Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (27 page)

- "the slap, slap of Gran’s carpet slippers” (Emily Carr)

- "the clattering of the clogs” in Coketown (Dickens)

- "the loose tripping” feet of the Moroccans (Hans Ganz)

- "the violent clatter of … hobnailed wooden-soled shoes on the school flagstones” of a French provincial town (Alain-Fournier)

- "the flat, soft steps of the barefooted” (W. O. Mitchell)

- "the impish echoes of … footsteps” in the cloisters and quadrangles of Oxford (Thomas Hardy)

- or the way “the floor timbers boomed” under the strong rough feet of Beowulf.

By noting the date and place heard for every sound in the index, it is possible to measure historical changes in the world soundscape as well as social reactions to them. Then we can learn, for instance, that Virgil, Cicero and Lucretius did not like the sound of the saw, which was relatively new in their time

(c

. 70 B.C.), but that no one complained of factory noise until a hundred years after the outbreak of the Industrial Revolution (Dickens, Zola).

We can also note interesting proportional changes, for instance, between the number of descriptions of natural as against technological sounds. I am limiting the following observations to a period for which we have several hundred card samples. (It will be a long time before the index can be built up to a point where it may serve as a reliable indicator for all times and places.) Let us compare the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Europe and America. We note that of all sound quotes from nineteeth-century Britain, 48 percent referred to natural sounds, while during the twentieth century, mentions of natural sounds had dropped to 28 percent. Among European authors the same decline is observed over the two centuries: 43 percent has dropped to 20 percent. Interestingly enough, this decline is not observed in North America (and our sample is very large here so that there can be little doubt about it); just over 50 percent of all quotes for both centuries refer to natural sounds. One might assume that North Americans are still closer to the natural environment, or at least have easier access to it than Europeans, for whom it definitely appears to be disappearing.

But the matter is not so simple. Our index does not show any corresponding increase in the perception of technological sounds throughout the same two centuries except for the period of the First World War, where the number increases sharply and then falls again. (The Second World War did not have a similar effect.) In fact, while the number of perceptions of technological sounds remains at the same level in Europe and Britain (about 35 percent of all observations), in America it actually declines!

But we also notice a decline in the number of times quiet and silence are evoked in literary descriptions. Of all descriptions in our file for the decades 1810–30, 19 percent mention quiet or silence; by 1870–90 mentions had dropped to 14 percent, and by 1940–60 to 9 percent. Thus it would appear that while writers are not consciously perceptive of the accumulation of technological sounds, at an unconscious level they are noticing the disappearance of quiet and silence. All this is perfectly consis- ent with the keynote character of technological noise as I have been describing it.

In going through the cards, I am struck by the negative way in which silence is described by modern writers. There are few felicitous descriptions. Here are some of the modifiers employed by the most recent generation of writers: solemn, oppressive, deathlike, numb, weird, awful, gloomy, brooding, eternal, painful, lonely, heavy, despairing, stark, sus-penseful, aching, alarming. The silence evoked by these words is rarely positive. It is not the silence of contentment or fulfillment. It is not the silence toward which this book is modulating.

Classification According to Aesthetic Qualities

Sorting ounds according to their aesthetic qualities is probably the hardest of all types of classification. Sounds affect individuals differently and a single sound will often stimulate such a wide assortment of reactions that the researcher can easily become confused or dispirited. As a result, study of this problem has been thought too subjective to yield meaningful results. Out in the real world, however, aesthetic decisions of great importance for the changing soundscape are constantly being made, often arbitrarily. The Moozak industry does not hesitate to make decisions about what kinds of music the public is most likely to tolerate, nor did the aviation industry consult the public before it entered on the development of the supersonic-boom-producing aircraft. Acoustic engineers have also succeeded in introducing increasing amounts of white noise into modern buildings and have invoked aesthetics in the process, by referring to the results as “acoustic perfume."

n

When such stupid decisions are being made almost daily, can the systematic study of soundscape aesthetics continue to be ignored? If the soundscape researcher is to assist in developing improved acoustic environments for the future, some kinds of tests will have to be developed for the measurement of aesthetic reactions to sounds. At first they should be kept as simple as possible.

Reduced to its simplest form, aesthetics is concerned with the contrast between the beautiful and the ugly, so a good place to begin might be by simply asking people to list their most favorite and least favorite sounds. It would be good to know which sounds were especially pleasing or displeasing to people of different cultures; for such catalogues, which might be called sound romances and sound phobias, would not only be of inestimable value in a consideration of sound symbolism, but could obviously give valuable directives for future soundscape design. Read in conjunction with noise abatement legislation, sound phobias would also give a good impression of whether a given by-law fairly reflected contemporary public opinion concerning undesirable sounds.

One of the sub-projects of the World SoundScape Project has been to offer such a test in as many different countries as possible. We have tried to run the test in two parts. First, the subjects, who were mostly high school or university students, were simply asked to list the five sounds they liked best and the five they disliked most. Next we had them take a short soundwalk around their environment, and when they returned they were asked to repeat the assignment with specific reference to the sounds they had heard during the walk. I wish we had space to print the complete results to some of the tests, for they make a fascinating exercise in imagination and perception. Reducing them to the extent necessary for inclusion here can only be excused on the grounds that the general patterns produced support the hypothesis that different cultural groups have varying attitudes to environmental sounds.

o

A few general observations are in order. First, climate and geography obviously influence likes and dislikes to some considerable extent. We note, for instance, that while in countries which touch the sea, ocean waves are well liked, in an inland country like Switzerland, the sounds of brooks and waterfalls are a much greater favorite. Where tropical storms may blow in suddenly from the sea, strong winds are disliked (New Zealand, Jamaica). It is also clear that reactions to nature are affected by the degree of proximity to the elements. As people move away from open-air living into city environments, their attitudes toward natural sounds become benign. Compare Canada, New Zealand and Jamaica. In the two former countries, the sounds of animals were scarcely ever found to be displeasing. But every one of the Jamaicans interviewed disliked one or more animals or birds—particularly at night. Hooting owls, croaking frogs, toads and lizards were mentioned frequently. Barking dogs and grunting pigs were also strong dislikes. The animal sound most universally liked was the purring of a cat.

While the Jamaicans had no attitude concerning machine sounds, these were strongly disliked in Canada, Switzerland and New Zealand. Jamaicans also approved of aircraft while the other nationalities did not. For all nations except Jamaica traffic noise was especially objectionable. There can be little doubt about this. From the present as well as similar tests we have run with smaller groups of other nationalities, it appears clear that technological sounds are strongly disliked in technologically advanced countries, while they may indeed be liked in parts of the world where they are more novel. I stress this finding because in attempts to confront the contemporary noise pollution problem I have frequently heard politicians and other opponents argue that we represent a minority, citing the case of the mechanic who enjoys a good motor or the pilot who enjoys listening to aircraft. But there can be no doubt that such attitudes form a small minority, at least among young people.

Among other striking cultural differences is the intense fondness of the Swiss for bells, while in other countries they are scarcely mentioned. On the phobia side, the dentist’s drill elicits some mention in all countries except Jamaica (where it is less familar?). But the sound of fingernails or chalk on slate is mentioned as a sound phobia in all countries, a matter to which we will return presently.

This test needs to be followed by others, more detailed. We need to find out with greater precision how and why different groups of people react differently to sounds. To what extent are the differences cultural? To what extent individual? To what extent are sounds perceived at all? The field is open for some intelligent testing on an international scale.

Sound Contexts

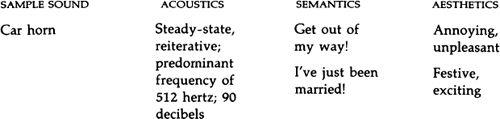

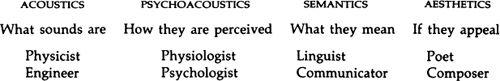

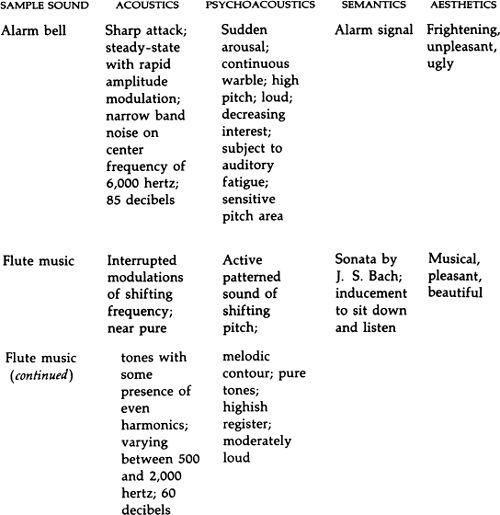

Throughout this chapter sound has been considered in separate compartments. Acoustics and psychoacoustics have been dissociated from semantics and aesthetics. It is traditional to divide the study of sound in this way. The physicist and engineer study acoustics; the psychologist and physiologist study psychoacoustics; the linguist and communications specialist study semantics, while to the poet and composer is left the domain of aesthetics.

But this will not do. Too many misunderstandings and distortions lie along the edges separating these compartments. Interfaces are missing. Let us follow through a few specimen sounds to understand the nature of the problem. Consider first the sample pair of sounds in the following table.

There are apparently no problems here. The two sounds are physically quite different and they accordingly have different meanings and draw forth different aesthetic responses. But even here the context can produce divergent effects. Thus, without altering the physical parameters of the sound, the meaning of the alarm bell could change if, for instance, it was only being tested. Knowing this, the listener would not be impelled to drop everything and run. Or, without changing the physical character of Bach’s flute sonata, the aesthetic effect could be quite different if the listener did not like the flute or did not care for the music of J.S. Bach.

When we get discrepancies such as these, our reliance on automatic across-the-board equations falters, and we become aware of the fallacy that a given sound will invariably produce a given effect. Let us consider some more discrepancies. Two sounds may be identical but have different meanings and aesthetic effects: