ago? Why don’t you come with us now?”

The Cartographer hesitated, and a hard look crossed his features, then softened. “I am bound, if you’ll remember, to stay here in Solitude, until such time as Arthur chooses to release me.”

“Arthur is dead,” Charles said bluntly.

“Charles,” chided Jack. “His heirs are able to open the door,” he said, turning to the old mapmaker. “I’m sure it is within their power to free you as well.”

“When and if they choose,” the Cartographer said. He clapped his hands together. “But that is a discussion for a different day. For now, you need to finish the drawing and be on your way.”

He provided a pencil and several crayons to John, who quickly began to draw on the sheet, sketching in details of the ruins that existed there now, blurring out the unblemished portrait that Bacon had begun of the structures that were new and unfallen. John had seen the island in both states—pristine and ruined— and he didn’t want to take the risk that a drawing of Avalon as it once was would take them further back in time. Better that it take them to the place as he knew it best, even if it was only a shadow of its former glory.

In less than an hour the drawing was completed.

“Simply use it in the same way Ransom used the Trump,” the Cartographer instructed them. “Hold the picture in your mind, then merge what you see there with the picture before you. It will expand, and you should then be able to step through.

“I would prefer not to watch, if you don’t mind,” he said dismissively. “You’ve distracted me enough today as it is, and I really must get back to work.”

The Caretakers each thanked him and bade him good-bye. Don Quixote gave him a stiff and formal bow, which they were surprised to see returned. Rose gave the old mapmaker a hug, then kissed him on the cheek.

“Thank you, Uncle Merlin,” she said. “I’m sure we’ll see each other again very soon.”

“Yes, yes,” he said, pressing her away. “Be about your business. I must return to mine.”

He turned away from the companions and took up his quill, then began to sketch on the parchment at his desk as if they weren’t even in the room.

“Well enough,” said John. “Let’s take another trip, shall we?”

As they had done with the Trump of the keep, John held up the parchment so they could all concentrate on it. In seconds the soft susurrations of the breezes of Avalon began to swirl through the picture and into the chamber.

The image began to grow, until it filled the entire wall next to the door. Charles, Jack, and Rose moved through, followed by Archimedes and Quixote. John stepped through last, but only after one final glance at the Cartographer. The old man never looked up or ceased sketching with his quill.

The picture began to shrink rapidly, and in moments, it had vanished altogether.

For the rest of the day, the Cartographer sketched random lines across the parchment, creating the illusion of working, but in reality he was making motions at his desk for their own sake. He continued to do so until the point of his quill snapped, splattering ink across the sheet.

In frustration the old mapmaker crumpled up the page and threw it across the room. His lip quivered, and his eyes welled with moisture. Only a single tear escaped and trailed down his cheek to his chin, dropping to the floor, before he took out another sheet of parchment and a fresh pen and once more began to draw.

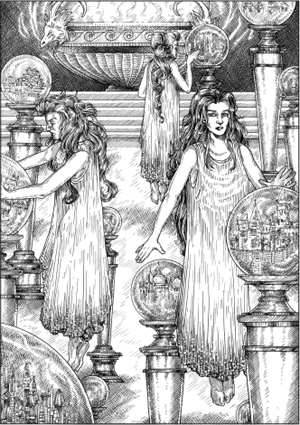

Attending to the various globes were three women . . .

The Grotto

The island

of Avalon occupies an unusual place within the wonder of creation, as it is the only island that exists equally in both the natural world and in that of the Archipelago of Dreams.

As such, it became the first true crossing place between the worlds. In the past there had been other points of passage— usually accidental—but experiments in recent years using dragon feathers and vehicles other than the Dragonships had proven that connections between the worlds are

everywhere.

With the proper preparation, it was possible to cross from any point along the Frontier, the great barrier of storms that protected the Archipelago, into any corresponding point in the natural world.

The steam-powered vehicles called principles had been used on occasion, but most frequently, Bert and other travelers had crossed over in the Dragonships, which Prince Stephen had refashioned into airships. So there was little need to sail on the waters through the traditional crossing point that was Avalon.

A shame,

John thought as he stepped through the parchment,

especially considering the glory that this island once was.

In their journey through the past to rescue Hugo Dyson, John and Jack had been able to see Avalon in its pristine state: alabaster columns supporting high stone arches; glistening temples of marble and mother-of-pearl; walkways and walls of stone inlaid with jade. It was the Golden Age of the gods made manifest in a single ethereal vision. Only the vision was real, as were the goddesses who inhabited it.

“Well,” Charles said once they had all moved through the parchment, “it’s a bit more crumbly around the edges, but otherwise, it actually feels good to see this shabby old island again.”

John chuckled to himself and winked at Jack. Of course Charles would see it differently than they did. He hadn’t been with them on that adventure—not this Charles, at any rate. The “Charles” they’d had with them was from another timeline and was called Chaz. And he made a sacrifice of his own, becoming the first protector of Avalon—the first Green Knight.

“I wonder,” said Charles in what was practically a continuation of John’s thinking, “where the devil that scoundrel Magwich is? Shouldn’t he have appeared by now, waving around a spear and asking us to state our allegiances, or some such?”

“Hmm,” Jack mused, looking around the low embankment. “He’s probably off taking a nap.”

“Well, let’s go,” John began, turning to instruct the others on a plan of action, when he saw Rose and stopped.

She had dropped to her knees in the sand, and her eyes were full of tears. Quixote had knelt beside her and was gently trying to console her. Archie too was doing his best to make supportive gestures.

“We’re all idiots,” muttered Jack under his breath to John. “We were so intent on getting out of the tower that it never occurred to us how she would take coming here.”

He’s right,

John thought as they moved over to the girl,

on both counts.

Rose had been born on Avalon. She was conceived in the city of Alexandria, but her mother, Gwynhfar, had fled the Summer Country and come here. Gwynhfar joined the other two women on the island, the enchantress Circe and the sea-witch Calypso, in becoming the Morgaine—the three supernatural women who may have been the Fates, or goddesses, or simply beings of incomprehensible power.

Sometimes they changed personalities, if not personages— Gwynhfar was not among them when John, Jack, and Charles first met them—but there were always three, and they always reflected aspects of who they truly were. Sometimes they appeared as beautiful women; sometimes, harried old hags. Often the advice they gave was useful, but in John’s experience, they were more manipulative than helpful. But whatever else they were, the original Morgaine had been Rose’s mother and surrogate aunts. And whatever else Avalon represented, it had been the only home she had known, until John and Jack arrived there centuries earlier and took her with them to resurrect a dead king.

From that experience, she went to England and into a boarding school—and she had never come back to the place of her birth until now. So she had no memories of Avalon except from when it was full of gleaming, glorious edifices fit to rival the finest Greek temples. To come here now and see the island in such a state of disrepair had to be shattering.

“What happened?” Rose was asking as the other men knelt beside her. “What happened to my home? How did it get this way?”

“It’s been almost five centuries,” John said softly. “Many things change in that much time.”

“But wasn’t the knight here?” she asked, clutching Charles’s hands. “You were here, Uncle Charles. Why did you let this happen?”

Charles stammered a bit under the directness of the question. “I . . . uh, I wish I could tell you, my dear child,” he said, looking to John and Jack for support. “It wasn’t I who came here, but I know he did the best he could.”

“No one lives forever,” Jack said, nodding in agreement. “Chaz did everything he could, I’m sure—but when he died, another took his place.”

“And another after that,” added John. “There have been twenty-six Green Knights, in fact, and I’m sure they all did the best they could. But nothing lasts forever.”

“Well, something should,” Rose said, still sniffling but calmer now. Quixote produced a beautiful if faded silk handkerchief for her to wipe her face and blow her nose. “Some things should last forever, especially when they exist on an island like Avalon.”

“Tell you what,” said John. “We’ll find the Green Knight, the one who is the Guardian now, and we’ll ask him what happened here.”

“That sounds like a plan to me,” Charles said, rising to his feet and cracking his knuckles. “I’d like to know where Maggot is myself.”

The companions searched the island for the better part of an hour, but to no avail. There was no sign of Magwich.

He’d originally been forced to take the role of protector of Avalon by the Dragons, who offered him the choice of service or slow roasting on a spit. Others had become the Green Knight as a form of penance—but only Magwich, who had been a failed apprentice Caretaker, actually saw the role as a means to do as little as possible. He was lazier than he was stupid, but he was not completely irresponsible. If he was not on the island, then he was either dead, or worse.

“Maggot being dead wouldn’t break my heart,” said Charles with a touch of rancor.

“Whatever else Magwich was,” John reminded him, “he also had Caretaker training. Perhaps not much, but enough to be dangerous. We must find where he’s gone to.”

“But he couldn’t just leave the island, could he?” asked Jack. “Wouldn’t he turn into dust, or at least set off alarms with the Dragons?”

“Artus sent the Dragons away, remember?” John said. “When he set up his republic, and dissolved the monarchy. If they weren’t looking after the welfare of the king, they probably would have cared less about watching the goings-on of a third-rate knight on Avalon.”

As they discussed the Magwich issue, Rose, Archie, and Quixote rejoined them from the short walk they’d taken to the western side of the island. Rose used to spend time there fishing with her paternal grandfather—or at least, that was who John and Jack had assumed the old man was—and she wanted to see if he, at least, was still there.

The expression on her face gave them the answer. Rose was still visibly upset, but she seemed to have mostly regained control of her emotions, and she was back to her usual mode of absorbing the information around her.

Rose was unusual in many ways—this had always been evident. But John realized that today was the first time in a long time that they perceived her as what she really was: a child, trying to learn the lessons she needed to become an adult. And finding that some lessons are harder than others.

“Let’s go look around the cottages and the cave,” Jack suggested. “He’s going to be there, if anywhere.”

“He’s supposed to be here, among the temples,” Charles countered.

“That’s what I mean,” said Jack. “This

is

Magwich, after all. We’ve just wasted time looking for him where he’s supposed to be.”

“Good point,” said Charles.

The narrow path along the western edge was a bit difficult to traverse for Quixote, and the crosswinds were strong enough that Archimedes stayed well inland. But the companions made quick enough time that they arrived in the clearing where the Morgaine lived while the sun was still high above the horizon.

It was a scene of greater entropy than the temple had been. Where three cottages had once stood, there was only scattered rubble and straw. Nothing remained of the cooking pit, and even the old well had been all but destroyed.

Worse still, all the rare and dangerous artifacts that had also been left there for safekeeping were also missing.

“Pandora’s Kettle,” said Charles. “It’s gone!”

“And the shield of Perseus,” Jack added. “And the wands, and armor, and jewels . . . all of it.”

“Damn his eyes,” said Charles. “Magwich was supposed to guard everything on this island. When I find him . . .” He didn’t need to finish the sentence.

“When was the last time we actually saw him here?” John asked. “I can’t really recall.”

“Whenever it was,” said Charles, ”remember we’re missing seven years. A lot of things may have happened in that time alone.”

John nodded in agreement. “The Cartographer said as much. If so many things are going poorly in both worlds, it stands to reason that Avalon would be involved.”

“It’s the fact that the kettle is gone that worries me,” Jack noted, “as well as the only means of capping it—Perseus’s shield. Either Artus and Aven took it to Paralon for safekeeping, or else someone else came to get it—to use it. Only a handful of people ever knew what it could do.”

John’s eyes flicked over to Rose, who was looking down the well and not listening in on the discussion.

“And one in particular who

did

use it,” said John, his voice low, “but he’s dead.”

“His Shadow is still out there somewhere,” Charles reminded them, “and the Trolls and Goblins also knew how the kettle was used. The field of suspects is wide open.”

“Shall we check the cave?” Quixote asked, peering into the dark cavern. On entering the clearing, he had ignored the cottages altogether in favor of the cave, which seemed to have completely entranced him.

“He’s not going to be there,” said Charles dismissively. “He never liked it in there to begin with, and after the Morgaine left, I doubt he had any reason to go in at all.”

“Where did they go?” asked Rose, obviously crestfallen. She was hoping that some aspect of her memories had survived on the island, but it was becoming more and more clear that the place was completely abandoned.

“I don’t know where they went,” Charles said. “After the, ah, accident that caused all the trouble at the keep where your Uncle Merlin resides, the Morgaine told us we had unraveled time itself—and we thought we had put things right, but the next time we came here, they were gone. No one knows where.”

“Most intriguing,” said Quixote. “And no one in the castle could tell you where they went?”

Charles looked at John, then Jack in confusion. “You mean on Paralon?” he said. “No, no one there had any clue, not even Samaranth.”

The old knight shook his head and pointed into the cave. “Not on Paralon,” he said plaintively. “The

castle.

The castle in the

cave

.”

“We’ve been in there, more than once,” Jack said, grimacing slightly at the hint of condescension he heard in his own voice, “and there’s nothing in there but dust and cobwebs. Hasn’t been for over a decade.”

“Pardon,” said Quixote, bowing slightly. If he’d taken offense at Jack’s tone, it didn’t show. “I would not presume to teach such esteemed scholars as yourselves, but I have a special knowledge of this cave. You see, I have been in it before. There is a wondrous meadow there, and a great castle made of crystal. Inside the castle there are wondrous halls of alabaster marble, where the great heroes of history are interred. It is my hope to one day rest among them.

“And,” he said in conclusion, “in that place, sometimes, it is possible to commune with the dead. So if we choose to enter, it may very well be there that we shall find the answers you seek.”

John blinked, then blinked again. “I’m sure we don’t know what you’re talking about, my good knight.”

Quixote sighed, then smiled knowingly. “I am well used to those around me not believing the stories I tell,” he said, gesturing broadly with his hands. “My tales of the adventures in the Archipelago saw me painted with the brush of a teller of falsehoods, never mind that to tell a lie would be ignoble of a knight. So I understand and I tell you with no rancor that it was prophesied that I would sleep until the call came to serve once more. And I believe that I was destined to be here, now, to aid you on your quest.”

John pondered the knight’s words silently for a moment. In the keep, he had told them that he possessed special knowledge that would be needed by them on their journey. None of them had really believed him, and they had taken him with them out of compassion more than anything else. To do otherwise would have meant his death. But they had never actually considered that he might have been sincere all along.