Read The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World Online

Authors: R. Murray Schafer

The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment And The Tuning Of The World (28 page)

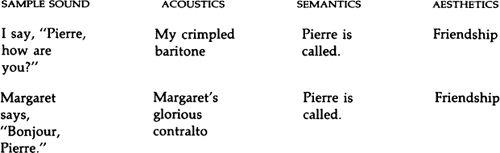

Or two sounds with quite different physical characteristics may have the same meaning and aesthetic effect:

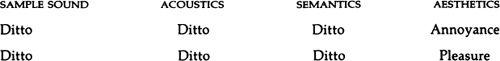

But supposing we are ringing up the Prime Minister of Canada, whose name is also Pierre. Margaret is his wife. I am not. Everything else remains the same, but the aesthetic effect is different:

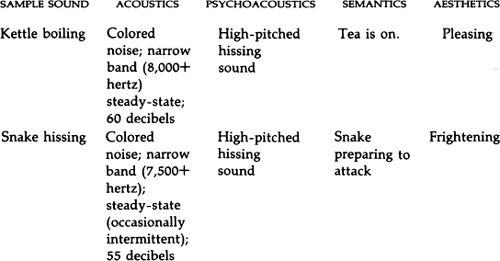

Now consider the following pair of sounds

Here two sounds with similar, but not identical, physical characteristics appear to be identical in perception, but nevertheless cause no confusion in meaning and accordingly have different aesthetic effects. Their contexts keep them clear. But when they are removed from their contexts in tape recordings, they may quickly lose their identities. Nor is the ear acute enough to be able to distinguish whatever differences may exist in their physical structure. Then the kettle may become the snake or either may become a green log on a fire.

It has always surprised me how even quite a common sound can be completely mistaken by listeners, dramatically affecting their attitudes toward it. For instance an electric coffee grinder was described as “hideous,” “frightening,” “menacing” by a group after listening to it on tape, though as soon as it was identified their attitudes immediately mollified.

There is one celebrated sound which seems to epitomize the interface dilemma which I have been describing: the sound of chalk or fingernails on slate. We have shown that it is an international sound phobia. Yet physical analysis fails to reveal why it should send cold shivers up the spine. It is not extraordinarily high or loud. It is not accompanied by any hurtful action. It does not even designate anything in particular. No single discipline then is capable of accounting for its remarkable effect. When sound enigmas like this are explained—and not until then—we will know that the missing interfaces are at last falling into place.

TEN

Perception

It is not surprising, noting the visual bias of modern Western culture, that the psychology of aural perception has been comparatively neglected. Much of the work done has been concerned with binaural hearing and sound localization—which also has largely to do with space. Quite a lot of work has been done on masking (covering one sound by another) and some has been done on auditory fatigue (the effect of prolonged exposure to the same sound); but taken as a whole such researches leave us a long way from our goal, which would be

to determine in what significant ways individuals and societies of various historical eras listen differently

.

Thus it is inconceivable that a music or soundscape historian should get quite the same thrill out of the preparatory work the laboratories have provided as that which has stimulated art historians such as Rudolph Arnheim and E. H. Gombrich, whose work owes such a heavy debt to research in the psychology of visual perception. In the work of men like these it has begun to be possible to comprehend the history of vision, at least in the Western world. The soundscape historian can only speculate tentatively on the nature and causes of perceptual changes in listening habits and hope that psychologist friends may respond to the need for more experimental study.

Figure and Ground

is indeed possible that some terms employed in visual perception may have equivalents in aural perception. At least they are probably worth careful examination. For instance, a phenomenon like irradiation—by which a brightly illuminated area seems to spread—does seem to have an analogy in that a loud sound will appear to be longer than a quiet one of equal duration. It is still not clear whether a term like

closure—

which refers to the perceptual tendency to complete an incomplete pattern by filling in gaps—can be applied to sound with anything like the confidence it has stimulated in visual pattern perception, though experiments in phonology show that for language at least there are striking parallels.

Throughout this book I have been using another notion borrowed from visual perception: figure versus ground. According to the gestalt psychologists, who introduced the distinction, figure is the focus of interest and ground is the setting or context. To this was later added a third term,

field

, meaning the place where the observation takes place. It was the phenomenological psychologists who pointed out that what is perceived as figure or ground is mostly determined by the field and the subject’s relationship to the field.

The general relationship between these three terms and a set I have been employing in this book is now obvious: the figure corresponds to the signal or the soundmark, the ground to the ambient sounds around it—which may often be keynote sounds—and the field to the place where all the sounds occur, the soundscape.

In the visual figure-ground perception test, the figure and ground may be reversed but they cannot both be perceived simultaneously. For instance, looking into the clear water of a pond, one may perceive one’s own reflection or the bottom of the pond, but not both at the same time. If we are to pursue the figure-ground issue in terms of aural perception, we will want to fix the points when an acoustic figure is dropped to become an unperceived ground or when a ground suddenly flips up as a figure—a sound event, a soundmark, a memorable or vital acoustic experience. History is full of such examples and this book is revealing a few of them.

Whether a sound is figure or ground has partly to do with acculturation (trained habits), partly with the individual’s state of mind (mood, interest) and partly with the individual’s relation to the field (native, outsider). It has nothing to do with the physical dimensions of the sound, for I have shown how even very loud sounds, such as those of the Industrial Revolution, remained quite inconspicuous until their social importance began to be questioned. On the other hand, even tiny sounds will be noticed as figures when they are novelties or are perceived by outsiders. Thus Lara notices the noise of the electric lights in Moscow as soon as Pasternak moves her in from the country

(Doctor Zhivago)

or I notice the scraping of the heavy metal chairs on the tile floors of the Paris cafes each time I visit that city as a tourist.

The terms

figure, ground

and

field

provide a framework for organizing experience. As useful as they may be, it would be injudicious to presume that they alone could lead to the goal announced at the beginning of the chapter, for they are themselves the product of one set of cultural and perceptual habits, one in which experience tends to be organized along erspective lines with foreground, background and distant horizon. How accurately they may apply to another society, remote from this one, is the big question we want answered.

Sonological Competence

he psychologist studies the processes of perception; he does not attempt to improve them. But to run his tests he must assume some competence on the part of his subjects. As a teacher of music, my instinct tells me why so little has been accomplished to date. To report one’s impressions of sound one must employ sound; any other method will be spurious. Just as we accused acousticians of playing sound false by turning it into pictures, so we accuse psychologists of playing it false by turning it into stories. This is the limitation of sound-association tests where listeners are asked to describe their impressions of taped sounds in free-association narratives. Whatever the purpose of such tests, it can hardly be to provide a description of perception. The only way to check perceptions is to devise routines by which listeners can reproduce exactly what they hear. This is why the ear training exercises of music are so useful. The dancing of the tongue in onomatopoeic mimesis is another way to check perceptions. As part of the ear cleaning program, I devised many exercises of this sort; for instance, imitate with your voice the sound of a shovel digging into sand, then into gravel, then clay, then snow. This exercise is partly memory work, partly vocal facility. Matching another person’s voice, say in the repetition of a name, is another exercise designed to improve the competence of subjects for acoustic reportage.

In Chapter Two I noted how different languages have special onomatopoeic expressions for familiar animals, birds or insects. Aside from the phonetic limitations of language, the obvious differences in such words

must indicate something

about the manner in which the same sounds are heard variously by separate cultures—or is it that the animals and insects speak dialects?

Impression is only half of perception. The other half is expression. Uniting these is intelligence—accurate knowledge of perceptual observations. With impression we accommodate the information we receive from the environment.

p

Impression draws in and orders; expression moves out and designs. Together these activities, and perhaps some others about which we are as yet less certain, make up what Dr. Otto Laske has called “sonological competence.” Laske points out that sonological competence does not result from the mere reception of sensory information. “If that were so, (psycho)acoustic knowledge would be sufficient for design, but it isn’t. The difference between psychoacoustic knowledge and sonological competence is exactly the difference between a’knowledge of, or about’ and a’knowledge-to-do,’ i.e., between a knowledge of sound properties and a capability for designing.” Laske insists that sonological competence applies to the most rudimentary level of perception, and as such it lies

at

the base of all deliberate attempts at soundscape design.

It is certainly possible that some societies possess better sonological competence than others. The evidence of this book makes it more than an assumption that this was the case when the ear was more important as an information gatherer, and the elaborate earwitness descriptions in works like the Bible and

The Thousand and One Nights

suggest that they were produced by societies in which sonological competence was highly developed. By comparison, the sonological competence of Western peoples today is weak. We have ignored our ears, hence the noise pollution problem. But in addition to our ears and voices we have today an instrument which can be used to assist in reclaiming the abilities of aural discrimination—I mean the tape recorder. With this device sounds can at last be suspended, dissected, intimately investigated. More than that, they can be synthesized and it is in this that the full potentiality of the tape recorder is revealed as an instrument uniting impression, imagination and expression. The tape recorder can synthesize sounds impossible for the voice. Take, for instance, an earthquake. The best description of one I have ever encountered is that of a radio sound effects technician.