The Success and Failure of Picasso (9 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

Ortega y Gasset is the last of the classically reactionary thinkers; he cannot, like all the dons who still apologize for capitalism and who pretend that imperialism doesn’t exist, be dismissed as an opportunist. He has been preserved in Spain as in amber, and he is acute and imaginative enough to be obsessed by the historical situation in which he finds himself. All his books are about the historical rack. I think of him because he invented a phrase which is so apt for Picasso. He is generalizing about the modern European masses. On to them he projects all his aristocratic fears of the underprivileged and uneducated. He uses the word primitive in a pejorative sense. But in the case of a truly imaginative writer, images can transcend conclusions. This is what he writes:

The European who is beginning to predominate … must then be, in relation to the complex civilization into which he has been born, a primitive man, a barbarian appearing on the stage through the trap-door, a vertical invader.

7

Picasso was a vertical invader. He came up from Spain through the trap-door of Barcelona on to the stage of Europe. At first he was repulsed. Quite quickly he gained a bridgehead. Finally he became a conqueror. But always, I am convinced, he has remained conscious of being a vertical invader, always he has subjected what he has seen around him to a comparison with what he brought with him from his own country, from the past.

I do not want to suggest that Picasso is naïve, that he was a kind of sublime but helpless farm boy like the Russian poet Yessenin (who also was a kind of prodigy). Picasso was shrewd and even cunning. He soon had the measure of the society he found himself in. And in his case there is less evidence than with any of his contemporaries, who suffered in the same way, that he was fundamentally changed or damaged by the first years of poverty and neglect. The fact that he was a vertical invader from the past was not, in any obvious way, a handicap, and it soon appeared to be an

advantage. What it gave him were special standards with which to criticize what he saw.

Picasso never doubted that he had to stay in Paris. He needed Paris. He needed the example of other painters, the friends he could find there, the chance of success which it offered, its sense of modernity, its European scale. He had no illusions about Spain. He recognized that as a painter in Spain he had to deal with the middle classes and he was aware of their imprisoning provincialism. He was fully aware that Paris represented progress, and that he had his own contribution to make to that progress.

Yet at the same time this progress, as he found it working itself out in reality, horrified him. It took away with one hand what it gave with the other. Poverty is not surprising to any Spaniard. But the poverty Picasso witnessed in Paris was of a different kind. In the Paris self-portrait of 1901 we see the face of a man who not only is cold and hasn’t eaten much, but who is also silent and to whom nobody talks. Nor is this loneliness just a question of being a foreigner. It is fundamental to the

poverty of outcasts in a modern city. It is the subjective feeling in the victim that corresponds exactly to the objective and absolute ruthlessness that surrounds him. This is not poverty as a result of primitive conditions. This is poverty as the result of man-made laws: poverty which, legally accepted, must be dismissed from the mind as unworthy of any consideration.

8

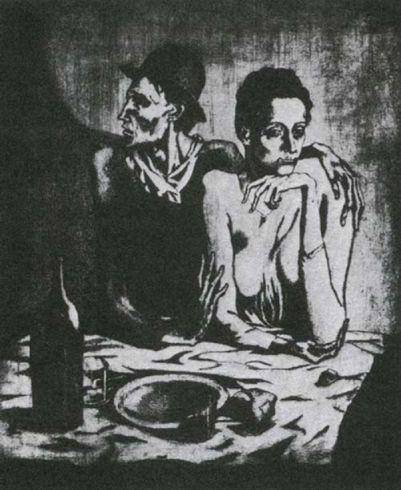

Many peasants in Andalusia must have been hungrier than the couple at table in the etching of

The Frugal Meal.

18

Picasso. Self-Portrait. 1901

19

Picasso. The Frugal Meal. 1904

But no couple would have been so demoralized, no couple would have felt themselves to be so worthless. Here is an extract from an anarchist pamphlet published in Andalusia at about the same time as this etching was made in Paris:

On this planet there exist infinite accumulations of riches which, without any monopoly, are enough to assure the happiness of all human beings. We all of us have the right to well-being, and when Anarchy comes in, we shall every one of us take from the common store whatever we need: men, without distinction, will be happy: love will be the only law in social relations.

9

The couple at the table have left such naïve hopes far behind. They would laugh outright at such innocence. But by this advance (for the anarchist hopes

are

unrealistic) what have they gained? What has their wider knowledge and experience brought them? A profound contempt for reality and hope, for others, and for themselves. Their only value, as Picasso sees them according to the logic of the European city, is that they represent the antithesis of the well-fed. They do not claim any rights. They scarcely claim humanity. They claim only disease with which to shame health, vulgarized and monopolized by the bourgeoisie. It is a terrible advance.

This is not of course the only logic of a European city. Picasso’s view is one-sided, and this helps to explain the sentimentality of much of his work at this time – such exaggerated hopelessness borders on self-pity. (It is also why, much later, paintings of this period became so popular with the rich. The rich like to think only of the lonely poor: it makes their own loneliness seem less abnormal: and it makes the spectre of the organized, collective poor seem less possible.)

Yet Picasso’s attitude is understandable enough. His politics were very simple. It was among the outcasts, the

Lumpenproletariat

, that he lived. Their misery was of a kind he had never before imagined. Probably, he was also suffering from venereal disease and was obsessed by it. In many of his pictures at this time he dealt with the theme of blindness. Critics point out that he must have seen many blind beggars in Spain, but I believe the significance of the subject was deeper and more personal: Picasso feared blindness as a result of his disease. He imagined this disease destroying the very centre of him, and this subjective vision corresponded with the real examples of socially induced self-destruction which he saw all around him.

Quite quickly – and it may have been connected with an improvement in his health – Picasso became more defiant. He still painted outcasts and still identified himself with them, but they were no longer hopeless victims. They now had skills and a tradition of their own. They became acrobats or clowns and their way of life was nomadic and independent.

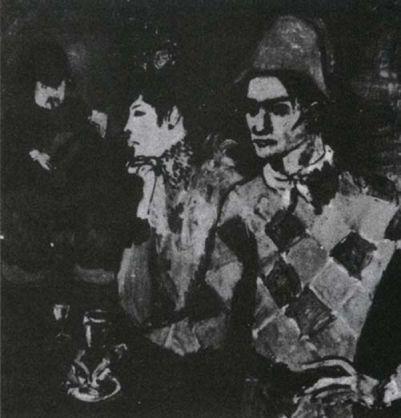

20

Picasso. Clown with a Glass (self-portrait). 1905

21

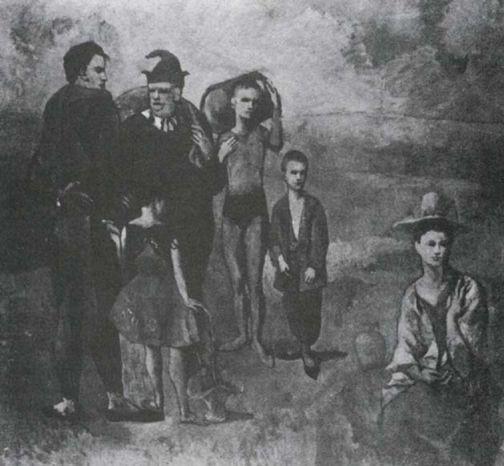

Picasso. Family of Saltimbanques. 1905

It becomes highly questionable whether these men and women would ever agree to become members of modern European society. They may be underfed and scantily dressed, but they have kept their distance and self-respect, and the grace of their skills is a token of a purity of spirit unattainable in a modern city. They are primitives in the sense that they are nearer to nature. They may be sad, but they know nothing of

legalized

suffering.

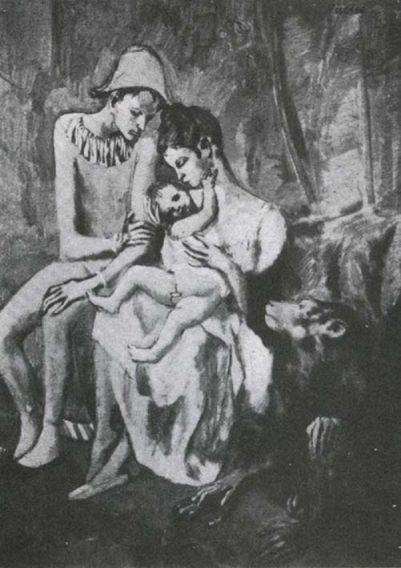

As if to emphasize this point of their nearness to nature, of their familiarity with natural as opposed to man-made law, Picasso often includes animals in these paintings, but animals with whom the figures have a special understanding. A boy leads a horse. Others ride horses bare-back. A dog nuzzles against a leg. A goat follows a girl. An ape sits beside a woman like a brother to the child on her lap.

22

Picasso. Acrobat’s Family with Ape. 1905

Perhaps I should make it clear that I am not now concerned with judging these pictures – though personally I find them over-nostalgic and mannered. Nor need we be concerned with the stylistic problems which most writers about Picasso set themselves. Why during the Blue Period did Picasso paint in blue? And why did he paint in pink in 1906? The answers may be interesting, but there is a grave danger of not seeing the wood for the trees.

If we are concerned with the spirit of Picasso which appears to dominate all else, then the following is what is essential for our purpose: Picasso recognized that he had to come to

Paris because he knew that he had no professional future in Spain; in Paris he came face to face with the misery of a modern European city – a misery which combines brute suffering with delirium; he reacted against this by idealizing simpler, more primitive ways of life.

So far, it might seem that his coming to Paris was of doubtful value. Might it not have been more logical to reject the whole idea of being a

professional

painter and leave Europe, as Gauguin had done fifteen years earlier, for the South Seas?

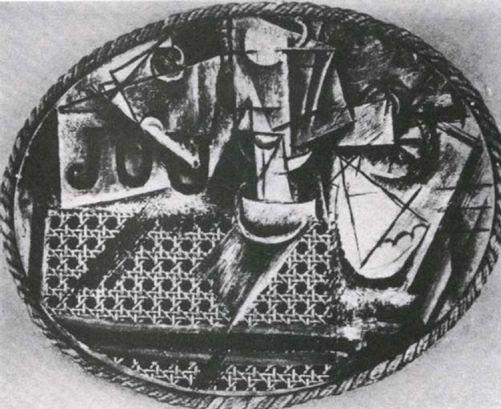

The value of Picasso being in Paris is proved by what happened from 1907 onwards. Earlier, he had already begun to make friends with French painters and poets – particularly with

Max Jacob and Guillaume Apollinaire. In 1907 he met Braque. What happened from then onwards is the history of Cubism. Cubism as a style was created by painters, but its spirit and confidence were maintained by poets. From 1907 to 1914 Cubism transformed Picasso – that is to say Paris and Europe transformed him. Perhaps transformed is too strong a word: Cubism gave Picasso the possibility of going outside himself, of giving his nostalgia the means to become a passionate plea, not for the past, but for the future. And this is true despite the fact that Picasso was one of the creators of Cubism. I have already said that Picasso’s Cubist period was the great exception of his life. If we are to understand how this ‘exception’ came about, and how Cubism transformed Picasso, we must now examine the historical basis of the Cubist movement.