The Victorian Internet (16 page)

Read The Victorian Internet Online

Authors: Tom Standage

As enthusiasm for all things electrical blossomed in the 1880s and the telephone continued its rapid growth, the telegraph

was no longer at the cutting edge of technology. "So much have times altered in the last fifty years that the electric telegraph

itself is threatened in its turn with serious rivalry at the hands of a youthful and vigourous competitor. A great future

is doubtless in store for the telephone," declared

Chambers Journal

in 1885.

By this time, many telegraphers were complaining that they had been reduced to mere machines, while others decried the declining

quality of those entering the profession. "The character of the business has wholly changed," lamented the

Journal of the Telegraph.

"It cannot now subserve public interests or its own healthful development without the precision and uniformity of mechanism."

But the changing fortunes of telegraphy were perhaps most vividly illustrated in the way the telegraphic journals, which had

covered the rise of the new electrical and telephonic technologies with keen interest, chose to rename themselves: the

Telegraphers' Advocate

became the

Electric

Age,

the

Operator

renamed itself

Electrical World,

and the

Telegraphic Journal

became the

Electrical Review.

Undermined by the relentless advance of technology, the telegraphic community, along with its customs and subculture, began

to wither and decline.

What now my old telegraph,

At the top of your old tower,

As somber as an epitaph,

And as still as a boulder?

— from "Le Vieux Telegraphe," a poem by

Gustave Nadaud, translated by the author

m

orse NEVER SAW the birth of the inventions that would overshadow the telegraph. He agreed to unveil a statue of Benjamin

Franklin in Printing House Square in New York, but exposure to the bitterly cold weather on the day of the ceremony weakened

him considerably. As he lay on his sickbed a few weeks later, his doctor tapped his chest and said, "This is the way we doctors

telegraph, Professor." Morse smiled and replied, "Very good, very good." They were his last words. He died in New York on

April 2, 1872, at the age of eighty-one, and was buried in the Greenwood Cemetery. Shortly before his death, his estate had

been valued at half a million dollars—a respectable sum, though less than the fortunes amassed by the entrepreneurs who built

empires on the back of his invention. But it was more than enough for Morse, who had given freely to charity and endowed a

lectureship on "the relation of the Bible to the Sciences."

Arguably, the tradition of the gentleman amateur scientist died with him. The telegraph had originated with Morse and Cooke,

both of whom combined a sense of curiosity and invention with the single-mindedness needed to get it off the ground; it had

then entered an era of consolidation, during which scientists like Thomson and Wheatstone provided its theoretical underpinnings;

and it had ended up the province of the usual businessmen who take over whenever an industry becomes sufficiently stable,

profitable, and predictable. (Edison might appear to have much in common with Morse and Cooke on the surface, but he was no

amateur; he could never have devised the quadruplex without a keen understanding of electrical theory, something that both

Morse and Cooke lacked.)

Wheatstone died in 1875, having amassed many honors and a respectable fortune from the sale of his various telegraphic patents.

Like Morse, he was made a chevalier of the Legion of Honor, and he was knighted in 1868 following the success of the Atlantic

cable. By the time of his death, he had received enough medals to fill a box a cubic foot in capacity—and he was still not

getting on with Cooke. Wheatstone refused the offer of the Albert Medal from the Royal Society of Arts, because it was also

offered to Cooke, and Wheatstone resented the implication of equality. He continued to work as a scientist, with particular

interest in optics, acoustics, and electricity, and he died a rich and well-respected man. Alongside his innovations in the

held of telegraphy, he invented the stereoscope and the concertina, though today his name is known to students via the Wheatstone

bridge, a method of determining electrical resistance that, somewhat characteristically, he did not actually invent but helped

to popularize.

Cooke, on the other hand, failed to distinguish himself after his promising start; indeed, it's not hard to see why Wheatstone

so resented being compared to him. He worked as an official of the Electrical Telegraph Company from its establishment in

1845 until it was taken into state control by the Rritish government in 1869, when he was knighted. But he was soon in financial

difficulties. He bought a quarry and poured the money he obtained from the sale of his share of the telegraph patent into

a handful of abortive new inventions, including stone- and slate-cutting machines, and a design for a rope-hauled railway

with remote-controlled doors that he unsuccessfully tried to have adopted on the underground railway in London. The prime

minister, William Gladstone, was alerted to his plight and granted him a £100 annual state pension, the maximum possible amount.

But it was not enough to keep Cooke out of debt. His rivalry with Wheatstone continued until Wheatstone's death; Cooke attended

his funeral and was, curiously, far more accurate in his recollection of Wheatstone's role in the invention of the telegraph

thereafter. He died in 1879, having squandered his fortune.

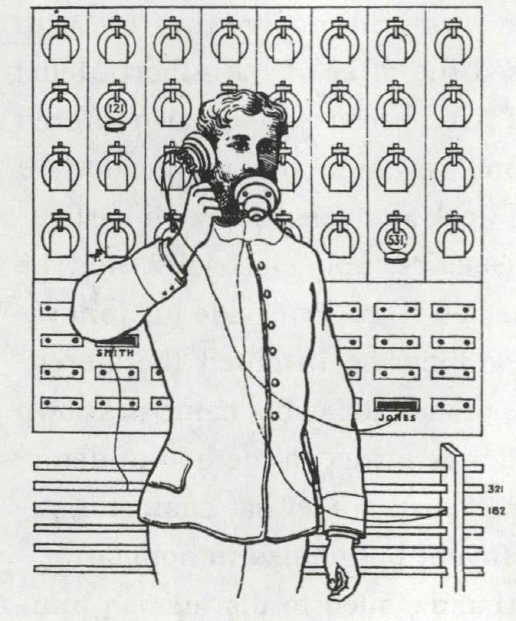

An early telephone exchange.

By the late 1880s, the telephone was booming. In 1886, ten years after its invention, there were over a quarter of a million

telephones in use worldwide. Early technological hurdles such as low sound quality, long-distance calling, and the design

of efficient manual and automatic telephone exchanges were rapidly overcome by Edison, Hughes, Watson, and others, and by

the turn of the century there were nearly 2 million phones in use. (Bell did little to improve his invention; once its success

was assured, he turned his attention to aviation instead.)

When Queen Victoria's reign ended in 1901, the telegraph's greatest days were behind it. There was a telephone in one in ten

homes in the United States, and it was being swiftly adopted all over the country. In 1903, the English inventor Donald Murray

combined the best features of the Wheatstone and Baudot automatic telegraph systems into a single machine, which, with the

addition of a typewriter keyboard, soon evolved into the teleprinter. Like the telephone, it could be operated by anyone.

The heyday of the telegrapher as a highly paid, highly skilled information worker was over; telegraphers' brief tenure as

members of an elite community with mastery over a miraculous, cutting-edge technology had come to an end. As the twentieth

century dawned, the telegraph's inventors had died, its community had crumbled, and its golden age had ended.

a

LTHOUGH IT Has now faded from view, the telegraph lives on within the communications technologies that have subsequently

built upon its foundations: the telephone, the fax machine, and, more recently, the Internet. And, ironically, it is the Internet—despite

being regarded as a quintessentially modern means of communication—that has the most in common with its telegraphic ancestor.

Like the telegraph network, the Internet allows people to communicate across great distances using interconnected networks.

(Indeed, the generic term

internet

simply means a group of interconnected networks.) Common rules and protocols enable any sort of computer to exchange messages

with any other—just as messages could easily be passed from one kind of telegraph apparatus (a Morse printer, say) to another

(a pneumatic tube). The journey of an e-mail message, as it hops from mail server to mail server toward its destination, mirrors

the passage of a telegram from one telegraph office to the next.

There are even echoes of the earliest, most primitive telegraphs—such as the optical system invented by Chappe—in today's

modems and network hardware. Every time two computers exchange an eight-digit binary number, or byte, they are going through

the same motions as an eight-panel shutter telegraph would have done two hundred years ago. Instead of using a codebook to

relate each combination to a different word, today's computers use another agreed-upon protocol to transmit individual letters.

This scheme, called ASCII (for American Standard Code for Information Interchange), says, for example, that a capital "A"

should be represented by the pattern oioooooi; but in essence the principles are unchanged since the late eighteenth century.

Similarly, Chappe's system had special codes to increase or reduce the rate of transmission, or to request that garbled information

be sent again—all of which are features of modems today. The protocols used by modems are decided on by the ITU, the organization

founded in 1865 to regulate international telegraphy. The initials now stand for International Telecommunication Union, rather

than International Telegraph Union.

More striking still are the parallels between the social impact of the telegraph and that of the Internet. Public reaction

to the new technologies was, in both cases, a confused mixture of hype and skepticism. Just as many Victorians believed the

telegraph would eliminate misunderstanding between nations and usher in a new era of world peace, an avalanche of media coverage

has lauded the Internet as a powerful new medium that will transform and improve our lives.

Some of these claims sound oddly familiar. In his 1997 book

What Will Be: How the New World of Information

Will Change Our Lives,

Michael Dertouzos of the Laboratory for Computer Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology wrote of the prospect

of "computer-aided peace" made possible by digital networks like the Internet. "A common bond reached through electronic proximity

may help stave off future flareups of ethnic hatred and national breakups," he suggested. In a conference speech in November

1997, Nicholas Negroponte, head of the MIT Media Laboratory, explicitly declared that the Internet would break down national

borders and lead to world peace. In the future, he claimed, children "are not going to know what nationalism is."

The similarities do not end there. Scam artists found crooked ways to make money by manipulating the transmission of stock

prices and the results of horse races using the telegraph; their twentieth-century counterparts have used the Internet to

set up fake "shop fronts" purporting to be legitimate providers of financial services, before disappearing with the money

handed over by would-be investors; hackers have broken into improperly secured computers and made off with lists of credit

card numbers.

People who were worried about inadequate security on the telegraph network, and now on the Internet, turned to the same solution:

secret codes. Today software to compress foles and encrypt messages before sending them across the Internet is as widely used

as the commercial codes that flourished on the telegraph network. And just as the ITU placed restrictions on the use of telegraphic

ciphers, many governments today are trying to do the same with computer cryptography, by imposing limits on the complexity

of the encryption available to Internet users. (The ITU, it should be noted, proved unable to enforce its rules restricting

the types of code words that could be used in telegrams, and eventually abandoned them.)

On a simpler level, both the telegraph and the Internet have given rise to their own jargon and abbreviations. Rather than

plugs, boomers, or bonus men, Internet users are variously known as surfers, netheads, or net izens. Personal signatures,

used by both telegraphers and Internet users, are known in both cases as sigs.

Another parallel is the eternal enmity between new, inexperienced users and experienced old hands. Highly skilled telegraphers

in city offices would lose their temper when forced to deal with hopelessly inept operators in remote villages; the same phenomenon

was widespread on the Internet when the masses hrst surged on-line in the early 1990s, unaware of customs and traditions that

had held sway on the Internet for years and capable of what, to experienced users, seemed unbelievable stupidity, gullibility,

and impoliteness.

But while conflict and rivalry both seem to come with the on-line territory, so does romance. A general fascination with the

romantic possibilities of the new technology has been a feature of both the nineteenth and twentieth centuries: On-line weddings

have taken place over both the telegraph and the Internet. In 1996, Sue Helle and Lynn Bottoms were married on-line by a minister

10 miles away in Seattle, echoing the story of Philip Reade and Clara Choate, who were married by telegraph 120 years earlier

by a minister 650 miles away. Both technologies have also been directly blamed for causing romantic problems. In 1996, a New

Jersey man filed for divorce when he discovered that his wife had been exchanging explicit e-mail with another man, a case

that was widely reported as the first example of "Internet divorce."

After a period of initial skepticism, businesses became the most enthusiastic adopters of the telegraph in the nineteenth

century and the Internet in the twentieth. Businesses have always been prepared to pay for premium services like private leased

lines and value-added information—provided those services can provide a competitive advantage in the marketplace. Internet

sites routinely offer stock prices and news headlines, both of which were available over a hundred years ago via stock tickers

and news wires. And just as the telegraph led to a direct increase in the pace and stress of business life, today the complaint

of information overload, blamed on the Internet, is commonplace.

The telegraph also made possible new business practices, facilitating the rise of large companies centrally controlled from

a head office. Today, the Internet once again promises to redefine the way people work, through emerging trends like teleworking

(working from a distant location, with a network connection to one's office) and virtual corporations (where there is no central

office, just a distributed group of employees who communicate over a network).

The similarities between the telegraph and the Internet—both in their technical underpinnings and their social impact—are

striking. But the story of the telegraph contains a deeper lesson. Because of its ability to link distant peoples, the telegraph

was the first technology to be seized upon as a panacea. Given its potential to change the world, the telegraph was soon being

hailed as a means of solving the world's problems. It failed to do so, of course-but we have been pinning the same hope on

other new technologies ever since.