The Silk Road: A New History (32 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

The sea routes continued to grow in importance. Many of those sailing to Chinese ports in the ninth century were Arabs who came from the ports of Iraq, particularly Basra; the trip took around five months.

62

One early description of China written in Arabic dates to 851; the anonymous author gathered testimony from people who had personally visited China.

63

He reports that the Chinese authorities at the port of Guangzhou, the main port of entry for those coming from Iraq, seized the cargo of any foreign merchant, collected a 30 percent tax, and then returned the goods after six months. The Chinese merchants bought ivory, frankincense, cast copper, and tortoise shells, and they paid in bronze coins; in exchange they offered “gold, silver, pearls, silk, and rich stuffs in great abundance,” as well as “an excellent kind of cohesive green clay with which they make cups as fine as phials in which the light of water is seen,” that is, porcelain.

64

Since the authorities required the same travel passes that they did of those entering China overland, all merchants had to report their exact itineraries before they could enter China. The author is remarkably positive about China. He portrays the Chinese legal system as fair, even to foreigners, and he describes the bankruptcy law of the Chinese in great detail.

In 916 a geographer named Abu Zayd copied this account in full and then wrote a sequel to it. Overall, he finds the earlier account accurate, and he mentions a “man of undoubted credit” who helped him make corrections. This informant, he writes, “told us also that since those days [the years before 851] the affairs of China had put on quite another face; and since much is related, to show the reason why the voyages to China are interrupted, and how the country has been ruined, many customs abolished, and the empire divided.” He elaborates: an 877 uprising in Guangzhou, led by a former examination candidate named Huang Chao, led to the deaths “in addition to the Chinese [of] one hundred and twenty thousand people, Muslims, Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians who had sought refuge in the city.”

65

Many doubt the accuracy of this figure: another Arabic source reports that 200,000 perished in Guangzhou, while Chinese sources give no specifics at all.

66

Whatever the exact death toll, the Huang Chao rebels dealt a severe blow to both Guangzhou and the sea trade.

After looting Guangzhou, the rebels arrived in Chang’an early in 881, burned down the Western Market, seized the palace, and sacked the city. Government armies succeeded in driving the rebels out of the city, which they then proceeded to loot themselves. The emperor was reduced to a mere figurehead. The poet Wei Zhuang described the city after the rebels had left:

Chang’an lies in mournful stillness: what does it now contain?

—Ruined markets and desolate streets, in which ears of wheat are sprouting.

Fuel-gatherers have hacked down every flowering plant in the Apricot Gardens,

Builders of barricades have destroyed the willows along the Imperial Canal.

All the gaily-colored chariots with their ornamented wheels are scattered and gone.

Of the stately mansions with their vermilion gates less than half remain.

The Hanyuan Hall is the haunt of foxes and hares.

The approach to the Flower-calyx Belvedere is a mass of brambles and thorns.

All the pomp and magnificence of the older days are buried and passed away;

Only a dreary waste meets the eye; the old familiar objects are no more.

The Inner Treasury is burnt down, its tapestries and embroideries a heap of ashes;

All along the Street of Heaven one treads on the bones of State officials.

67

Chang’an remained the capital for twenty more years, but then in 904 the general who ruled behind the fiction of the Tang dynasty ordered the emperor’s servants killed and the imperial palace dismantled and floated down the Wei River to Luoyang. In 907 he killed the last Tang emperor, seized power outright, and founded a new dynasty. The once-glorious Tang capital lay in ruins, never to recover. The severing of the trade routes to the capital isolated the oases of the northwest, and the Silk Road trade entered a new, quieter era.

CHAPTER 6

The Time Capsule of Silk Road History

The Dunhuang Caves

I

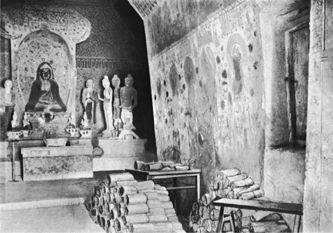

f you are going to visit only one Silk Road site, make it Dunhuang. The physical setting is spectacular. Deep-green poplar and willow trees line the lush oasis. Framed by rocky cliffs, some five hundred caves contain strikingly beautiful Buddhist wall paintings blending motifs from India, Iran, China, and Central Asia. The more than forty thousand scrolls found in the library cave, shown on the next page, form the largest deposit of documents and artifacts discovered anywhere along the Silk Road.

1

The texts of different religions placed in the library cave—Buddhism, Manichaeism, Zoroastrianism, Judaism, and the Christian Church of the East—show just how cosmopolitan this community was. Throughout the first millennium, Dunhuang was an important garrison town, Buddhist pilgrimage center, and trade depot. After the year 1000, though, the city gradually declined into a backwater. In 1907, when Aurel Stein made it the destination of his Second Central Asian Expedition, only a handful of Europeans had visited. His discoveries there secured him both a knighthood in Britain and lasting infamy in China.

On his Second Expedition, Stein drew on his earlier experiences of leading a team through the Taklamakan Desert, excavating documents and artifacts, and publishing them responsibly and promptly. In the six years since the First Expedition to Khotan and Niya, Britain’s rivalry with other nations had intensified; the Russians, Germans, Japanese, and French all had teams exploring and removing antiquities from Xinjiang.

2

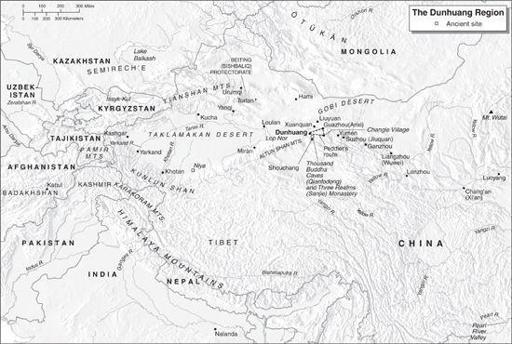

Stein applied for funds so that he could be away for two full years. His goal was to retrace his route from Kashmir to Khotan and then travel through the desert all the way to Dunhuang, on the western edge of Gansu Province, which lay 800 miles (1,325 km) away as the crow flies, 950 miles (1,523 km) by road.

Stein first learned about the Dunhuang caves in 1902, when the Hungarian geologist Lajos Lóczy gave a paper at a congress of Orientalists in Hamburg, Germany. Lóczy had been one of the first Europeans to visit the site in 1879; at the time only two monks lived year-round at the near-deserted site. Although an expert in soil and rocks, Lóczy identified the importance of the Buddhist murals in the caves, which Chinese scholars tended to ignore in favor of scroll paintings.

3

The earliest wall paintings at Dunhuang dated to the fifth century

CE

, much earlier than any surviving painting on silk.

STEIN’S DOCTORED PHOTOGRAPH OF THE LIBRARY CAVE AT DUNHUANG

This photograph shows cave 16, with an image of the Buddha on the central platform, and, on the far right, a small, high doorway to the secret library cave that was sealed sometime after 1000

CE

. Discovered around 1900, the library cave held some forty thousand documents in Chinese, Tibetan, and other lesser-known Silk Road languages, the largest single cache of original documents ever found on the Silk Road. By overlaying two different negatives, Stein later added the two piles of manuscripts to the original photograph of the cave.

The staff of the Second Expedition, like the First, included men to tend the camels and horses, surveyors who could also take photographs, personal servants, and cooks. Also joining the group was a messenger capable of traversing hundreds of miles through the desert without getting lost; his task was to visit nearby towns so that he could retrieve and deliver Stein’s mail and his funding, which the Government of India paid in silver ingots.

Stein’s command of spoken Uighur (the language he called Turki) was useful for work in Xinjiang, but not in Gansu, where Chinese was the dominant language. Dunhuang first came under Chinese rule in 111

BCE

, when the Han dynasty established a garrison at Dunhuang after a successful military campaign. (The Xuanquan post station was part of Dunhuang.) The Chinese controlled the region off and on until 589

CE

, when the Sui dynasty reunified China. From that point on Dunhuang was continuously under Chinese rule.

4

At this regional center of learning, the local people studied Chinese characters in school and wrote in Chinese.

5

On the recommendation of the British consul at Kashgar, Stein hired a Chinese secretary, Jiang Xiaowan. Jiang could not speak Uighur, and communication was initially difficult. Stein never learned to read Chinese, but, after the two men had traveled together for a few weeks, Stein picked up enough spoken Chinese to make himself understood.

As Stein made his way toward Dunhuang in the spring of 1907 he heard a rumor, first from a Muslim trader on the run from creditors, that the caves held much more than wall paintings. The trader told him about the discoveries of a former soldier named Wang Yuanlu, who had come to Dunhuang in 1899 or 1900 after leaving the Qing army. Like many soldiers, he had been converted to Daoism by a wandering teacher, and so Stein called him “Daoist Wang.” He was barely literate. Soon after Daoist Wang’s arrival at the site, he knocked on a cave wall, heard that it was hollow, and discovered the library cave (cave 17) behind it.

6

After dismantling the wall, Daoist Wang presented a few individual scrolls to local and provincial officials, and at least one of these officials, a scholar of ancient Chinese script named Ye Changchi, grasped their importance. Yet, severely pressed for funds in the years after the Boxer Rebellion, the authorities decided not to remove the documents, ordering that they remain in the cave under Daoist Wang’s care.

When Stein and his secretary Jiang first visited the site in March, 1907, Daoist Wang was away “on a begging tour with his acolytes.” They took the opportunity to wander around the cliffside caves, which were open to the elements and entirely unguarded. Stein noted the accuracy of a tenth-century description:

In this valley there is a vast number of old Buddhist temples and priests’ quarters; there are also some huge bells. At both ends of the valley north and south, stand temples to the Rulers of the Heavens, and a number of shrines to other gods; the walls are painted with pictures of the Tibetan kings and their retinues. The whole of the western face of the cliff for a distance of two

li

[two-thirds of a mile, or one km], north and south, has been hewn and chiselled out into a number of lofty and spacious sand caves containing images and paintings of Buddha. Reckoning cave by cave, the amount of money lavished on them must have been enormous. In front of them pavilions have been erected in several tiers, one above another. Some of the temples contain colossal images rising to a height of 160 feet [49 m], and the number of smaller shrines is past counting. All are connected with one another by galleries, convenient for the purpose of ceremonial rounds as well as casual sightseeing.

7