The Story of Rome (22 page)

Then they turned and fled towards the Trebia, hoping to be able to cross it and to regain their camp. But many of them were cut down before they reached the river, while, of those who attempted to recross the cold and swollen waters, many were drowned.

Only ten thousand in the centre of the Roman army succeeded in keeping their ranks unbroken. These brave soldiers pushed their way through the enemy and retreated to Placentia, a town on the river Po, which had already been taken and fortified by their own legions.

Before the day was over the Carthaginians, too, had suffered severely from the weather. Showers of rain and snow forced them at length to give up the pursuit of the Romans and hasten to their tents for shelter and warmth. Many of the elephants perished in the storm.

When Rome heard of the defeat of her two armies, and that both her Consuls were shut up in Placentia with a remnant of their soldiers, she was dismayed at the greatness of the disaster. Moreover, she was well aware that this victory would make the Gauls cleave more steadfastly than before to the successful general.

Thus the year 218

B

.

C

.

drew to a close, while signs of evil omen added to the anxiety of the citizens of Rome.

Rain fell; no gentle, refreshing showers, but rain of red-hot stones. In the market-place a bull ran up the third story of a house and leapt from thence into the street. And who ever heard of a child of six months old being able to speak! Yet one of just such tender age was heard to shout "Triumph."

Even the least superstitious saw in these strange portents the hand of the gods, and they trembled for what might next befall.

CHAPTER LX

The Battle of Lake Trasimenus

E

ARLY

in 217

B

.

C

.

Hannibal broke up his camp in the valley of the Po.

The Gauls in large numbers were still with him, but he had lost many of his own loyal soldiers, since he had crossed the Rhone a year earlier.

Now, with the first sign of spring, he marched to the river Arno. Here his difficulties began.

The country through which Hannibal wished to take his army was in a state of flood. As the snow melted on the mountains, streams of water poured down into the valley, and these streams, along with the heavy rains of spring, had made the ground like a vast swamp.

Many of the Carthaginians sank deep into the marsh, and they and their beasts perished.

For three days, part of the army was forced to wade through the floods, and, when night fell, there was no dry spot on which to pitch its tents. The soldiers had perforce to rest as well as they could on the bodies of their poor fallen steeds or amid the baggage which had been left behind by their comrades.

Damp and hardships of this kind made many of the soldiers ill, while Hannibal himself lost the sight of one eye, through an attack of inflammation.

But it was the Gauls who suffered most, and they were less willing than the well-trained Carthaginian troops to endure hardship. Had it been possible they would have deserted, but Hannibal, knowing their fickle ways, had ordered his brother Mago with the cavalry to ride at the rear of the army.

As the march continued, it seemed that Hannibal was on his way to Rome. He passed the Roman camp where Flaminius, one of the new Consuls, was in command, and then continued southward, with no army now to hinder his approach to the city.

But what the great general was really trying to do was, not to reach Rome and besiege it, since for that he had not the necessary machines, but to entice the Roman army from its camp and force it to fight. All unwittingly, the army fell into the trap which the Carthaginian set.

Flaminius had been sent into Etruria to see that Hannibal did not march upon Rome. As he had allowed the enemy to pass his camp unhindered, he determined to atone for his error as well as might be, by following swiftly and destroying it.

The Consul was urged to wait until his colleague Servilius joined him, but this he was much too impatient to do.

Hannibal meanwhile had reached the Trasimenus Lake. Between the lake and the mountains ran a narrow road. The general saw at once that this was the very place in which to entrap the Roman army. So he sent his men to command the heights that overlooked the path.

That same evening, Flaminius encamped a short distance from the lake. He could see the narrow road stretching out before him.

Early in the morning the Romans were again on the march, hastening after the enemy that was, as they believed, on the way to Rome.

Unaware of evil, they marched along the narrow road by the side of the lake, scarce able to see a step before them, so heavy hung the mist on the pathway and along the foot of the mountains.

But up on the heights, where Hannibal had posted his men, the sun was shining bright.

The Consul was glad of the mist. He would be able to approach the enemy unseen and attack it suddenly, while it was in marching order and unprepared for battle.

On and on tramped the Roman soldiers, and although they knew it not, they were tramping to destruction.

Hannibal waited until the rearguard had entered the defile, and then he gave his men the signal to attack.

Suddenly the Romans seemed to see the mist break and scatter before their eyes, pierced by the terrible battlecry of the Gauls and by the quick tramp of Hannibal's cavalry as it dashed out of the silence, upon the startled foe.

Javelins and arrows, hurled by unseen hands penetrated the mist as it again closed around them, while great stones came crashing down upon them, too huge to be withstood by shield or helmet.

In vain Flaminius strove to rally his panic-stricken troops. They but rushed the more wildly hither and thither, falling now upon the enemy, now upon each other, in their despair. The Consul himself fought bravely, but he soon fell wounded to death.

Thousands of his soldiers were slain. Some threw themselves into the lake, hoping to swim to safety, but their armour weighed them down and they were drowned. Others waded out as far as they dared into the water, only to be followed by the cavalry of the enemy and slaughtered without mercy.

It was useless to cry for quarter that day, for it was a day of vengeance and of sacrifice to the gods of Carthage. In three short hours, the Roman army was not only defeated; it no longer existed.

Only a body of six thousand men escaped. It had been at the vanguard of the army, and had cut its way through the enemy to the top of the hills.

Here the survivors stayed until the mist lifted, knowing nothing of what had befallen their comrades, until it was too late to go to their aid. So they then entrenched themselves in a village not far from the lake, but Hannibal's cavalry soon surrounded them and forced them to surrender.

In the battle of Lake Trasimenus the Carthaginians lost but fifteen hundred men, and of these the larger number were Gauls.

Fugitives from the army soon reached Rome, and threw the citizens into consternation by the terrible and different tales they told.

The following day tidings of the awful slaughter at the edge of Lake Trasimenus reached the Senate.

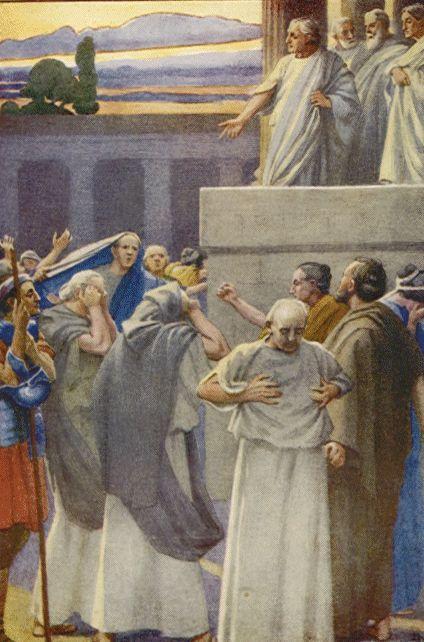

Then the people thronged into the Forum and surrounded the Senate-house, demanding to know what really had happened.

In the evening, when the people's patience was all but at an end, Marcus, one of the prætors, mounted the public platform and cried in a loud voice, "We are beaten, O Romans, in a great battle, our army is destroyed, and Flaminius the Consul is slain."

"We are beaten, O Romans, in a great battle, our army is destroyed."

At the words of Marcus the city became a scene of wild despair. Many men and women who had lost their husbands and sons called down the curses of the gods upon their enemy, others wept and prayed in the temples and forbore to curse, for all the bitterness of their loss.

Amid the tumult, the Senate alone remained calm. Day after day, from early morning until late in the evening, it sat to consider how it might best save the city from the mighty conqueror.

Three days passed, and then even worse tidings arrived.

The Consul Servilius had sent his cavalry to prevent Hannibal's advance on Rome, but it had been either captured or put to the sword. Servilius without his cavalry was powerless to prevent the Punic army from advancing upon the city.

In a short time indeed, Hannibal, at the head of his triumphant army, was scarcely two days' march from Rome.

Flaminius was dead. Between Servilius and the city was the Carthaginian army.

Being bereft of both her Consuls, Rome determined to appoint a Dictator.

CHAPTER LXI

Hannibal Outwits Fabius

T

HE

Senate had restored some sense of confidence to the stricken people by its gravity and calmness. It had also reassured them by destroying the bridges by which the city could be approached and by strengthening her walls.

Soldiers who had been deemed too old to follow the army were now called together, and armed with weapons which had hung for years in the temples—trophies these from many a hard-fought field.

But most important of all, a Dictator was chosen to guide Rome in the crisis that had befallen her.

Fabius, the noble patrician who was elected, was a wise man, and one who was not easily swayed by others. He was, however, neither a brilliant nor an enterprising soldier.

Minucius, one of the people's favourites, was appointed to be the Dictator's master of horse.

Now many of the people believed that disaster had overtaken the army because Flaminius had marched to the war without first offering sacrifices to the gods. And also because he had treated their warnings with contempt.

For as he rode off to join his troops he was thrown from his horse, while a standard that had been thrust into the ground was found to be so firmly embedded that the standard-bearer, with all his efforts, could not dislodge it. These omens Flaminius had treated with scorn, merely remounting his steed and ordering the standard to be dug out of the ground.

Fabius the Dictator, therefore, determined before he did aught else, to pacify the anger of the gods and at the same time to please the people.

So he ordered white oxen to be offered in the temples, as an atonement for the neglect shown to the gods by Flaminius. The people flocked gladly to these sacrifices, bringing with them their own offerings to lay on the altars, while they prayed for the goodwill of the god of battle.

A vow, too, was made by the whole of the people, to keep "A holy spring."

This vow said that "every animal fit for sacrifice, born in the spring of the year 216

B

.

C

.

, and reared on any mountain or plain or river bank or upland pasture throughout Italy, should be offered to Jupiter."

There was no need to offer children to the gods in sacrifice, for they, when they grew old enough, offered their lives, and that right willingly, on the battlefield to the god of war.

When the religious rites were ended, Fabius prepared to meet the enemy.

Two new legions were soon raised, and Servilius was ordered to bring his two legions to Rome, so that Fabius had four legions to lead to battle.

The Dictator had his own idea of how best to beat Hannibal, and to this idea he remained faithful, although his own followers as well as the enemy derided his policy.

Fabius had determined not to meet the Carthaginians in a pitched battle. They had already been victorious too often in such a struggle. He intended to harass the rear guard of the enemy and to cut off the parties Hannibal sent out in search of food or forage. This discreet policy proved pleasing neither to Hannibal nor to his own troops, but of this Fabius recked little.

After deciding on these tactics, the Dictator led his legions into Northern Apulia and encamped near to the enemy. In vain Hannibal tried to tempt Fabius to fight. He wantonly burned the homesteads and destroyed the vineyards of the Italians, that the Dictator might grow indignant and hasten to their help. But seemingly untouched by the desolation of his country, Fabius continued to follow his own method of warfare.

This method of delay has since his time become a byword, and is known as "The Fabian Policy." He himself was named, or perhaps I should say he was nicknamed, Cunctator, The Delayer.

Minucius, the master of the horse, eager for battle, encouraged the soldiers in their discontent with the Dictator, until they even dared to say that Minucius was more fit to command Romans than Fabius.

Then Minucius, seeing the men were in his favour, grew more daring, and ventured to jest at the Dictator because he encamped always on the hills, while the enemy was in the plains. "It is," said the officer, "as if Fabius has taken us to the hills as to a theatre, to look at the flames and desolation of our country." Or he would mockingly declare that the Dictator was leading them up to heaven, having no hopes on earth, or even that he was trying to hide them in the clouds from the Carthaginians.