The Victorian Internet (12 page)

Read The Victorian Internet Online

Authors: Tom Standage

On the other hand, the telegraph was sometimes able to help couples transcend real-world barriers. In 1876 William Storey,

the operator at an army base at Camp Grant, Arizona, thought he was going to have to call off his wedding; he was unable to

obtain a leave of absence to travel to San Diego to get married, and there was no minister at the camp to perform the wedding,

so there was little point in his fiancee making the trip to Camp Grant. But then Storey had an idea. "A contract by telegraph

is binding, then why," he thought, "can we not be married by telegraph?" He hit upon the plan of inviting his fiancee, Clara

Choate, to Camp Grant and asking a minister to per form the marriage ceremony remotely, by telegraph. Choate made the wagon

trip to the camp, and the Reverend Jonathan Mann agreed to marry them from 650 miles away in San Diego.

Lieutenant Philip Reade, who was in charge of the telegraph lines in California and Arizona, arranged for the line to be cleared

after working hours so that the wedding could take place. He sent out a message to all station managers along the line, informing

them that the line would be used "for the purpose of conducting a marriage ceremony by telegraph between San Diego and Camp

Grant, and you and your friends are specially invited to be present on the occasion, to assist if necessary and to see that

good order is maintained." The operators duly accepted the invitation, and at 8:3o P.M. on April 24 a message arrived from

the father of the bride in San Diego that he and the minister were ready to proceed. The minister then read out the marriage

service, which was relayed to Camp Grant as he spoke. At the appropriate point in the service the bride and groom tapped on

the telegraph key to indicate a solemn "I do." Once the service was over, messages of congratulations flooded in from all

the stations on the line. The groom was for many years afterward greeted by fellow telegraph operators, who, upon hearing

his name, exclaimed that they had been present at his wedding.

The telegraph could also bring together operators working in the same office. "Making Love by Telegraph," another article

published in

Western Electrician

in 1891, tells the story of a particularly difficult wire in the New York telegraph station that was connected to a number

of district railway offices manned by inexperienced and often incompetent operators. As a result, most operators rapidly lost

their temper whenever they tried to work the wire: "It did not matter how good an operator was or how hard he tried to get

along, his patience could not stand the strain for more than a few minutes." But there was one female operator who never had

any trouble, so she ended up working the wire. One summer a new operator arrived and was assigned to cover the wire during

her lunch hour. He was a good-tempered man, but within ten minutes of taking his station he was involved in "a red hot row"

with one of the rural operators. It lasted until the young woman got back, when she graciously straightened matters out. The

same thing happened day after day, and after a while the young man started to fall in love with the woman. He realized that

"nothing short of an angel could work that wire, and he cultivated her acquaintance. They have been married a long time now,"

the article concludes, "and he has told the secret to his friends matrimonially inclined, and a number of them have been watching

that wire ever since. No young woman has remained there for any length of time, and the watchers all know what it means."

T

HERE WAS ALSO a dark side to telegraphic interaction; the best operators often felt nothing but scorn toward the small-town,

part-time operators they often encountered on-line, who were known as "plugs" or "hams." Speed was valued above all else?

the fastest operators were known as bonus men, because a bonus was offered to operators who could exceed the normal quota

for sending and receiving messages. So-called first-class operators could handle about sixty messages an hour—a rate of twenty-five

to thirty words per minute—but the bonus men could handle even more without a loss in accuracy, sometimes reaching speeds

of forty words per minute or more.

Wandering workers who went from job to job were known as "boomers." There were no formal job interviews; applicants were simply

sat down on a busy wire to see if they could handle it. Since they could find work almost anywhere, many boomers had an itinerant

lifestyle; a great number of them suffered from alcoholism or mental health disorders. In a sense, the telegraph community

was a meritocracy—it didn't matter who you were as long as you could send and receive messages quickly—which was one of the

reasons that women and children were readily admitted to the profession.

New operators usually started out by filling in on an occasional basis or taking seasonal jobs at parks, summer camps, and

resorts, and the more talented would soon gravitate toward the cities. Once a young operator had gained a foothold in a city

office, he or she could expect to be subjected to a humiliating induction ritual, known as "salting." Sometimes the operator

would be sent bogus messages addressed to "L. E. Phant" or "Lynn C. Doyle." But usually the unwary beginner would be asked

to operate a wire with a particularly fast sender at the other end, who would start sending at a reasonable rate but then

gradually pick up the pace. As the novice operator struggled to keep up, the other operators in the office would soon gather

round to watch, and eventually the operator would be forced to admit defeat and "break." Salting was also known as hazing

or rushing.

Young Thomas Edison was legendary for being able to take down messages as fast as anyone could transmit them. Edison was taught

Morse code as a teenager by a railway stationmaster, whose three-year-old son he had plucked from the path of an oncoming

train. He rapidly became an expert operator, and there are numerous tales of his prowess. At one stage the disheveled Edison

took a job in Boston, where the operators thought rather highly of themselves and liked to dress like gentlemen. Taking him

for a country bumpkin, they asked a very fast operator in another office to salt him. But as the speed of transmission increased,

Edison kept on receiving happily at twenty-five, thirty, even thirty-five words per minute. Finally, having received all the

messages without any difficulty, Edison tapped back to his opponent: "Why don't you use your other foot? "

Edison's ability arose from his partial deafness, which meant that he was not distracted by background noise as he sat listening

to the clicks of the telegraph receiver. In later life, he even turned his deafness to his advantage when courting his second

wife, Mina. "Even in my courtship my deafness was a help," he wrote in his diary. "In the first place it excused me for getting

quite a little nearer to her than I would have dared to if I hadn't had to be quite close in order to hear what she said.

My later courtship was carried on by telegraph. I taught the lady of my heart the Morse code, and when she could both send

and receive we got along much better than we could have with spoken words by tapping out our remarks to one another on our

hands. Presently I asked her thus, in Morse code, if she would marry me. The word 'Yes' is an easy one to send by telegraphic

signals, and she sent it. If she had been obliged to speak it, she might have found it harder."

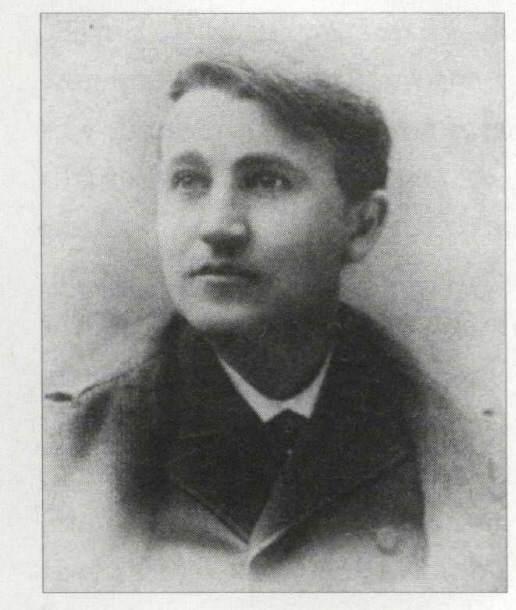

Thomas Edison, inventor, telegraph pioneer and operator.

Edison was, like many telegraphers, an inveterate tin-kerer who liked to try out new and improved forms of telegraphic apparatus.

He preferred to take the night shift so he could spend the day experimenting in a back room at the telegraph office, and he

lived on a frugal diet of apple pie washed down with vast amounts of coffee. But when his experiments went wrong, which they

often did, he would lose his job and would have to move on to another town. On one occasion he blew up a telegraph office

when mixing new battery acid to a recipe of his own devising; another time he spilled sulfuric acid on the floor of a telegraph

office above a bank, and the acid ate through the floor and ruined the carpet and furniture in the office below.

But Edison's prowess as an operator enabled him to progress through the ranks of the telegraphic community, and eventually

he went right to the top, working as an engineer and inventor and reporting directly to the directors of the major telegraph

companies. Indeed, despite the strange customs and the often curious lifestyle of many operators, telegraphy was regarded

as an attractive profession, offering the hope of rapid social advancement and fueling the expansion of the middle class.

Courses, books, and pamphlets teaching Morse code to beginners flourished. For the ambitious, it provided an escape route

from small towns to the big cities, and for those who liked to move around, it meant guaranteed work wherever they went.

Admittedly, there was a rapid turnover of employees in major offices, and telegraphers often had to endure unsociable hours,

long shifts, and stressful and unpleasant working conditions. But to become a telegrapher was to join a vast on-line community—and

to seek a place among the thousands of men and women united via the worldwide web of wires that trussed up the entire planet.

WAR AND PEACE IN THE GLOBAL VILLAGE

All the inhabitants of the earth would be brought into one intellectual neighborhood.

—Alonzo Jackman, advocating an Atlantic telegraph in 1846

D

ESPITE THE WIDELY expressed optimism that the telegraphs would unite humanity, it was in fact only the telegraph operators

who were able to communicate with each other directly. But thanks to the telegraph, the general public became participants

in a continually unfolding global drama, courtesy of their newspapers, which were suddenly able to report on events on the

other side of the world within hours of their occurrence. The result was a dramatic change in world-view; but to appreciate

the extent to which the telegraph caused an earthquake in the newspaper business requires an understanding of how newspapers

were run in the pre-telegraph era.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, newspapers tended to cover a small locality, and news traveled as the papers themselves

were carried from one place to another. One journalist, Charles Congdon, complained that in those days there was hardly anything

in his local New England newspaper. "In that time of small things," he wrote in his memoirs, "subscribers must have been easily

satisfied. The news from Europe, when there was any, was usually about six weeks old, or even older." There were very few

letters from foreign correspondents, he noted, which was a good thing, "for most of them were far from interesting."

Today, the common perception of a journalist is someone who will stop at nothing to get hold of a story and rush it into the

newsroom. But in the early nineteenth century, newspapers traded on their local coverage, not the timeliness of their news.

Congdon tells of one editor who refused a journalist's request to visit a nearby town to report on a speech, saying "Somebody

will send us in something about it in two or three days." Some newspapers printed on a different day each week to fit in with

the social life of the editor; others rationed the amount of news they printed in a busy week, in case there was a shortage

of news the following week. And apart from local stories, most other news was taken from the pages of other papers, which

were delivered by post—days after publication. Newspapers reprinted each other's stories freely; news moved so slowly that

there was no danger that one paper would steal another's story and be on sale at the same time. The free exchange of information

that resulted was beneficial to all concerned, though it meant that news was often days or weeks old by the time it reached

its readers.

In addition, some of the larger newspapers had correspondents in foreign countries, who would write in to report the latest

news from distant cities. Their letters took weeks to arrive, but before the establishment of the telegraph network, there

was no other way to send news. It was commonplace for foreign news to be weeks or months old by the time it appeared in print.

The

Times

of London had a particularly extensive network of foreign correspondents, so that its largely business readership could be

kept informed of overseas political developments that might affect trade. Foreign reports also reported the arrival and departure

of ships and detailed their cargoes. Rut since the news traveled no faster than the ships that carried it, the January 9,

1845, edition of the Times included reports from Cape Town that were eight weeks old and news from Rio that was six weeks

old. The delay for news from New York was four weeks, and for news from Rerlin a week. And the

Times

was a newspaper that prided itself on getting the news by the fastest means possible.

The existence of a newspaper tax in Britain kept prices artificially high, so the

Times

had the market to itself. But in New York things started to heat up in the 1820s with the fierce competition between the

Journal of Commerce

and the rival

Courier and Enquirer.

Both papers were aimed at business readers and fought to distinguish themselves by being first with the news. They established

rival pony expresses between New York and Washington to get the political news sooner, and used fast boats to meet incoming

vessels from Europe and get the latest news before they docked. Then, in the 1830s, newspapers became a popular medium with

the establishment of cheap, mass-market titles. The ensuing rivalry between the newspapers of the so-called penny press led

to an increase in the use of carrier pigeons and ships. One editor, James Gordon Bennett of the

New York Herald,

even agreed to pay one of his sources a $500 bonus for every hour European news arrived at the

Herald

in advance of its competitors. Get the news first, and you'll sell more papers: Increasingly, news was worth money.

So it was clear that the establishment of telegraph lines in the 1840s would change everything. In fact, the second message

sent on Morse's Washington-Baltimore line—immediately after "WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT"—was "HAVE YOU ANY NEWS?" But far from

welcoming the telegraph, many newspapers feared it.

a

LTHOUGH RECEIVING news by telegraph would seem to be the logical next step from using horses, carrier pigeons, and so on,

it was instead viewed as an ominous development. The telegraph could deliver news almost instantly, so the competition to

see who could get the news first was, in effect, over. The winner would no longer be one of the newspapers; it would be the

telegraph. James Gordon Bennett was one of many who assumed that the telegraph would actually put newspapers out of business;

because it put all newspapers on a level playing field, his shenanigans to get hold of the news earlier than his rivals would

no longer be an advantage. "The telegraph may not affect magazine literature," he suggested, "but the mere newspapers must

submit to destiny, and go out of existence." The only role left for printed publications, it seemed, would be to comment on

the news and provide analysis.

Of course, this perception turned out to be wrong. While the telegraph was a very efficient means of delivering news to newspaper

offices, it was not suitable for distributing the news to large numbers of readers. And although the telegraph did indeed

dramatically alter the balance of power between providers and publishers of information, the newspaper proprietors soon realized

that, far from putting them out of business, it actually offered great opportunities. For example, breaking news could be

reported as it happened, in installments—increasing the suspense and boosting sales. If there were four developments to a

major story during the day, newspapers could put out four editions—and some people would buy all four.

But with news available instantly from distant places, the question arose, Who ought to be doing the reporting? Reporters

as we know them today did not exist. So who should get the news? One suggestion was that telegraph operators, who were sprinkled

all over the world, should act as reporters. But the handful of telegraph companies that tried to press operators into journalistic

service, and then sell their reports to newspapers, found that operators tended to make pretty hopeless journalists. On the

other hand, if each newspaper sent its own writer to cover a far-off story, they all ended up sending similar dispatches back

from the same place along the same telegraph wire, at great expense.

The logical solution was for newspapers to form groups and cooperate, establishing networks of reporters whose dispatches

would be telegraphed back to a central office and then made available to all member newspapers. This would give newspapers

the advantage of a far greater reach than they would have had otherwise, without the expense of maintaining dozens of their

own reporters in far-flung places. In the United States, the first and one of the best known of these organizations, which

came to be called news agencies, was the New York Associated Press, a syndicate of New York newspapers set up in 1848 that

quickly established cozy relationships with the telegraph companies and was soon able to dominate the business of selling

news to newspapers.

In Europe, meanwhile, Paul Julius von Reuter was also establishing a news agency. Rorn in Germany, Reuter started out working

for a translation house that took stories from various European newspapers, translated them into different languages, and

redistributed them. Reuter soon realized that some stories were more valuable than others, and that businessmen in particular

were willing to pay for timely information, so he set up his own operation, using carrier pigeons to supply business information

several hours before it could be delivered by mail. Initially operating between Aix-la-Chapelle and Brussels, the Reuter

network of correspondents extended across Europe during the 1840s. Each day, after the afternoon close of the stock markets,

Reuter's representative in each town would take the latest prices of bonds, stocks, and shares, copy them onto tissue paper,

and place them in a silken bag, which was taken by homing pigeon to Reuter's headquarters. For security, three pigeons were

sent, carrying copies of each message. Reuter then compiled summaries and delivered them to his subscribers, and he was soon

supplying rudimentary news reports too.

When the electric telegraph was established between Aix-la-Chapelle and Berlin, Reuter started to use it alongside his pigeons;

when England and France were linked by telegraph in 1851, Reuter moved to London. His policy was "follow the cable," so London

was the place to be, since it was both the financial capital of the world and the center of the rapidly expanding international

telegraph network.

Although Reuter's reports of foreign events were initially very business oriented—the only angle his business customers were

interested in was how trade would be affected—he soon started trying to sell his dispatches to newspapers. With the abolition

of the newspaper tax in Britain in 1855, several new newspapers sprung up, but only the

Times

was capable of covering foreign news, thanks to its well-established network of correspondents who, after some reluctance,

started using the telegraphs. The

Times

preferred to use its own reports rather than buy them from Reuter, and turned down the opportunity to do a deal with him three

times. Eventually Reuter proved the value of his service in 1859 when he obtained a copy of a crucial French speech concerning

relations with Austria and was able to provide it to the

Times

in London within two hours of its being delivered in Paris. During the ensuing war, with the French and Sardinians on one

side, and the Austrians on the other, Reuter's correspondents reported from all three camps—and on one occasion dispatched

three separate reports of the same battle from the point of view of each of the armies involved. Even so, the

Times

still preferred to rely on its own correspondents, but Reuter was able to sell his dispatches to its rival London newspapers,

thus helping them compete with the

Times

without having their own foreign correspondents.

And readers just couldn't get enough foreign news—the more foreign, the better. Instead of limiting their coverage to a small

locality, newspapers were able for the first time to give at least the illusion of global coverage, providing a summary of

all the significant events of the day, from all over the world, in a single edition. We take this for granted today, but at

the time the idea of being able to keep up with world affairs, and feel part of an extended global community, was extraordinary.

It was great for sales, too. "To the press the electric telegraph is an invention of immense value," declared one journalist.

"It gives you the news before the circumstances have had time to alter. The press is enabled to lay it fresh before the reader

like a steak hot from the gridiron, instead of being cooled and rendered flavourless by a slow journey from a distant kitchen.

A battle is fought three thousand miles away, and we have the particulars while they are taking the wounded to the hospital."

The thirst for foreign news was such that when the first transatlantic telegraph cable was completed in 1858, one of the few

messages to be successfully transmitted was the news from Europe, as provided by Reuter. "PRAY GIVE US SOME NEWS FOR NEW YORK,

THEY ARE MAD FOR NEWS," came the request down the cable from Newfoundland. And so on August 27, 1858, the news headlines were

as follows: "EMPEROR OF FRANCE RETURNED TO PARIS. KING OF PRUSSIA TOO ILL TO VISIT QUEEN VICTORIA. SETTLEMENT OF CHINESE QUESTION.

GWALIOR INSURGENT ARMY BROKEN UP. ALL INDIA BECOMING TRANQUIL."

This last headline indicated that the Indian Mutiny, a serious rebellion against Rritish rule that had broken out the year

before, had been suppressed. However, General Trollope, commander of the Rritish forces in Halifax, Nova Scotia, had received

an order a few weeks earlier by sea from his superiors in London, asking him to send two regiments of troops back across the

Atlantic so that they could be redeployed in India. It is not clear whether or not Trollope was aware of the Reuter report,

but it clearly indicated that his troops were no longer needed. A telegram from London to General Trollope countermanding

the original order was hurriedly sent down the new Atlantic cable, telling him to stay put, and saving the British government

£50,000 at a stroke—more than paying back its investment in the cable. It was one of the last messages to reach North America

via the ill-fated cable, which stopped working the next day.

But what if the cable had failed earlier? Had he been aware of the Reuter report, Trollope would have known that there was

in fact no need for him to send his troops to India, though he would have no doubt followed orders and sent them anyway. This

was just one example of how the rapid and widespread distribution of foreign news had unforeseen military and diplomatic implications-something

that was brought home to everyone during the Crimean War.

D

URING WARTIME, the existence of an international telegraph network meant that news that had hitherto been safe to reveal

to newspapers suddenly became highly sensitive, since it could be immediately telegraphed directly into the hands of the enemy.

For years it had been customary in Rritain for news of departing ships to be reported as they headed off to foreign conflicts;

after all, the news could travel no faster than the ships themselves. Rut the telegraph meant that whatever information was

made available in one country was soon known overseas. This took a lot of getting used to, both by governments and news organizations.