The Success and Failure of Picasso (12 page)

Read The Success and Failure of Picasso Online

Authors: John Berger

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Artists; Architects; Photographers

Parallel with this development there had been a period of rapid colonial expansion. Between 1884 and 1900 the European powers added one hundred and fifty million subjects and ten million square miles to their empires. By 1900 they had reached the stage where, for the first time,

there was nothing left to claim – except by claiming from one another. The whole world was owned.

Today we cannot forget or ignore what all this was leading to. We see the First World War, Nazism, the Second World War, the struggles for independence from imperialism, the millions of dead: starved, burnt or dismembered. We can also see the increasing anonymity of life as the scale grew larger and larger: the anonymity of death by the electric chair (first authorized in 1888), of the skyscraper, of government decisions, of the threat of nuclear war. Kafka, whose formative years were 1900 to 1914, was the prophet of this anonymity. Other artists of the same period – Munch and the German Expressionists – sensed the same thing, but only Kafka understood the full horror of the new bargain: the bargain by which in exchange for sustenance a man forgoes the right to have his existence noticed. No god invented by man has ever had the power to exact such punishment.

Yet this is only one half of the truth: the enormous and most dramatic truth in whose unfolding and realization we, born in the first half of the twentieth century, are participating. Imperialism and monopoly capitalism also represented a promise. By 1900 or 1905 the scale of both our fears and hopes were fixed, though nobody at the time fully realized it.

Monopoly capitalism was the highest, most developed form of economic organization yet achieved by man. It involved planning on an unprecedented scale, and it suggested the possibility of treating the whole world as a single unit. It brought men to the point where they could actually see the means of creating a world of material equality. This point is the opposite pole from where the old anarchist stands looking down at Malaga.

Lenin was the first to see the new developments in this light. In 1916 in

Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism

he wrote as follows:

When a big enterprise assumes gigantic proportions, and, on the basis of exact computation of mass data, organizes according to plan the supply of primary raw materials to the extent of two thirds or three quarters of all that is necessary for tens of millions of people; when the raw materials are transported to the most suitable place of production, sometimes

hundreds or thousands of miles away, in a systematic and organized manner; when a single centre directs all the successive stages of work right up to the manufacture of numerous varieties of finished articles; when these products are distributed according to a single plan among tens and hundreds of millions of consumers (as in the case of the distribution of oil in America and Germany by the American ‘oil trust’) – then it becomes evident that we have socialization of production.…In spite of themselves, the capitalists are dragged, as it were, into a new social order, a transitional social order from complete free competition to complete socialization.…Production becomes social but appropriation remains private.

As a result of the First World War, there occurred the first successful socialist revolution; after the Second World War a third of the world became socialist. I have no wish to be over-schematic or ever to forget the suffering and sacrifices that the creation of modern socialism has involved, but it is undeniable that today the hopes of the overwhelming majority of the world are contained within some form of modern socialism, and that imperialism and capitalism are so much on the defensive that their apologists have to deny their continued existence. For all this the stage was set between 1900 and 1914.

The Cubists knew nothing of the historic necessities and alternatives that were going to reveal themselves. They were not politically concerned. They were not clear even amongst themselves of the meaning of ‘the future’ in which they believed. Perhaps the one item they could have agreed upon was that in the future their Cubist paintings would not look incongruous if hung in the Louvre. They sensed that a qualitative change was taking place and that the bourgeois – whom they hated for his manners and tastes – would soon be outdated: but they did not know why or how. Their sense of change was largely the result of the impact of new inventions and new material possibilities.

Mass production of clothes, shoes, china, paper, food, bicycles had begun in the eighties and nineties. The whole tempo and scale of city life was being altered. The rate of change was acquiring the speed of a machine – and this could be seen in the streets, the shops, the new newspapers.

The Eiffel Tower, which was to remain the highest structure in the world until after 1918 (it is one thousand feet high) and which could only have been built with modern steel, became a symbol of the new possibilities. It had been built for the 1889 International Exhibition, where there were also electrically illuminated fountains which had persuaded people that electricity was the key to a fantastic future. (It was from the nineties but particularly from 1900 onwards that electrical power began to be applied so as to affect people’s lives. This was largely the result of solving the problems of transmitting power over greater distances by the invention of the alternating current and the transformer.) Apollinaire ended a poem he wrote in 1903 as follows:

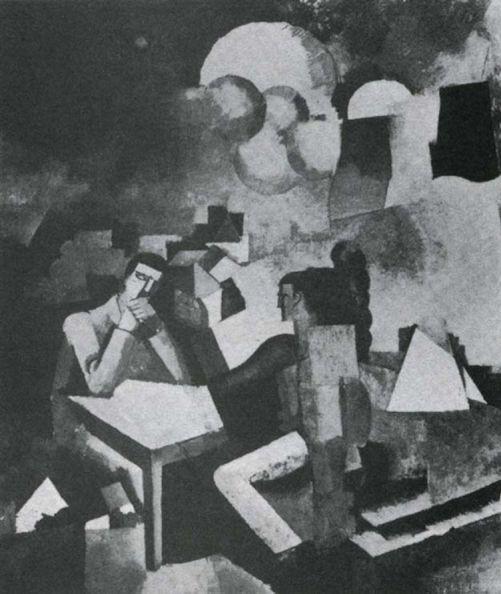

33

Robert Delaunay. The Eiffel Tower. 1910

Paris evenings drunk with gin

Aflare with electricity

Trams with green dorsal lights

Turn machine madness into music

Along the sections of their rails.

Cafés puffed out with smoke

Propose their love of gypsies

And their soda syphons with catarrh

And their waiters dressed in loincloths

To you to you whom I have loved so much.

The Paris Exhibition of 1900 was even more dramatic. There were thirty-nine million visitors. (The organizers had actually expected sixty-five million!) There were contributions from everywhere. There was Esperanto – an international language to further the unity and accessibility of the world. There were motor-cars. There was chromium. There was aluminium. There were synthetic textiles. There was wireless.

At the beginning of the century there were only 3,000 motor vehicles in France. In 1907 there were 30,000. By 1913 France was producing 45,000 a year.

The Wright brothers began working on aeroplanes in 1900. Their first successful flight, lasting fifty-nine seconds, was in 1903. In 1906 Dumont in France made a short flight. In 1908 Wright flew for ninety-one minutes. In 1909 Bleriot crossed the channel:

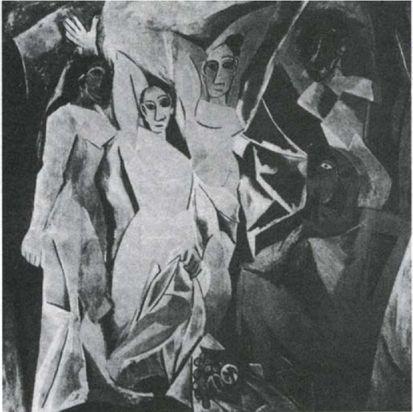

34

Roger de la Fresnaye. Conquest of the Air. 1913

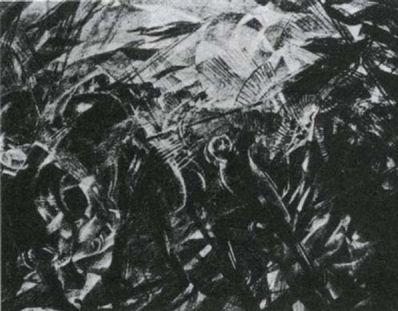

The Cubists’ belief in progress was by no means complacent. They saw the new products, the new inventions, the new forms of energy, as weapons with which to demolish the old order. Yet at the same time their interest was profound and not simply declamatory. In this they differed fundamentally from the

Futurists. The Futurists saw the machine as a savage god with which they identified themselves. Ideologically they were precursors of fascism: artistically they produced a vulgar form of animated naturalism, which was itself only a gloss on what had already been done in films.

35

Carlo Carra. The Funeral of the Anarchist Galli. 1911

The Cubists felt their way, picture by picture, towards a new synthesis which, in terms of painting, was the philosophical equivalent of the revolution that was taking place in scientific thinking: a revolution which was also dependent on the new materials and the new means of production.

The reason why we are on a higher imaginative level [wrote

A. N. Whitehead in 1925

10

] is not because we have finer imaginations, but because we have better instruments. In science the most important thing that has happened during the last forty years is the advance in instrumental design. This advance is partly due to a few men of genius such as Michelson and the German opticians. It is also due to the progress of technological processes of manufacture, particularly in the region of metallurgy.

In 1901 Max Planck published the Quantum Theory. In 1905 Einstein published the Special Theory of Relativity. In 1910 Rutherford discovered the atomic nucleus. By 1905 Newtonian physics – with its mechanistic and some-what

utilitarian emphasis – was superseded. It had come into being with the first promise of the bourgeois state. It had achieved everything that was to be seen in the International Exhibition of 1900. It was superseded as the development of the same bourgeois state reached a point of critical transformation.

The emphasis of modern physics, and indeed all modern science, is on function and process. It denies the fixed state. It substitutes the notion of behaviour for the notion of substance.

Already in the nineteenth century Darwin and Marx had put forward hypotheses which questioned – with facts rather than abstract arguments – the Cartesian division between body and soul. By doing this they also challenged the other fixed categories into which reality had been separated. They saw that such categories had become prisons for the mind, because they prevented people seeing the constant action and interaction between the categories. They found that what distinguished a particular event was always the result of the relationship between that event and other events. If, for a moment, we use the word

space

purely diagrammatically, we can say that they realized that it was in the space

between

phenomena that one would discover their explanation: the space, for example,

between

ape and man: the space

between

the economic structure of a society and the feelings of its members.

This involved a new mode of thinking. Understanding became a question of considering all that was

interjacent

. The challenge of this new mode of thought was foreseen by Hegel. Later it inspired Marx to create the system of dialectical materialism. Gradually it affected all branches of research. Its first tentative formulation in the natural sciences was in the study of electricity. Faraday, wrestling with the problem – as defined in traditional terms – of ‘action at a distance’, invented the concept of a field of force, the electro-magnetic field. Later, in the 1870s, Maxwell defined such a field mathematically.