The Story of Rome (20 page)

It is also told that when the tale of what Regulus had suffered reached Rome, two noble Carthaginian prisoners were given to his widow and her sons, that they might avenge on these the cruelty done to Regulus.

But these terrible stories of vengeance and torture are now thought by many historians to be untrue.

CHAPTER LV

The Romans Conquer the Gauls

T

HE

first Punic war ended in 242

B

.

C

.

, leaving the Romans in possession of Sicily, while the second Punic war did not begin until twenty-three years later.

For a little time Rome was at peace, and in 235

B

.

C

.

the gates of the temple of Janus were closed for the first time since the reign of the peace-loving King, Numa Pompilius.

But ten years later, the Gauls once again threatened to invade Rome. They were always foes to be dreaded, and some of the old superstitious fears, which had apparently vanished for ever, began once more to spread among the Roman legions.

Omens of ill too were rife. The Capitol was struck with lightning, so the Sibylline books were opened, and behold, it was written, "When the lightning shall strike the Capitol and the temple of Apollo, then, must thou, O Roman, beware of the Gauls."

After that the simplest event seemed to the Romans to forebode evil. And while they brooded over the meaning of a strange light in the sky or a cloud of curious aspect, a large Gallic army was marching through Etruria, upon Clusium, a town only three days' march from Rome. This was the very way their fathers had taken long years before.

When the Consuls were absent from Rome, or already engaged with other matters, prætors were sent to lead the Romans against the foe.

In this case it was a prætor who was sent with a reserve corps to track the enemy. He succeeded in following the Gauls to Clusium, and believed the enemy was in his grasp.

But during the night, the main body of the Gauls slipped quietly out of their camp and marched some distance off, leaving only the cavalry to guard the tents. They hoped to entrap the Romans.

The prætor, finding only a small force of cavalry in the camp, ordered an attack. As the Gallic horse retreated, the Romans followed, to find themselves, almost at once, face to face with the whole force of the barbarians.

A fierce struggle followed, in which six thousand Romans were slain. Those who were left alive entrenched themselves with the prætor on a hill, and were at once surrounded by the Gauls.

Meanwhile Æmilius, one of the Consuls, found himself free to hasten to Clusium with a large army. Here he heard of the disaster that had befallen the arms of Rome, and he resolved to restore her fortune.

The prisoners on the hill were soon cheered to see the watchfires of their comrades, and they were sure that in the morning the Consul would scatter the barbarians.

But the Gauls had no wish to encounter Æmilius while they were laden with prisoners and booty. So they began to march northward, followed by the Consul, who harassed their rear, and wrested what booty he could from the retreating-foe.

Suddenly the barbarians were ordered to halt. Their chiefs had seen another army approaching. If they were Romans, the Gauls saw that they were caught in a trap.

It was indeed a Roman army that was marching toward them, led by Regulus, the son of the Consul who had perished at Carthage. He was on his way to Rome when he unwittingly startled the Gauls by his appearance.

With an army marching straight toward them and another in their rear, there was nothing left for the Gauls to do save prepare for battle.

One part of the Gallic army continued to face northward, ready to destroy, as they hoped, the troops led by Regulus. The other turned to the south, to face Æmilius, who was eager to attack the warriors. A short time before it had seemed as though they were going to escape the punishment he was anxious to inflict.

Those who advanced upon Æmilius were the fiercest of all the fierce Gallic tribes. They wore neither armour nor clothes, but their bodies were covered with ornaments.

The chiefs wore the richest jewels, for they were adorned with heavy collars and bracelets of twisted gold, the sight of which filled the Romans with greed. Their savage war-cries filled them with fear.

Amid the blowing of horns and trumpets, the Gauls, still shouting their wild battle-cries, dashed upon the enemy, while they, remembering the dread day of Allia, fought with all their might.

Toward the north, the battle also raged. Regulus himself led his cavalry, but he was slain almost at once. The barbarians cut off his head, and in their savage way held it aloft on a spear, that his followers might see what had befallen their leader. With no one to command them, the cavalry withdrew, to allow the infantry to advance.

But the Gauls soon found that their weapons were of little use against the shield or helmet of the enemy. Their swords, of which the steel was badly tempered, bent at the first stroke and glanced aside, leaving the Roman's shield or helmet unglazed.

Fierce was the struggle between the two forces, but ere long the barbarians found that the day was going against them. The knowledge made them fight but the more desperately.

Slowly but steadily the Roman legions now began to close in, shutting the Gauls together in their midst, until at length they were hemmed in so relentlessly that it was not possible for them to use their arms. Then the Romans slaughtered them without mercy.

Forty thousand were killed, ten thousand taken prisoners, while one of the Gallic kings was captured alive. The other perished by his own hand.

All the booty that the Gauls had taken from the Romans, when they enticed them out of the camp at Clusium, was now recaptured. The Gauls themselves were robbed of their ornaments and their land was invaded by the victorious armies.

Æmilius then led his troops back to Rome and was given a great triumph, while the people thanked the gods that their city was safe from the barbarians.

For three years the war with the Gauls continued, until, from the Apennines to the Alps, the whole plain of Northern Italy had been subdued and was subject to Rome.

CHAPTER LVI

The Boy Hannibal

T

HE

Carthaginians, as you know, had been turned out of Sicily at the end of the first Punic war. They had, too, lost more than Sicily, and were eager to atone for their losses by gaining territory in other lands.

Their thoughts turned to Spain, where already they had a few colonies.

So while the Romans were busy fighting against the Gauls, and too engrossed with the barbarians to trouble about the ambitions of the Carthaginians, they sent their general Hamilcar Barca to Spain, to add to the power and dominion of Carthage.

This was in time to prove the cause of the second Punic war.

Before setting out for Spain, Hamilcar went to the temple to offer a sacrifice to the supreme god of his people, at the same time beseeching him to grant success to his adventure.

As he turned away from the altar he caught sight of his little son Hannibal, then a boy of nine years old, who was watching his father with eager, awe-struck eyes.

Bidding those who stood near to withdraw, Hamilcar called the boy to him, and asked if he would like to go with him to Spain.

To go with his gallant father! To be a soldier like him!

There was no need for the child to answer, his eager face told his father all he wished to know.

So then the great general solemnly led his little son to the altar and bade him lay his hands upon it, as he swore never to be the friend of the Romans.

Hannibal took the oath as his father bade him, and never, in all the years to come, did he forget it. His hatred of the Romans grew with his strength, and when he became a man, his chief aim was to thwart their plans and overthrow their power. So it happened that when Hamilcar set out for Spain, Hannibal went with him.

In the camp the boy soon learned to love the hardships as well as the joys of a soldier's life.

His father himself saw that he was trained as a good soldier should be. In the end he gave his life to save his son from danger on the battlefield. After his father's death, Hannibal served under his brother-in-law, Hasdrubal, for eight years.

While he was still young, he was given a command in the army, and none was ever loved by his men as was he.

In battle, the young leader was always to be found at the point of danger, and every hardship, in the camp as on the field, he shared with his men. Nothing seemed able to daunt his spirit. In disaster as in success he remained cheerful and confident. And he complained of no trouble when it could help his cause.

Until he was twenty, Hannibal lived his hard and happy soldier life. Then young as he was, a great responsibility was laid upon him.

Hasdrubal was killed in his tent by a slave whose master he had murdered, and the army shouted with one voice, that no one but Hannibal should become their commander.

And at length, the government of Carthage reluctantly agreed that the young soldier should be appointed. Until now this important post had been filled by men of greater age and wider experience than Hannibal.

But the new general soon showed the stuff of which he was made. He was young and energetic, and in two years he had taken many towns and added to the power and possessions of Carthage in Spain.

But Saguntum, a town on the east coast of Spain, defied Hannibal's efforts and remained unconquered. As the inhabitants watched the growing power of the young Carthaginian leader, they grew afraid, lest they in the end should be forced to yield. So they appealed to Rome for help.

In the winter of 220

B

.

C

.

a Roman embassy was therefore sent to Spain, bearing a message from the Senate for Hannibal.

The young leader received it with no goodwill. Did it not come from the country he had sworn to hate, and had not his hatred grown, until now it had become the burning passion of his life ?

But although the Roman ambassadors found Hannibal in no pleasant mood, they did not attempt to pacify him. Haughtily they gave their message that he should not attack Saguntum, or dare to cross the river Ebro, beyond which the Carthaginians had not yet advanced.

Hannibal listened with undisguised disdain to the demands of the Senate, and dismissed the ambassadors from his camp without an answer.

In the spring of 219

B

.

C

.

, it was plain that he went to defy Rome, for he laid siege to Saguntum.

For eight months the city held out. When their provisions failed, and starvation stared them in the face, they still refused to surrender, believing that Rome would send help.

But at length all hope of relief faded. Then the Spanish chiefs determined to die rather than fall into the hands of the enemy. So they ordered a fire to be kindled in the market-place, and into it they flung all the treasures which were left in the city. After the treasures were consumed, they themselves leaped into the flames and were burned to death.

When tidings of the fall of Saguntum reached Rome, she sent an embassy to Carthage, at the head of which was a noble named Fabius.

Fabius demanded that Hannibal and his officers should be given up, otherwise Rome would declare war against Carthage.

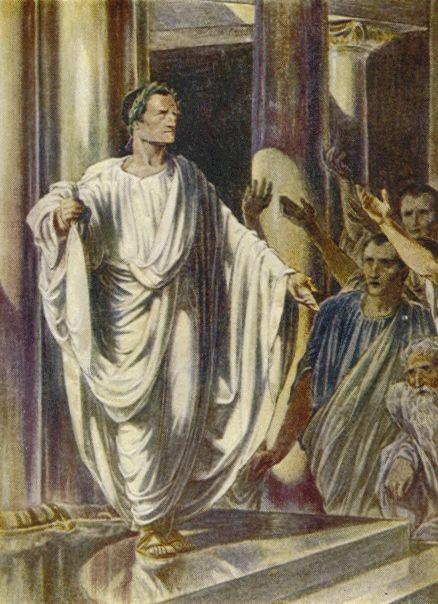

While the Carthaginians hesitated, Fabius rose, and gathering up the folds of his toga, as though in them he held the fate of the city, he cried, "I carry here peace and war. Choose, men of Carthage, which ye will."

"I carry here peace and war, choose men of Carthage, which ye will."

"Give us whatever ye wish," answered the Senate.

Then shaking out the folds of his toga Fabius answered, "Then here I give ye war," and without another word he left the Senate-house.

"With that spirit with which ye give it, shall we wage it," cried the Carthaginians, while the ambassador strode away.

As the shout of the Assembly followed him, Fabius knew that the men of Carthage did not dread his gift.

CHAPTER LVII

Hannibal Prepares to Invade Italy

T

HE

Romans thought it would be an easy matter to send an army to Spain to punish the young general for his daring defiance of the Senate. But as they soon found, it was not so simple as they had deemed.

Hannibal had ambitions beyond the wildest imaginations of the Romans, and before they had sent an army to Spain, he had left the country to invade Italy, for this was his great ambition.

In order to reach Italy, he determined to lead his army across the Alps, a feat that no one without the genius and the daring of the Carthaginian general could have ever hoped to accomplish.

The Gauls, who had so lately been at war with Rome, promised to join Hannibal's forces. When he was assured of the help of the barbarians, Hannibal called his soldiers together and told them his plans.