The Vietnam Reader (3 page)

Read The Vietnam Reader Online

Authors: Stewart O'Nan

January 1973

Peace treaty reached. Cease-fire begins.

January 1974

The war between the North and South resumes without U.S. intervention.

April 1975

Saigon falls. U.S. trade embargo imposed. In neighboring Cambodia, Phnom Penh falls to Communist rebels.

January 1977

President Carter grants amnesty to draft evaders.

1977

The Khmer Rouge, the new rulers of Cambodia, attack the Vietnamese border.

1978

Vietnam invades Cambodia.

1979

Vietnam defeats the Khmer Rouge, installs a friendly government in Phnom Penh. China invades northern Vietnam but is repelled.

1982

Dedication of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

1989

Last Vietnamese troops withdraw from Cambodia.

1994

President Clinton lifts trade embargo on Vietnam.

1

Green

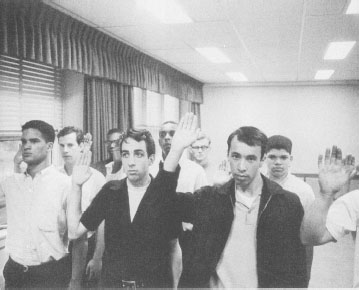

At an induction center, draftees join the U.S. Army.

These three pieces are meant to introduce the reader to the portrayal of the American soldier in Vietnam across time. Robin Moore’s

The Green Berets

appeared early in America’s involvement and cleaves to the government’s line; the soldiers are exemplary—strong, smart and heroic. O’Brien’s

If I Die in a Combat Zone

saw publication in the last year of the war, and reflects the confusion and idealism of that era. Appearing in the late seventies, O’Brien’s

Going After Cacciato

is more playful in its humor but equally damning. All three revolve around the soldier as hero and how he feels about the war.

Like the green recruit, the reader has to make sense of these conflicting views of Vietnam, learn the language, be careful of whom and what to trust. The various attitudes the authors, narrators, and characters take toward the war and how it’s being fought in these pieces seemingly can’t be reconciled. Likewise, precisely what constitutes a hero, a man, or a rational response is debatable. In their tone and focus, in their portrayal of Americans and Vietnamese, even in their charged descriptions of the settings, Moore and O’Brien appear to be covering completely different wars.

Robin Moore’s

The Green Berets

caused a sensation when it was first published in 1965. As he states in his preface, Moore, a free-lance journalist, wanted to write a nonfiction account of the U.S. Special Forces, but did such a good job of getting close to his subject that he suddenly knew too much sensitive information—so much that the

Pentagon asked for a look at the manuscript and then told Crown, his publisher, that they couldn’t release the book as it was. Moore agreed to change facts and call the book a fiction (it’s not technically a novel, more a collection of related pieces). The effect of the Pentagon’s interference (and tacit admission that Moore knew the real truth) on the book’s sales is impossible to gauge, but the hardcover was licensed by the Book of the Month Club, and the paperback climbed the bestseller list. “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” a song inspired by the book and cowritten by Moore, shot to the top of the charts. In a neat tie-in, paperbacks from 1966 bear the face of the song’s co-author and singer, Sergeant Barry Sadler.

Later, John Wayne bought the movie rights to

The Green Berets

and directed and starred in the film version. Paradoxically, Lyndon Johnson’s administration directed the Army to give Wayne whatever technical support he needed, and they did. The resulting film (1968), which Gustav Hasford ridicules in

The Short-Timers

(1979), does in fact contain a scene in which the sun sets in the east. The movie was a tremendous flop, not because Wayne was so out of vogue but because in the three years since the book had come out, mainstream American attitudes toward the war had changed.

Tim O’Brien’s

If I Die in a Combat Zone

(1973) is nonfiction. O’Brien served as an infantryman in the Army’s Americal Division in 1970-71, and his book impressionistically describes his tour of duty from when he receives his induction notice until he returns home. Sections read like fiction, however, due to O’Brien’s novelistic technique; later he would become an acclaimed literary novelist, and some reprints of

If I Die

are actually mislabeled and shelved as fiction. The book was well received by critics; it was widely hailed as the best of the first prose efforts by veterans to describe the GI’s life in Vietnam. The piece included in this section details O’Brien’s indecisiveness in the face of his induction, a subject he addressed again nearly twenty years later in the award-winning short story “On the Rainy River” in

The Things They Carried.

In 1978, O’Brien’s second novel, Going

After Cacciato,

established him as a major American writer. The book is a heavily sectioned metafiction. One narrative line follows Paul Berlin (a riff on Paul

Baumer from

All Quiet on the Western Front,

and also a reference to the Allies’ final destination in World War II) and his squadmates as they chase a fellow grunt, Cacciato, across Asia and Europe. Cacciato (in Italian, the hunter or hunted) has quit the war and is walking to Paris. A second narrative line recounts the everyday boredom and terror of the war. The time scheme is jumbled (the war scenes jumping all over the place, the road to Paris linear), and the storylines speak to each other metaphorically without becoming obvious or heavy-handed. The two narratives are mediated by sections in which Paul Berlin is keeping a lonely watch in a tower; he may be dreaming the Cacciato story to temporarily escape the present. The novel is at once frightening and hilarious, as O’Brien leavens the tragedy of the war with zany plot twists and slapstick humor. Critics were amazed by his mix of the real and the fantastic and gave Going

After Cacciato

the National Book Award. The section that appears here shows Paul Berlin during his first few days in-country. It’s typical O’Brien, a combination of realism and telling metaphor.

The Green Berets

R

OBIN

M

OORE

1965

The Green Berets

is a book of truth. I planned and researched it originally to be an account presenting, through a series of actual incidents, an inside informed view of the almost unknown marvelous undercover work of our Special Forces in Vietnam and countries around the world. It was to be a factual book based on personal experience, firsthand knowledge and observation, naming persons and places. But it turned out that there were major obstacles and disadvantages in this straight reportorial method. And so, for the variety of reasons mentioned below, I decided I could present the truth better and more accurately in the form of fiction.

You will find in these pages many things that you will find hard to believe. Believe them. They happened this way. I changed details and names, but I did not change the basic truth. I could not tell the basic truth without changing the details and the names. Here’s why.

Many of the stories incorporate a number of events which if reported merely in isolation would fail to give the full meaning and background of the war in Vietnam. Saigon’s elite press corps, and such excellent feature writers as Jim Lucas of Scripps-Howard, Jack Langguth of

The New York Times,

and Dickey Chappell of

The Reader’s Digest

have reported the detailed incidents in the war. I felt that my job in this book was to give the broad overall picture of how Special Forces men operate, so each story basically is representative of

a different facet of Special Forces action in wars like the one in Vietnam.

Also, as will be seen, Special Forces operations are, at times, highly unconventional. To report such occurrences factually, giving names, dates, and locations, could only embarrass U.S. planners in Vietnam and might even jeopardize the careers of invaluable officers. Time and again, I promised harried and heroic Special Forces men that their confidences were “off the record.” To show the kind of men they are, to present an honest, comprehensive, and informed picture of their activities, one must get to know them as no writer could who was bound to report exactly what he saw and heard.

Moreover, I was in the unique—and enviable—position of having official aid and assistance without being bound by official restrictions. Even though I always made it clear I was in Vietnam in an unofficial capacity, under these auspices much was shown and told to me. I did not want to pull punches; at the same time I felt it wasn’t right to abuse those special privileges and confidences by doing a straight reporting job.

The civic action portion of Special Forces operations can and should be reported factually. However, this book is more concerned with special missions, and I saw too many things that weren’t for my eyes—or any eyes other than the participants’ themselves—and assisted in too much imaginative circumvention of constricting ground rules merely to report what I saw under a thin disguise. The same blend of fact and “fiction” will be found in the locations in the book, many of which can be found on any map, while others are purely the author’s invention.

So for these reasons

The Green Berets

is presented as a work of fiction.

1

THE GREEN BERET — ALL THE WAY

The headquarters of Special Forces Detachment B-520 in one of Vietnam’s most active war zones looks exactly like a fort out of the old West. Although the B detachments are strictly support and administrative units for the Special Forces A teams fighting the Communist Viet Cong guerrillas in the jungles and rice paddies, this headquarters had been attacked twice in the last year by Viet Cong and both times had sustained casualties.

I was finally keeping my promise to visit the headquarters of Major (since his arrival in Vietnam, Lieutenant Colonel) Train. I deposited my combat pack in the orderly room and strode through the open door into the CO’s office.

“Congratulations, Colonel.”

Lieutenant Colonel Train, looking both youthful and weathered, smiled self-assuredly, blew a long stream of cigar smoke across his desk, and motioned for me to sit down.

Major Fenz, the operations officer, walked into the office abruptly. “Sorry to interrupt, sir. We just received word that another patrol out of Phan Chau ran into an ambush. We lost four friendlies KIA.”

I sat up straight. “Old Kornie is getting himself some action.”

Train frowned thoughtfully. “Third time in a week he’s taken casualties.”

He drummed his fingertips on the top of his desk. “Any enemy KIA, or captured weapons?”

“No weapons captured. They think they killed several VC from blood found on the foliage. No bodies.”

“I worry about Kornie,” Train said, with a trace of petulance. “He’s somehow managed to get two Vietnamese camp commanders relieved in the four months he’s been here. The new one is just what he wants, pliable. Kornie runs the camp as he pleases.”

“Kornie has killed more VC than any other A team in the three weeks since we’ve taken over here,” Fenz pointed out.

“Kornie is too damned independent and unorthodox,” Train said.

“That’s what they taught us at Bragg, Colonel,” I put in. “Or did I spend three months misunderstanding the message?”

“There are limits. I don’t agree with all the School teaches.”

“By the way, Colonel,” I said before we could disagree openly, “one reason I came down here was to get out to Phan Chau and watch Kornie in action.”

Train stared at me a moment. Then he said, “Let’s have a cup of coffee. Join us, Fenz?”

We walked out of the administration offices, across the parade ground and volleyball court of the B-team headquarters, and entered the club which served as morning coffeehouse, reading and relaxing room, and evening bar. Train called to the pretty Vietnamese waitress to bring us coffee.

There were a number of Special Forces officers and sergeants lounging around. It was to the B team that the A-team field men came on their way to a rest and rehabilitation leave in Saigon. Later they returned to the B team to await flights back to their A teams deep in Viet Cong territory.

Lieutenant Colonel Train had been an enigma to me ever since I first met him as a major taking the guerrilla course at Fort Bragg. His background was Regular Army. In World War II he had seen two years of combat duty in the Infantry, rising to the rank of staff sergeant when the war ended. Since his high-school record had been outstanding and his Army service flawless, he received an appointment to West Point. From the Point to Japan to Korea, Train had served with distinction

as an Infantry officer, and in 1954 he applied for jump school at Fort Benning and became a paratrooper.