The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam (5 page)

Read The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam Online

Authors: Jerry Brotton

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance

The religious controversies that followed Luther’s demands in Wittenberg in 1517 had many far-reaching effects, but one of their unintended and often overlooked consequences is in Christianity’s perception of Islam. In 1518 Luther criticized the sale of indulgences to raise money for a new crusade in the Holy Land by arguing provocatively that “to make war on the Turks is to rebel against God, who punishes our sins through them.”

18

Like many medieval theologians, Luther saw the “Turk” as another word for ungodliness, a scourge sent by God to punish a wicked, divided Christianity, part of a mysterious but irresistible divine plan.

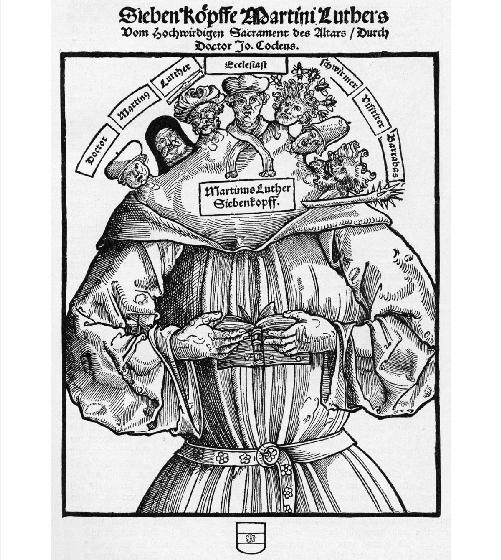

Caricature of Luther with seven heads, including that of a turbaned Turk (1529).

In 1542, the Swiss publisher Johann Herbst was thrown in jail in Basel for printing Robert of Ketton’s translation of the Qur’an in a revised, updated (though still very sketchy) volume produced by Theodore Bibliander, a Protestant reformer, under the title

Machumetis Saracenorum principis vita ac doctrina omnis

(“Life and Teachings of Muhammad, Prince of the Saracens”).

19

Luther intervened, petitioning the Basel authorities to release Herbst and offering to write a preface to the new edition, arguing that it was necessary to understand Islamic theology to refute it. In making this argument in his subsequent preface, Luther described Catholics, Muslims and Jews as all heretical. “Therefore,” he wrote, “as I have written against the idols of the Jews and the papists and will continue to do so to the extent that it is granted to me, so also have I begun to refute the pernicious beliefs of Muhammad.” In his typically blunt manner he went on:

Accordingly I have wanted to get a look at the complete text of the Qur’an. I do not doubt that the more of the pious and learned persons read these writings, the more the errors of the name of Muhammad will be refuted. For just as the folly, or rather the madness, of the Jews is more easily observed once their hidden secrets have been brought to the open, so once the book of Muhammad has been made public and thoroughly examined in all its parts, all pious persons will more easily comprehend the insanity and wiles of the devil and will more easily refute them.

20

Trying to understand Islam through a twelfth-century paraphrase of the Qur’an was never going to get Luther very far. Besides, his Catholic opponents had pounced on his apparent unwillingness to support a crusade against the Turks as proof of the Lutheran “heresy” (Luther had argued that Christianity should fight its own internal demons before turning on the Turks). When Pope Leo X threatened Luther with excommunication in 1520, his position on the Turks was cited as just one of his many “heretical” teachings. In January 1521 Luther was formally excommunicated in the papal bull

Decet Romanum Pontificem

(“It Pleases the Roman Pontiff”) and was himself named a “heretic” and “schismatic.”

21

Luther later changed his mind about waging war on the Turks, arguing that this was the prerogative of rulers, not of clergy. He continued to describe Catholicism, Islam and Judaism as conjoined enemies of the “true” Christian faith, reserving his bitterest polemic for Pope Clement VII and the Ottomans: “as the pope is Antichrist,” he wrote in 1529, “so the Turk is the very devil.”

22

Catholics responded by depicting Luther as a divided monster with seven heads, one sporting a Turkish turban. Francesco Chieregato, one of the pope’s advisers at the Diet of Nuremberg (convened to discuss church reform), wrote in January 1523 that he was “occupied with the negotiations for the general war against the Turk, and for that particular war against that nefarious Martin Luther, who is a greater evil to Christendom than the Turk.”

23

When Thomas More, author of

Utopia

and privy councillor to Henry VIII, was asked to respond to the Lutheran challenge, his

Dialog Concerning Heresies

(1528) referred to “Luther’s sect” as worse than “all the Turks, all the Saracens, all the heretics.”

24

More’s close friend the great humanist scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam tried to find a middle way between Catholic and Protestant sectarian divisions in his

De bello turcico

(“On the War Against the Turks”). Erasmus’s treatise was written in 1530 to coincide with the Diet of Augsburg, a general assembly called by Charles V to discuss what he regarded as the two greatest threats facing Christendom: Lutheranism and Islam. Charles’s advisers encouraged him to use the assembly to pursue the policies adopted by his grandparents Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile toward Muslims in Spain: forced conversion or expulsion. “Luther’s diabolical and heretical opinions,” wrote Cardinal Lorenzo Campeggio, “shall be castigated and punished according to the rule and practice observed in Spain with regard to the Moors.”

25

But Luther was only one-half of Charles’s problem: the other was the spectacular rise of the Ottoman Empire, which by 1530 was knocking on the door of Christendom. Having taken Constantinople in 1453, the Ottomans had conquered Egypt and Syria and were challenging the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean. During the 1520s a series of military campaigns across the Balkans led to the capture of Belgrade and the invasion of Hungary, creating an Islamic empire that spanned three continents and ruled an estimated 15 million people. Just months before Erasmus wrote his treatise, Ottoman imperial expansion into Europe reached its zenith, with an Ottoman army at the gates of Vienna. Süleyman the Magnificent taunted the besieged Christian forces by parading outside the gates wearing an extravagant, bejeweled helmet made for him by Venetian goldsmiths that consciously emulated the Habsburg and papal imperial crowns.

26

It had proved almost impossible to unite Christendom against the Ottomans: Venice remained on amicable commercial terms with them, while the French pursued repeated diplomatic and military alliances with Süleyman as a bulwark against the Habsburgs. Worse still, there were rumors that Süleyman, having learned of the threat posed by Luther to his great enemy Charles V, was encouraging his imams in the mosques of Constantinople to pray for Luther’s success.

27

With many of the German states in the grip of Lutheranism on one side and the Ottomans in control of much of eastern Europe on the other, this was a critical moment for Catholicism, and Erasmus knew it. How, he asked, had the Ottomans “reduced our religion from a broad empire to a narrow strip?” The answer reverted to medieval commonplaces about Islamic paganism and heresy. Referring to what he called “this race of barbarians, their very origin obscure,” Erasmus argued that the Ottoman “sect” was “a mixture of Judaism, Christianity, paganism, and the Arian [non-Trinitarian] heresy. They acknowledge Christ—as just one of the prophets.” As was true of his medieval theological predecessors, Erasmus’s interest in Islam was secondary to the assumption that the faith was just a projection of a divided Christianity. “They rule because God is angered,” Erasmus continued; “they fight us without God, they have Mahomet as their champion, and we have Christ—and yet it is obvious how far they have spread their tyranny, while we, stripped of so much power, ejected from much of Europe, are in danger of losing everything.”

28

Erasmus’s solution to the Turkish problem took on far greater significance when set against sixteenth-century Christian divisions. “If we really want to heave the Turks from our neck,” he concluded, “we must first expel from our hearts a more loathsome race of Turks, avarice, ambition, the craving for power, self-satisfaction, impiety, extravagance, the love of pleasure, deceitfulness, anger, hatred, envy.” Writing as a Catholic, but sounding very much like a Lutheran, Erasmus implored his readers to “rediscover a truly Christian spirit and then, if required, march against the flesh-and-blood Turk.”

29

Christianity needed reformation, but it also needed unification; otherwise, the Turk buried within the heart of all believers, be they Catholic or Lutheran, would triumph. Trying to please both sides of a divided Christendom, Erasmus enabled Catholics to castigate Protestants as akin to Turks for dividing the faith, while also enabling Protestants to condemn Catholics as the worst representatives of “Turkish” avarice and impiety.

Those assembled at Augsburg responded as they usually did to humanist advice and ignored Erasmus’s treatise, which was, for all its theological eloquence, vague in its practical application. The Diet did little other than keep the Habsburgs on a collision course with both Luther and the Turk, although the pressure to confront the Ottoman threat enabled Lutheranism to survive and prosper in these crucial early years of its emergence. Throughout the 1540s Charles V fought the dual “heresy” on two fronts and with mixed success. In 1541 he tried to follow his conquest of Tunis with an attack on Algiers, but the campaign was a complete disaster. By 1545 he was at war with Lutheran forces in Germany, which this time culminated in victory at the Battle of Mühlberg in 1547.

• • •

The arrival of the

Conquest of Tunis

tapestries in London in 1554 not only reminded those who saw them of Charles’s earlier victory over Islam but invited inevitable comparisons with the defeat of Lutheranism at Mühlberg. Within weeks of seeing the Tunis tapestries, Mary and Philip set about stamping out the Lutheran “heresy” that had taken hold of England during Edward VI’s reign. Legislation was prepared to restore papal authority in ecclesiastical matters, and in November an act was passed for the “avoiding of heresies which have of late arisen, grown and much increased within this realm.”

30

By February 1555 the first public burnings began of “heretical” Lutherans, which would secure the queen’s enduring historical notoriety as “Bloody Mary.”

History is rarely kind to the losers, and Mary is no exception. Her short-lived restoration of Catholicism would forever pale in comparison with her half sister Elizabeth’s forty-five-year Protestant reign, which became a touchstone of English national identity. For centuries Mary was condemned as a religious zealot who had pursued a murderous crusade against Protestants and prepared to sacrifice her crown to the Spanish Catholics rather than see the Reformation triumph in England. Much of this was due to the Protestant theologian John Foxe’s

Acts and Monuments

(1563), popularly known as

Foxe’s Book of Martyrs,

a polemical account of the Catholic persecution of Protestants, under what he called “the horrible and bloody time of Queen Mary.”

31

More recent evaluations reveal a more complex picture of her reign.

32

Although she passed legislation relinquishing her title as head of the church and giving the pope jurisdiction over English ecclesiastical matters, Mary maintained a clear distinction between her religious and secular power. She quietly retained her father’s statutes defining England as an empire over which she, and not the papacy or Philip, exerted

plenum dominium

(complete ownership) and ensured in all official documentation and on public occasions that she took royal precedence over Philip in their controversial co-monarchy. In a country that remained in most areas predominantly Catholic despite the reformed experiments of Edward VI’s reign, Mary’s marriage to Philip was welcomed by at least as many as opposed it. Eager to guarantee the City’s position at the center of a commercial network that looked to Spain and the Low Countries for much of its export market, London’s merchants were so supportive of the marriage that they designed and paid for the couple’s carefully choreographed entry into London in August 1554.

33

Such elaborate spectacles were also used by the newly married couple in the courtly festivities that took place during their London residence in the winter of 1554–1555. On Shrovetide, February 26, 1555, pageants were staged with actors dressed as Turkish magistrates, Turkish archers and Turkish women. Exactly what they performed was not recorded, but they presumably represented vices of some kind, intended as foils to Christian virtues. The costumes survived and were used throughout the 1560s in performances under Elizabeth I.

34

• • •

Upon her accession, Mary swiftly acted to encourage international trade by stressing a surprising degree of continuity with her father’s and half brother’s foreign and commercial policies. Henry VIII’s merchants had advised him as early as the 1520s that the dominance over global trade of the Spanish, Portuguese and Ottoman empires gave them little room in which to pursue their own commercial interests. To the west, Spain dominated the newly discovered Americas and exploited their silver and gold. To the south Portugal monopolized Africa and the eastern trade routes, objecting when English merchants sought to establish trade with Morocco and Guinea. And to the east the overland route to Asia lay in the hands of the Ottomans. In 1527 Robert Thorne, an English merchant based in Seville, advised Henry that the only way to outmaneuver his imperial rivals and reach the Spice Islands in Indonesia was to order his merchants to sail north. By “sailing northwards and passing the Pole, descending to the Equinoctal line,” Thorne explained, “we shall hit these islands, and it should be a much shorter way, than either the Spanish or the Portuguese have.” He speculated that the northern polar region contained a navigable temperate belt beyond the freezing Norwegian seas. His hope was that English merchants could develop an export trade “profitable to our commodities of cloth” while importing spices.

35