The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (52 page)

Read The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy Online

Authors: Irvin D. Yalom,Molyn Leszcz

Tags: #Psychology, #General, #Psychotherapy, #Group

Bowlby’s work on attachment

22

has also spawned new work that categorizes individuals on the basis of four fundamental styles of relationship attachment: 1) secure; 2) anxious; 3) detached or dismissive and avoidant; and 4) fearful and avoidant.

23

Some therapists feel that these attachment styles are so important that the therapist’s recognition and appropriate therapeutic responsiveness to them may make or break treatment.

24

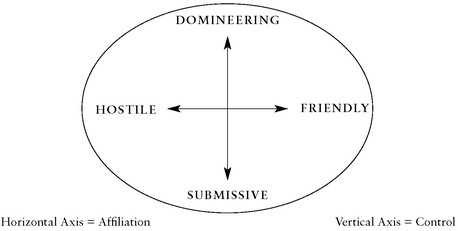

Contemporary interpersonal theorists† have attempted to develop a classification of diverse interpersonal styles and behavior based on data gathered through interpersonal inventories (often the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems, IIP).

25

They then place this information onto a multidimensional, interpersonal circumplex (a schematic depiction of interpersonal relations arranged around a circle in two-dimensional space; see

figure 9.1

).

26

Two studies that used the interpersonal circumplex in a twelve-session training group of graduate psychology students generated the following results:

1. Group members who were avoidant and dismissive were much more likely to experience other group members as hostile.

2. Group members who were anxious about or preoccupied with relationships saw other members as friendly.

3. Strongly dominant individuals resist group engagement and may devalue or discount the group.

27

FIGURE 9.1

Interpersonal Circumplex

An illustrative example of this type of research may be found in a well-constructed study that tested the comparative effectiveness of two kinds of group therapy and attempted to determine the role of clients’ personality traits on the results.

28

The researchers randomly assigned clients seeking treatment for loss and complicated grief (N = 107) to either a twelve-session interpretive/expressive or a supportive group therapy. Client outcome assessments included measures of depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and social adjustment. Before therapy, each client was given the NEO-Five Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI), which measures five personality variables: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness.

29

What did the study find?

1. Both group therapies were demonstrably effective, although the interpretive group generated much greater affect and anxiety among the group members.

2. One personality factor, neuroticism, predicted poorer outcome in both types of group.

3. Three factors predicted good outcomes with both treatments: extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness.

4. The fifth factor, agreeableness predicted success in the interpretive/ expressive group therapy but not in the supportive group therapy.

The authors suggest that the agreeableness factor is particularly important in sustaining relatedness in the face of the challenging work associated with this form of intensive group therapy.

Two other personality measures relevant to group therapy outcome have also been studied in depth: psychological-mindedness

30

and the Quality of Object Relations (QOR) Scale.

31

w

Both of these measures have the drawback of requiring that the client participate in a 30–60-minute semistructured interview (in contrast to the relative ease of a client self-report instrument such as the NEO-FFI).

Psychological-mindedness predicts good outcome in all forms of group therapy. Psychologically minded clients are better able to work in therapy—to explore, reflect, and understand. Furthermore, such clients are more accountable to themselves and responsible to comembers.

32

Clients with higher QOR scores, which reflect greater maturity in their relationships, are more likely to achieve positive outcomes in interpretive/expressive, emotionactivating group therapy. They are more trusting and able to express a broader range of negative and positive emotions in the group. Clients with low QOR scores are less able to tolerate this more demanding form of therapy and do better in supportive, emotion-suppressing group formats.

33

Once we identify a key problematic interpersonal area in a client, an interesting question arises: do we employ a therapy that

avoids

or

addresses

that area of vulnerability? The large NIMH study of time-limited therapy in the treatment of depression demonstrated that clients do not necessarily do well when matched to the form of therapy that appears to target their specific problems. For example, clients with greater interpersonal difficulty did less well in the interpersonal therapy. Why would that be?

The answer is that

some

interpersonal competence is required to make use of interpersonal therapy. Clients with greater interpersonal dysfunction tend to do better in cognitive therapy, which requires less interpersonal skill. Conversely, clients with greater cognitive distortions tend to achieve better results with interpersonal therapy than with cognitive therapy. An additional finding of the NIMH study is that perfectionistic clients tend to do poorly in time-limited therapies, often becoming preoccupied with the looming end of therapy and their disappointment in what they have accomplished.

34

Summary: Group compositional research is still a soft science. Nonetheless, some practical treatment considerations flow from the research findings. Several key principles can guide us in composing intensive interactional psychotherapy groups:

•

Clients will re-create their typical relational patterns within the microcosm of the group.

•

Personality and attachment variables are more important predictors of in-group behavior than diagnosis alone.

•

Clients require a certain amount of interpersonal competence to make the best use of interactional group therapy.

•

Clients who are rigidly domineering or dismissive will impair the work of the therapy group.

•

Members eager for engagement and willing to take social risks will advance the group’s work.

•

Psychologically minded clients are essential for an effective, interactional therapy group; with too few such clients, a group will be slow and ineffective.

•

Clients who are less trusting, less altruistic, or less cooperative will likely struggle with interpersonal exploration and feedback and may require more supportive groups.

•

Clients with high neuroticism or perfectionism will likely require a longer course of therapy to effect meaningful change in symptoms and functioning.

Direct Sampling of Group-Relevant Behavior.

The most powerful method of predicting group behavior is to observe the behavior of an individual who is engaged in a task closely related to the group therapy situation.

35

In other words

, the closer we can approximate the therapy group in observing individuals, the more accurately we can predict their in-group behavior

. Substantial research evidence supports this thesis. An individual’s behavior will show a certain consistency over time, even though the people with whom the person interacts change—as has been demonstrated with therapist-client interaction and small group interaction.

36

For example, it has been demonstrated that a client seen by several individual therapists in rotation will be consistent in behavior (and, surprisingly, will change the behavior of each of the therapists!).

37

Since we often cannot accurately predict group behavior from an individual interview,

we should consider obtaining data on behavior in a group setting.

Indeed, business and government have long found practical applications for this principle. For example, in screening applicants for positions that require group-related skills, organizations observe applicants’ behavior in related group situations. A group interview test has been used to select Air Force officers, public health officers, and many types of public and business executives and industry managers. Universities have also made effective use of group assessment to hire academic faculty.

38

This general principle can be refined further: group dynamic research also demonstrates that behavior in one group is consistent with behavior in previous groups, especially if the groups are similar in composition,

39

in group task,

40

in group norms,

41

in expected role behavior,

42

or in global group characteristics (such as climate or cohesiveness).

43

In other words, even though one’s behavior is broadly consistent from one group to the next, the individual’s specific behavior in a new group is influenced by the task and the structural properties of the group and by the specific interpersonal styles of the other group members.

The further implication, then, is that we can obtain the most relevant data for prediction of group behavior by observing an individual behave in a group that is

as similar as possible to the one for which he or she is being considered.

How can we best apply this principle? The most literal application would be to arrange for the applicant to meet with the therapy group under consideration and to observe his or her behavior in this setting. In fact, some clinicians have attempted just that: they invite prospective members to visit the group on a trial basis and then ask the group members to participate in the selection process.

44

Although there are several advantages to this procedure (to be discussed in chapter 11), I find it clinically unwieldy: it tends to disrupt the group; the members are disinclined to reject a prospective member unless there is some glaring incompatibility; furthermore, prospective members may not act naturally when they are on trial.

An interesting research technique with strong clinical implications is the waiting-list group—a temporary group constituted from a clinic waiting list. Clinicians observe the behavior of a prospective group therapy member in this group and, on the basis of the data they obtain there, refer the individual to a specific therapy or research group. In an exploratory study, researchers formed four groups of fifteen members each from a group therapy waiting list; the groups met once a week for four to eight weeks.

45

Waiting-list group behavior of the clients not only predicted their behavior in their subsequent long-term therapy group but also enhanced the clients’ engagement in their subsequent therapy group. They concluded, as have other researchers using a group diagnostic procedure for clients applying for treatment, that clients did not react adversely to the waiting-list group.

46

It is challenging to lead waiting list groups. It requires an experienced leader who has the skill to sustain a viable group in an understaffed setting dealing with vulnerable and often demoralized clients.

47

In one well-designed project, thirty clients on a group therapy waiting list were placed into four one-hour training sessions. The sessions were all conducted according to a single protocol, which included an introduction to here-and-now interaction.

48

The researchers found that each client’s verbal participation and interpersonal responsivity in the training sessions correlated with their subsequent behavior during their first sixteen group therapy sessions. These findings were subsequently replicated in another, larger project.

49

Summary: A number of studies attest to the predictive power of observed pretherapy group behavior. Furthermore, there is a great deal of corroborating evidence from human relations and social-psychological group research that subsequent group behavior may be satisfactorily predicted from pretherapy waiting or training groups.†

The Interpersonal Intake Interview.

For practitioners or clinics facing time or resource pressures, the use of trial groups may be an intriguing but highly impractical idea. A less accurate but more pragmatic method of obtaining similar data is an interpersonally oriented interview in which the therapist tests the prospective group client’s ability to deal with the interpersonal here-and-now reality. Is the client able to comment on the process of the intake interview or to understand or accept the therapist’s process commentary? For example, is the client obviously tense but denies it when the therapist asks? Is the client able and willing to identify the most uncomfortable or pleasant parts of the interview? Or comment on how he or she wishes to be thought of by the therapist?